Gender-sensitive research funding procedures

Gender equality plans (GEPs) of research funding bodies should, on the one hand, address internal stakeholders and processes, similar to research-performing organisations (internal career development, internal decision-making and leadership, internal sexual harassment policies). On the other hand, external stakeholders and the whole funding cycle need to be addressed from a gender perspective. Allocating research grants needs to be done in a gender-sensitive and inclusive manner (read more in step 6, ‘Gender budgeting’). Research funding bodies should implement a comprehensive gender strategy covering internal and external processes.

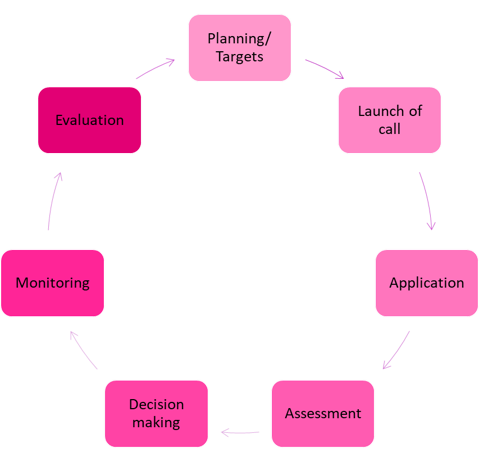

Research funding bodies can become active in all steps where (potential) applicants are addressed, reviewers and panel members are approached and guided, and applications are discussed, assessed and funded or rejected. Gender activities start when a programme or grant is designed, and all data should be analysed for a redesign of the grant programme after a call is finished.

Gendering the funding cycle

In the following text, activities promoting gender equality are discussed on the basis of a typical funding programme / grant. Following a cyclic model, gender may be relevant in the various steps of this funding cycle (see figure below), for example when funding programmes are designed, when panel members are selected or when criteria are specified. The following paragraph describes the different steps of the funding cycle and how gender equality needs to be taken into account in these steps.

Figure: Funding cycle with gender relevance

- Watch this video , in which L. Schiebinger of Stanford University discusses gendered innovations and the sex/gender dimension in research funding.

- This ‘Gender equality in the European research area community to innovate policy implementation’ (GENDERACTION) project video gives an overview of how funding agencies can contribute to the promotion of gender equality in R & I.

- A practical guide for research evaluators with six steps for a more holistic approach is provided by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (Fonds National de la Recherche (FNR)) and DORA in this video and the associated document.

- The project ‘Supporting the promotion of equality in research and academia’ (SUPERA) provides three webinars concerning gender equality in research funding bodies. The first webinar is about the GEP of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia as a research funding body and about a practical experience of gender mainstreaming in research funding. The second webinar deals with gender bias and ways for research funding bodies to combat it. The third webinar presents two experiences with gender equality policies and measures regarding funding research in Spain.

- This video from the Royal Society gives a short general introduction to unconscious bias.

- The European Research Council shows this video before remote assessments and panel meetings. It contains a step-by-step explanation about where recruitment bias can occur in research institutions.

- An Irish research body has produced the following two videos on assessment practices: ‘What happens before a panel meeting?’ and ‘What happens at a panel meeting?’

Awareness-raising

- Various funding bodies collaborated in the ‘Funding organisations for gender equality’ (FORGEN) project, a community of practice within the EU-funded project ACT, to further develop gender in research funding. Project outcomes can be found here.

- How funding bodies can shape an inclusive and gender-fair research system is discussed in a policy brief of the GENDERACTION project.

- This ‘Gender equality in engineering through communication and commitment’ (GEECCO) project report provides general instructions for funding bodies in the section on dos and don’ts for research funding organisations (pp. 34–38). You can find insights and experiences gained by research funding organisations when integrating gender equality issues into their organisations at different stages.

- A reading list containing further information for research funding organisations was made available by the SUPERA project.

- The GEP of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (in Italian) shows what a GEP for research funding organisations could look like and what measures it may contain.

- NWO developed a comprehensive approach to avoiding unconscious bias and making the picture of the ideal scientist more inclusive. Science Europe’s Practical guide to improving gender equality in research organisations provides guidance on how to avoid unconscious bias in the peer-review process, how to monitor gender equality and how to improve grant management practices.

- Supporting Women in Research – Policies, programs and initiatives undertaken by public research funding agencies published by the Global Research Council, is a collection of concrete gender measures implemented by funders from all parts of the world, embedded in different national and cultural contexts and starting from very different levels of gender awareness. The action fields cover policy frameworks and awareness-raising, sex-disaggregated data collection and analysis, ‘research opportunity’ instead of ‘track record only’, equality and diversity training, addressing institutional barriers, integrating the sex/gender dimension into research, family-friendly policies and monitoring practices on a periodic basis.

- Information about gender in research funding in general, and about challenges of and recommendations for improving transparency, can be found in this report by the Gender and Excellence Expert Group.

- SUPERA developed a tool that collects relevant resources and examples of measures that research funding bodies can use to promote gender equality during the typical cycle of a call for proposals.

- This policy brief from the GENDERACTION project lists gender equality measures and recommendations specific to research funding bodies and presents projects by research funding bodies that are considered good practices.

- This GEECCO report summarises best-practice examples of the implementation of gender equality measures in research funding bodies regarding gender mainstreaming.

- To encourage more women applicants, see the findings from EU-funded projects that have been reviewing their communication channels and the way that calls are worded and structured. The GEECCO project has compiled a List of Principles of Communication of Gender Criteria.

Capacity building

- The DFG has provided a training module for members of the head office. The first training session included lectures on stereotypes and implicit bias, among other topics. In a subsequent workshop, these aspects were further discussed in relation to the practical aspects of the evaluation and decision-making processes at the DFG.

- Instructions for how to avoid gender stereotypes in language use can be found in this guideline produced by SUPERA.

- Experiences of practitioners in implementing gender equality elements in funding instruments were published in the article ‘Practitioners’ perspectives: a funder’s experience of addressing gender balance in its portfolio of awards’.

- Best-practice examples of gender equality measures in funding bodies (not GEPs) have been provided by GEECCO.

Gender equality in the evaluation process

- DORA collected good practices and position papers from various funding bodies on methods for assessing research careers.

- The gender sector of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Research and Innovation organised a workshop en titled ‘Implicit gender biases during evaluations: how to raise awareness and change attitudes?’ It helped participants to understand what implicit/unconscious gender biases are, how they come up in evaluative processes and how they can be addressed within Horizon 2020. You can read the report of the workshop here.

- The recommendations presented by Science Europe in this position paper provide a framework on which research funding bodies can base their assessment processes and work together to reduce the increasing burden on the system and address the challenges.

- This guideline published by the project GEECCO supports staff of research funding organisations and reviewers of research proposals in promoting gender equality in the evaluation process. On the one hand, the guideline offers various recommendations concerning activities that strengthen gender balance among peer reviewers and members of committees and boards involved in the evaluation. On the other hand, it provides guidance on increasing gender sensitivity and diversity awareness in the evaluation of research proposals. This addresses the elimination of unconscious gender and other biases, the consideration of career breaks and the revision of common research-performing indicators.

- This report from the GEECCO project gives an overview of gender criteria for funding programmes and assesses them. It describes possible gender-specific criteria that can be applied by research funding bodies at different levels and also includes a selection of existing criteria already implemented by research funding bodies of different types.

- The Federation of Finnish Learned Societies produced guidelines to improve the assessment of researchers in Finland. The report provides a set of general principles that apply throughout recommended good practices.

- The paper ‘A review of barriers women face in research funding processes in the UK’ critically examines barriers and biases women are faced with when applying for research funding in the United Kingdom. Various barriers were identified and were subdivided into institutional (e.g. lack of support) and systematic barriers (e.g. maternity leave or requirement to travel), which are explained in this review.

Research assessment

- The Guideline for jury members, reviewers and research funding organisations’ employees by GEECCO provides recommendations on fostering gender equality in the evaluation process for research funding organisations’ employees and evaluators of research proposals (peer reviewers and members of evaluation committees and panels).

- GEECCO also published a report entitled Overview and assessment of gender criteria for funding programmes.

- Information on and useful recommendations for communication activities can be found in the List of Principles of Communication of Gender Criteria, published by GEECCO.

Sex/gender dimension in research

- The DFG explains the relevance of sex, gender and diversity in research on its website and provides examples of how these dimensions are considered in different disciplines. Moreover, it provides a checklist for identifying whether a research topic is gender-relevant.

- The EU-funded GENDER-NET project developed the integrating gender analysis into research (IGAR) tool. Special guidelines and checklists for IGAR were developed for research funding organisations, grant applicants and peer reviewers / evaluators. Useful references and examples have also been made available, along with IGAR indicators.

- Information on how research funding organisations assess the integration of gender in research content and research teams can be found in GEECCO’s Analysis of current data on gender in research and teaching, GEECCO’s Overview and assessment of gender criteria for funding programmes and the exhibition by GEECCO on integrating sex/gender dimensions in the content of R & I.

- The Manual with guidelines for assessment/evaluation of the gender dimension in research content from the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic provides support for integrating the sex/gender dimension into research goals, methodology and proposals. The guidelines are addressed to grant applicants, peer reviewers and rapporteurs.

- The report Gender-disaggregated data at the participating organisations of the Global Research Council: Results of a global survey addresses the sex/gender dimension in research in section 4, and provides information and results of a survey.

- Science Foundation Ireland provides information on how to integrate a sex/gender dimension into research in its guidance for applicants on ethical and scientific issues.

- The EU-funded GENDER-NET project published Manuals with guidelines on the integration of sex and gender analysis into research contents, recommendations for curricula development and indicators, which includes a manual dedicated to research funding organisations.

- This report from the Swedish Secretariat for Gender Research at the University of Gothenburg examines how research funding organisations work globally to promote the inclusion of the sex/gender dimension in R & I. The results of a worldwide survey among research funding organisations reveals how the research funding organisations organise their work, and presents common challenges and the consequences of different measures, priorities and decisions.

Gender equality in recruitment and career progression

- >Science Foundation Ireland has been successful in increasing the number of women award holders. Therefore, it initiated a measure that incentivises research-performing organisations to support and encourage excellent women candidates to apply for funding, since there was an opportunity to double the number of applicants the research institution could put forward with each woman applicant nominated. It summarises four types of implemented initiatives: (1) pre-award activities, (2) post-award activities, (3) changes to existing funding programmes and (4) the creation of a new funding programme.

- The strategies for effecting gender equality and institutional change (StratEGIC) toolkit provides advice on strategic interventions based on research from the programmes of institutions that have undertaken institutional transformation projects under the (US) National Science Foundation’s ADVANCE programme.

Monitoring

- The GEECCO log journal tutorial addresses needs and change processes related to monitoring the implementation of gender equality measures at research funding organisations/bodies. It is a knowledge resource for relevant quantitative indicators for monitoring progress towards gender equality objectives at research funding bodies. Besides the tutorial, GEECCO offers an Excel template.

COVID-19

- The Global Research Council has been active in providing information on how to take the COVID-19 pandemic into account in inclusive research funding. A questionnaire on how to find out what to do in your funding body can be found here. Concrete gender measures addressing COVID-19 effects on researchers are described here.

- R. Morgan and C. Wenham introduced their article ‘Putting a gender lens on COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) funded research’, published in The Lancet, at FORGEN’s workshop, which highlighted gender equality challenges in R & I funding during the pandemic.