Country information

Description

Progress on gender equality in Portugal since 2010

With 61.3 out of 100 points, Portugal ranks 16th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 6.6 points below the EU’s score. Since 2010, Portugal’s score has increased by 7.6 points. The country is progressing towards gender equality faster than other EU Member States. Its ranking has improved by four places since 2010.

Best performance

Portugal’s score is highest in the domain of health (84.6 points), although it ranks 20th in this domain. Its second highest score is in the domain of work (72.9 points), where Portugal ranks 15th.

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities are most pronounced in the domains of time (47.5 points) and power (51.1 points), in which Portugal ranks 25th and 13th, respectively.

Biggest improvement

Portugal’s scores have improved the most in the domains of power and time (+ 16.2 points and + 8.8 points, respectively, since 2010). In the domain of time, Portugal has moved up two places in the ranking.

A step backwards

Progress has stalled in the domain of health (+ 0.3 points). Portugal’s rankings have dropped by one place in the domains of work and money, in which its scores have increased by only 1.5 points and 1 point, respectively.

Key highlights

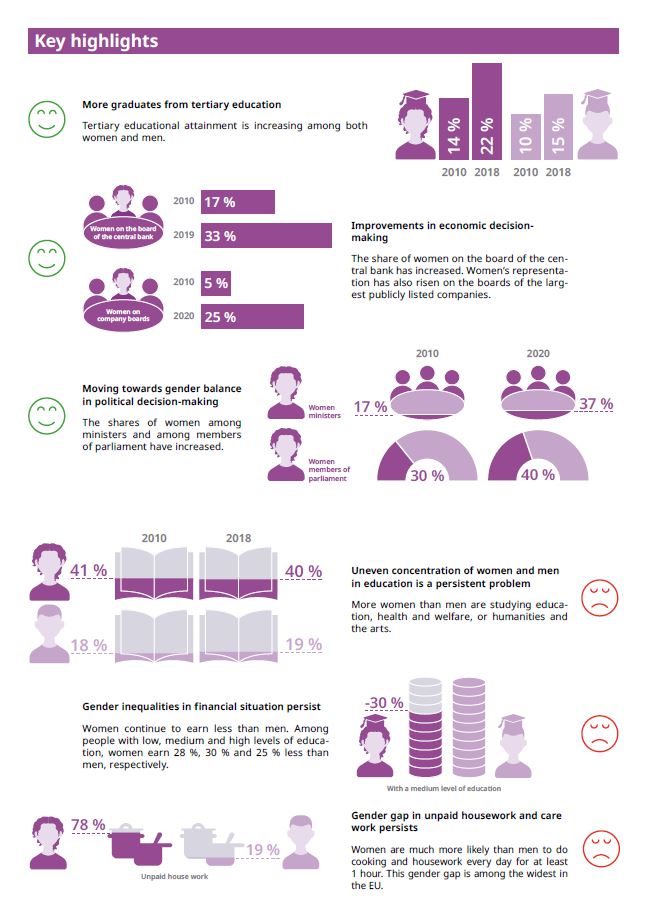

Positives

- Tertiary educational attainment is increasing among both women and men.

- The share of women on the board of the central bank has increased. Women’s representation has also risen on the boards of the largest publicly listed companies.

- The shares of women among ministers and among members of parliament have increased.

Negatives

- More women than men are studying education, health and welfare, or humanities and the arts.

- Women continue to earn less than men. Among people with low, medium and high levels of education, women earn 28 %, 30 % and 25 % less than men, respectively.

- Women are much more likely than men to do cooking and housework every day for at least 1 hour. This gender gap is among the widest in the EU.

Description

Progress in gender equality in Portugal since 2010

With 62.2 out of 100 points, Portugal ranks 15th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 5.8 points below the EU’s score. Since 2010, Portugal’s score has increased by 8.5 points and its ranking has improved by four places. Since 2018, Portugal’s score has increased by 0.9 points, mainly driven by improvements in the domains of power. Its ranking has remained the same.

Best Performance

Portugal’s ranking is the highest in the domain of health in which it scores 84.8 points. This performance is mainly driven by a high score in the sub-domain of access to health. However, Portugal only ranks 19th among all Member States, and its score is 3.0 points below the EU’s score for health.

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities are most pronounced in the domain of time (47.5 points) in which Portugal ranks 24th. Despite improvements in this domain since 2010 (+ 8.8 points), the score remains especially low in the sub-domain of social activities (35.7 points). Portugal’s ranking is the second lowest in this sub-domain.

Biggest improvement

With 53.6 points, Portugal’s score has improved the most in the domain of power (+ 18.7 points) since 2010. Its ranking has improved from the 12th to the 11th place. Since 2018, Portugal has also gained 2.5 points in the domain of power, improving its ranking by one place.

A step backwards

Since 2018, Portugal’s ranking has dropped by two places in the domain of money. In this domain, Portugal scores 8.8 points below the EU’s score and ranks 21st. Progress has stalled in the sub-domain of financial resources (earnings and income), in which Portugal’s ranking has dropped from the 18th to the 19th place.

Description

Progress in gender equality

With 62.8 out of 100 points, Portugal ranks 15th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 5.8 points below the EU’s score.

Since 2010, Portugal’s score has increased by 9.1 points, raising its ranking by four places. Since 2019, Portugal’s score has improved only marginally (+ 0.6 points), and its ranking has remained the same. This is because the improvements in the domain of money have been balanced out with a setback in the domain of health and slow progress in the domains of power and knowledge.

Best performance

Portugal’s ranking is the highest (13th among all Member States) in the domain of work in which it scores 73.4 points (+ 0.2 points since 2019 and + 2.0 points since 2010). Within this domain, the country performs best in the sub-domain of participation at work, ranking 7th with a score of 87.8 points. Since 2019, Portugal’s score in this sub-domain has dropped by 0.4 points, which may indicate an emerging area of concern.

Portugal also ranks 13th in the domain of power with a score of 55.5 points. In this domain, the country scores highest in the sub-domain of political power (64.5 points) and ranks 10th.

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities are most pronounced in the domain of time (47.5 points) in which Portugal ranks 24th. Despite improvements in this domain since 2010 (+ 8.8 points), the score remains especially low in the sub-domain of social activities (35.7 points). Portugal’s ranking is the second lowest in this sub-domain. There is much room for improvement also in the sub-domain of care activities, in which Portugal scores 63.3 points and ranks 20th among all Member States.

Biggest improvement

Since 2019, Portugal’s score has improved in the domain of money (+ 1.1 points). With a score of 74.7 points, its ranking has increased from the 21st to the 19th place. Progress in the sub-domains of economic situation (+ 1.4 points) and financial resources (+ 0.8 points) is the driver of these improvements.

Portugal’s score has also improved in the domain of power (+ 1.9 points since 2019 and 20.6 points since 2010). The most recent improvements were largely driven by an increase in the country’s score in the sub-domain of social decision-making (+ 5.2 points). However, because progress has been faster in other countries, Portugal’s ranking has dropped from the 11th to the 13th place in the domain of power since 2019.

A step backwards

Since 2019, Portugal’s ranking has dropped from the 19th to the 22nd place in the domain of health (with – 0.3 points). Higher levels of gender inequality in health behaviour (– 1.6 points) are the drivers of this change.

Key highlights

Focus 2022: COVID-19 in Portugal

-

Women were more likely to care for small children alone and for longer period of time

During the pandemic, 46 % of women compared to 28 % of men reported caring for and supervising children completely or mostly by themselves. Men were much more likely to spend 1–4 hours a day on care for their children or grandchildren aged 0–11, rather than more than 4 hours a day (72 % and 20 %, respectively). For women, the percentages were almost identical, with 47 % of women spending between 1–4 hours a day and 49 % more than 4 hours a day on caring for their children or grandchildren aged 0–11.

-

More men relied regularly on institutions for long-term care

Significantly fewer women than men relied on residential long-term care facilities or institutions (21 % and 40 %, respectively) and social workers (18 % and 33 %, respectively) for the provision of care to older people, or people with health problems or disabilities. However, very high percentages of women and men relied on relatives, neighbours or friends for external support with long-term care in Portugal (63 % of women and 59 % of men).

-

Household work fell primarily on women during the pandemic

In 2021, nearly 67 % of women compared to only 18 % of men reported carrying out household chores completely or mostly by themselves. Overall, women spent more time on household work than men, with 35 % of women and only 18 % of men spending more than four hours a day on household chores.

Description

Progressos na igualdade de género em Portugal desde 2010

Com uma pontuação de 62,2 em 100, Portugal ocupa a 15.ª posição na UE no Índice de Igualdade de Género. A sua pontuação encontra-se 5,8 pontos abaixo da média da UE.

Desde 2010, Portugal subiu 8,5 pontos na pontuação e quatro lugares na classificação. Desde 2018, a pontuação de Portugal aumentou 0,9 pontos, devido principalmente, a melhorias nos domínios do poder. A classificação manteve-se inalterada.

Melhor desempenho

A pontuação mais elevada de Portugal surge no domínio da saúde, com uma pontuação de 84,8 pontos. Este desempenho deve-se sobretudo à pontuação elevada no subdomínio do acesso à saúde. No entanto, Portugal ocupa apenas o 19.º lugar entre todos os Estados-Membros, com menos 3,0 pontos do que a pontuação da UE em matéria de saúde.

Maior margem para melhorias

As desigualdades de género são mais acentuadas no domínio do tempo (47,5 pontos), em que Portugal ocupa o 24.º lugar. Apesar das melhorias neste domínio desde 2010 (+8,8 pontos), a pontuação continua a ser especialmente baixa no subdomínio das atividades sociais (35,7 pontos). A classificação de Portugal é a segunda mais baixa neste subdomínio.

Maior melhoria

Com 53,6 pontos, a pontuação de Portugal melhorou mais no domínio do poder (+18,7 pontos) desde 2010, tendo a sua classificação passado do 12.º para o 11.º lugar. Desde 2018, Portugal ganhou também 2,5 pontos no domínio do poder, subindo um lugar na classificação.

Menor progresso

Desde 2018, a classificação de Portugal desceu dois lugares no domínio do dinheiro. Neste domínio, Portugal regista 8,8 pontos abaixo da pontuação da UE e ocupa o 21.º lugar. Houve uma estagnação do progresso no subdomínio dos recursos financeiros (salários e rendimentos), em que a classificação de Portugal caiu do 18.º para o 19.º lugar.

Description

Progresso na igualdade de género

Com uma pontuação de 62,8 em 100, Portugal ocupa a 15.ª posição na UE no Índice de Igualdade de Género. A sua pontuação encontra-se 5,8 pontos abaixo da média da UE.

Desde 2010, Portugal subiu 9,1 pontos na pontuação e quatro lugares na classificação. Desde 2019, a pontuação de Portugal melhorou ligeiramente (+ 0,6 pontos) e a sua classificação manteve-se. Isso porque as melhorias nos domínios do poder e do dinheiro foram compensadas com um retrocesso no domínio da saúde e um progresso pouco significativo nos domínios do conhecimento e do trabalho.

Melhor desempenho

A classificação de Portugal é a mais alta (13.º entre todos os Estados-Membros) no domínio do trabalho, com uma pontuação de 73,4 pontos (+ 0,2 pontos desde 2019 e + 2,0 pontos desde 2010). Neste domínio, o país tem o melhor desempenho no subdomínio da participação no trabalho, classificando-se em 7.º lugar com uma pontuação de 87,8 pontos. Desde 2019, a pontuação de Portugal neste subdomínio caiu 0,4 pontos, o que pode indicar uma área emergente de preocupação.

Portugal ocupa também a 13.ª posição no domínio do poder, com uma pontuação de 55,5 pontos. Neste domínio, o país regista a pontuação mais elevada no subdomínio do poder político (64,5 pontos) e ocupa o 10.º lugar.

Maior margem para melhorias

As desigualdades de género são mais acentuadas no domínio do tempo (47,5 pontos), em que Portugal ocupa o 24.º lugar. Apesar das melhorias neste domínio desde 2010 (+8,8 pontos), a pontuação continua a ser especialmente baixa no subdomínio das atividades sociais (35,7 pontos). A classificação de Portugal é a segunda mais baixa neste subdomínio. Há muito a melhorar também no subdomínio das atividades de prestação de cuidados, onde Portugal regista 63,3 pontos e ocupa o 20.º lugar entre todos os Estados-Membros.

Maior melhoria

Desde 2019, a classificação de Portugal melhorou no domínio do dinheiro (+ 1,1 pontos). Com uma pontuação de 74,7 pontos, subiu na classificação da 21.ª para a 19.ª posição. O progresso nos subdomínios da situação económica (+ 1,4 pontos) e dos recursos financeiros (+ 0,8 pontos) é o motor dessas melhorias.

A pontuação de Portugal também melhorou no domínio do poder (+ 1,9 pontos desde 2019 e 20,6 pontos desde 2010). As melhorias mais recentes foram em grande parte impulsionadas por um aumento da pontuação do país no subdomínio da tomada de decisões sociais (+ 5,2 pontos). No entanto, como o progresso tem sido mais rápido noutros países, a classificação de Portugal caiu do 11.º para o 13.º lugar no domínio do poder, desde 2019.

Um passo atrás

Desde 2019, a classificação de Portugal caiu do 19.º para o 22.º lugar no domínio da saúde (com - 0,3 pontos). Os níveis mais elevados de desigualdade de género no comportamento em matéria de saúde (- 1,6 pontos) são os motores desta mudança.

Key highlights

Principais destaques

-

Mulheres mais suscetíveis de cuidar de crianças pequenas sozinhas e por um período de tempo mais longo

Durante a pandemia, 46 % das mulheres, em comparação com 28 % dos homens, declararam cuidar e supervisionar crianças sobretudo ou completamente sozinhas. Era bastante mais provável que os homens passassem 1-4 horas por dia a cuidar dos filhos ou netos com idades entre os 0 e os 11 anos do que mais de 4 horas por dia (72 % e 20 %, respetivamente). Para as mulheres, as percentagens foram quase idênticas, com 47 % das mulheres a passar entre 1-4 horas por dia e 49 % mais de 4 horas por dia a cuidar dos filhos ou netos com idades entre os 0 e os 11 anos.

-

Mais homens dependiam com regularidade de instituições para os cuidados de longa duração

Um número significativamente inferior de mulheres, em comparação aos homens, dependia de instalações ou instituições residenciais de cuidados de longa duração (21 % e 40 %, respetivamente) e de assistentes sociais (18 % e 33 %, respetivamente) para a prestação de cuidados a pessoas idosas ou a pessoas com problemas de saúde ou incapacidades. No entanto, percentagens muito elevadas de mulheres e homens dependiam de familiares, vizinhos ou amigos para apoio externo com cuidados de longa duração em Portugal (63 % das mulheres e 59 % dos homens).

-

O trabalho doméstico recaiu principalmente sobre as mulheres durante a pandemia

Em 2021, quase 67 % das mulheres, em comparação com apenas 18 % dos homens, declararam realizar as tarefas domésticas sobretudo ou completamente sozinhas. Em geral, as mulheres dedicavam mais tempo às tarefas domésticas do que os homens, com 35% de mulheres e apenas 18 % de homens a dedicar mais de 4 horas por dia às tarefas domésticas.

Description

Progress in gender equality

With 67.4 points out of 100, Portugal ranks 15th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 2.8 points below the score for the EU as a whole.1

Since 2010, Portugal’s score has increased by 13.7 points, mainly due to improvements in the domains of time (+ 29.1 points) and power (+ 22.5 points). Since 2020, Portugal’s score has increased by 4.6 points, which is one of the biggest improvements among the Member States for this period. This can be attributed to improvements in the domains of time (+ 20.3 points) and work (+ 3.1 points). Portugal has maintained the same position as in 2020, ranking 15th in the Index.

Best performance

Portugal’s highest ranking (9th out of all Member States) is in the domain of work, in which it scores 76.5 points. Portugal’s score in this domain has increased by 3.1 points since 2020, and its ranking has risen by four places. Within this domain, the country performs best in the sub-domain of participation (90.0 points), where it ranks 5th in the EU. This is Portugal’s highest ranking across all sub-domains, with an improvement of two places since 2020.

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities in Portugal are strongly pronounced in the domain of health (84.1 points), in which the country ranks 23rd in the EU. Since 2010, progress in this domain has stalled (– 0.2 points), resulting in a drop in ranking from 20th place to 23rd. With a score of 85.1 points, the country has most room for improvement in the sub-domain of health status, in which it ranks 25th. In the sub-domain of health access, Portugal scores 94.6 points and ranks 24th out of all EU Member States.

Biggest improvement

Since 2020, the biggest improvement in Portugal’s score has been in the domain of time (+ 20.3 points), moving the country’s ranking up from 24th to 11th place. An improvement in the sub-domain of social activities (+ 21.6 points) has been the key driver of this change. As a result, the country’s ranking in this sub-domain has risen 15 places to 11th. In the sub-domain of care activities, Portugal scores 80.3 points and ranks 12th in the EU.

A step backwards

Since 2020, Portugal’s score has decreased slightly in the domain of money (– 1.1 points), taking the country down two places in the ranking to 21st in the EU. This change can be attributed to increasing gender inequalities in the sub-domain of economic situation (– 2.9 points), resulting in a drop in ranking for this sub-domain from 16th place to 19th. In the sub-domain of financial resources, progress has stalled since 2020, with Portugal scoring 63.3 points and ranking 19th (two places lower than in 2010).

Convergence

Upward convergence in gender equality describes increasing equality between women and men in the EU, accompanied by a decline in variations between Member States. This means that countries with lower levels of gender equality are catching up with those with the highest levels, thereby reducing disparities across the EU. Analysis of convergence patterns in the Gender Equality Index shows that disparities between Member States decreased over the period 2010–2021, and that EU countries continue their trend of upward convergence.

Looking more closely at the performance of each Member State, patterns can be identified that reflect a relative improvement or slipping back in the Gender Equality Index score of each Member State in relation to the EU average.

Portugal is catching up with other Member States. This means that its Gender Equality Index score was initially lower than the EU average, but has grown faster over time, reducing the gap.

Key highlights

Focus 2023: The European Green Deal

-

Women in Portugal tend to choose environmentally friendly options more often than men

In 2022, 56 % of women in Portugal, compared with 46 % of men, regularly avoided plastic and/or single-use products, which is higher than the EU average (49 % and 42 %, respectively). Considerably more women (58 %) than men (48 %) regularly reported choosing environmentally friendly options in childcare activities. Around 34 % of women reported regularly avoiding animal products, compared with 27 % of men.

-

Even before the current energy crisis, single women were struggling

In 2021, 8 % of single women in Poland, compared with 7 % of single men, were unable to adequately heat their homes. The gender gap was most pronounced among lone parents, with 6 % of lone mothers reporting that they were unable to keep their homes warm, compared with 2 % of lone fathers. Similarly, 6 % of lone mothers and 2 % of lone fathers reported being in arrears on their utility bills in 2021. These figures are likely to have risen significantly with the ongoing energy crisis.

-

Women were highly underrepresented in the EU energy and transport sectors in Portugal, and in decision-making

There are notably fewer women than men working in the transport and energy sectors in Portugal. In 2022, only 34 % of workers in the energy sector were women.2 Similarly, women accounted for just 20 % of workers in the transport sector in 2022. Women are also considerably underrepresented in some decision-making roles. In 2022, only 26 % of decision-makers in parliamentary committees focusing on the environment and climate change were women. Conversely, however, 80 % of senior administrators in national ministries dealing with the environment and climate change were women.

Description

Progresso na igualdade de género

Com uma pontuação de 67,4 em 100, Portugal ocupa a 15.ª posição na UE no Índice de Igualdade de Género. A pontuação está 2,8 pontos abaixo da pontuação para a UE no seu conjunto.1

Desde 2010, a pontuação de Portugal aumentou 13,7 pontos, principalmente devido a melhorias nos domínios do tempo (+ 29,1 pontos) e do poder (+ 22,5 pontos). Desde 2020, a pontuação de Portugal aumentou 4,6 pontos, o que constitui uma das maiores melhorias entre os Estados-Membros neste período. Este facto pode ser atribuído a melhorias nos domínios do tempo (+ 20,3 pontos) e do trabalho (+ 3,1 pontos). Portugal manteve a mesma posição que em 2020, ocupando o 15.º lugar no Índice.

Melhor desempenho

A classificação mais elevada de Portugal (9.º lugar entre todos os Estados-Membros) situa-se no domínio do trabalho, com uma pontuação de 76,5 pontos. A pontuação de Portugal neste domínio aumentou 3,1 pontos desde 2020 e a sua classificação subiu quatro lugares. Neste domínio, o país apresenta o melhor desempenho no subdomínio da participação (90,0 pontos), ocupando o 5.º lugar na UE. Esta é a classificação mais elevada de Portugal em todos os subdomínios, com uma melhoria de dois lugares desde 2020.

Maior margem para melhorias

As desigualdades entre homens e mulheres em Portugal são muito acentuadas no domínio da saúde (84,1 pontos), em que o país ocupa o 23.º lugar na UE. Desde 2010, os progressos neste domínio estagnaram ( -0,2 pontos), resultando numa descida na classificação do 20.º lugar para o 23.º lugar. Com uma pontuação de 85,1 pontos, o país tem maior margem para melhorias no subdomínio do estado de saúde, em que ocupa o 25.º lugar. No subdomínio do acesso à saúde, Portugal obtém 94,6 pontos e ocupa o 24.º lugar entre todos os Estados-Membros da UE.

Maior melhoria

Desde 2020, a maior melhoria na pontuação de Portugal registou-se no domínio do tempo (+ 20,3 pontos), resultando numa subida da classificação do país, do 24.º para o 11.º lugar. A melhoria no subdomínio das atividades sociais (+ 21,6 pontos) tem sido o principal motor desta mudança. Em consequência, a classificação do país neste subdomínio subiu 15 lugares, passando a ocupar a 11.ª posição. No subdomínio das atividades de prestação de cuidados, Portugal obteve uma pontuação de 80,3 pontos e ocupa o 12.º lugar na UE.

Um passo atrás

Desde 2020, a pontuação de Portugal diminuiu ligeiramente no domínio monetário (-1,1 pontos), fazendo com que o país descesse dois lugares na classificação, para a 21.º posição. Esta mudança pode ser atribuída ao aumento das desigualdades de género no subdomínio da situação económica (-2,9 pontos), resultando numa queda na classificação deste subdomínio do 16.º para o 19.º lugar. No subdomínio dos recursos financeiros, os progressos estagnaram desde 2020, com Portugal a obter 63,3 pontos e a ocupar a 19.ª posição (menos dois lugares do que em 2010).

Convergência

A convergência ascendente na igualdade de género descreve o aumento da igualdade entre homens e mulheres na UE, acompanhado por um declínio das variações entre os Estados-Membros. Isto significa que os países com níveis mais baixos de igualdade de género estão a aproximar-se dos países com os níveis mais elevados, reduzindo assim as disparidades na UE. A análise dos padrões de convergência no Índice de Igualdade de Género mostra que as disparidades entre os Estados-Membros diminuíram durante o período 2010-2021 e que os países da UE continuam a sua tendência de convergência ascendente.

Analisando mais atentamente o desempenho de cada Estado-Membro, é possível identificar padrões que refletem uma melhoria relativa ou um retrocesso na pontuação do Índice de Igualdade de Género de cada Estado-Membro em relação à média da UE.

Portugal está a recuperar o atraso em relação aos outros Estados-Membros. Isto significa que a sua pontuação no Índice de Igualdade de Género foi inicialmente inferior à média da UE, mas subiu mais rapidamente ao longo do tempo, reduzindo as disparidades.

Key highlights

Principais destaques

-

As mulheres em Portugal tendem a escolher opções ecológicas com mais frequência do que os homens

Em 2022, 56 % das mulheres em Portugal, em comparação com 46 % dos homens, evitaram regularmente produtos de plástico e/ou utilização única, o que é superior à média da UE (49 % e 42 %, respetivamente). Muito mais mulheres (58 %) do que homens (48 %) comunicaram regularmente escolher opções amigas do ambiente nas atividades de cuidado de crianças. Cerca de 34 % das mulheres declararam evitar regularmente produtos de origem animal, em comparação com 27 % dos homens.

-

Mesmo antes da atual crise energética, as mulheres solteiras enfrentavam dificuldades

Mesmo antes do impacto total da atual crise energética, muitas pessoas tinham dificuldades em pagar a energia e o aquecimento. Em Portugal, as disparidades entre os géneros eram mais acentuadas entre as famílias monoparentais, sendo as mulheres as mais desfavorecidas. Em 2021, 27 % das mulheres solteiras não conseguiam manter as suas casas adequadamente aquecidas, em comparação com 19 % dos homens solteiros. Problema semelhante foi relatado por migrantes de países terceiros, com 19 % de mulheres migrantes de países terceiros e 17 % de homens migrantes de países terceiros a terem dificuldade em manter as suas casas aquecidas. É provável que estes valores tenham aumentado significativamente com a atual crise energética.

-

As mulheres estavam fortemente sub-representadas nos setores da energia e dos transportes da UE em Portugal e na tomada de decisões

Em Portugal, há muito menos mulheres do que homens a trabalhar nos setores dos transportes e da energia. Em 2022, apenas 34 % dos trabalhadores do setor da energia eram mulheres.2 Do mesmo modo, em 2022, as mulheres representavam apenas 20 % dos trabalhadores no setor dos transportes. As mulheres também estão consideravelmente sub-representadas em alguns papéis de tomada de decisão. Em 2022, apenas 26 % dos decisores nas comissões parlamentares dedicadas ao ambiente e às alterações climáticas eram mulheres. Em contrapartida, no entanto, 80 % dos administradores superiores dos ministérios nacionais que lidam com o ambiente e as alterações climáticas eram mulheres.

Domain information

Description

The domain of work score has slightly increased due to some progress in both sub-domains: participation and segregation and quality of work.

The employment rates (20-64) for women and men (66 % and 73 %, respectively) have not yet reached Portugal’s Europe 2020 strategy (EU2020) target, which is to have 75 % of the adult population in employment.

For both women and men, the employment rate decreases when the number of hours worked is taken into account. The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate of women is 44 %, compared to 53 % for men.

The gender gap in employment, measured by FTE employment rates, has narrowed slightly, while the duration of working life has increased slightly for women and remained stable for men.

Among women and men in couples with children, the FTE employment rate for women is 72 %, compared to 80 % for men. Among highly educated women and men, the gender gap is smaller compared to the gender gap among women and men with middle and low levels of education.

14 % of women work part-time, compared to 11 % of men. On average, women work 38 hours per week, compared to 41 hours per week for men. 3 % of working-age women versus 0.1 % of working-age men either outside the labour market or work part-time due to care responsibilities.

The sub-domain of segregation and quality of work has improved. The gender-segregated labour market remains a reality for both women and men. Approximately three times more women than men work in education, human health and social work activities (EHW) (28 % of women, compared to 7 % of men). Three times more men (30 %) than women (9 %) work in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations.

Description

The situation of gender equality in the domain of money shows some progress, with gains in financial resources, and some signs of improvements in the economic situation sub-domain.

Mean monthly earnings of women and men have increased, but women continue to earn less (roughly 16 % less than men every month). The gap is bigger among highly educated people, lone parents and women and men in couples with children, always to the detriment of women.

The population of women and men at risk of poverty has remained the same, and they are at a similar risk of poverty (about 19 % and 18 %, respectively).

Women and men living in Portugal born outside the EU are considerably more at risk of poverty, with 38 % of women and 40 % of men in these groups at risk of poverty.

Other groups at high risk of poverty are lone mothers (35 %) and young women and men (25 % of women and 28 % of men aged 15-24).

Inequalities between the richest and the poorest decreased slightly, especially among women.

The gender pay gap is 18 % to the detriment of women, two percentage points (p.p.) above the EU-28 average. In 2012, women had lower pensions than men and the gender gap was 31 % (38 % in the EU-28).

Description

The score in the domain of knowledge has improved by 6.2 points. This is the result of significant progress made in the sub-domain of attainment and participation in education.

The percentage of women with tertiary education has increased from 11 % to 20 %. The number of tertiary education graduates increased similarly among men (from 8 % to 14 %). A large gender gap thus remains: there are still more women than men holding a tertiary education degree. Only 6 % of men and 8 % of women with disabilities hold a tertiary degree.

Adult participation in lifelong learning and training — both formal and non-formal — has increased for both genders but particularly for men. 15 % of women and 16 % of men are enrolled in such activities.

Segregation of study fields remains a significant challenge, with 41 % of women students (compared to only 19 % of men students) concentrated in education, health and welfare, and humanities and arts — fields that are traditionally seen as ‘feminine’. There has been limited progress in this sub-domain.

Description

The domain of time remained stable, with the greatest challenge remaining in the division of time allocated to domestic, care and leisure activities between women and men. This score for Portugal is one of the lowest in the EU-28 (18 points below the EU-28 average).

Modest progress has been made in closing the gender gap when it comes to women and men caring for children or grandchildren. 37 % of women and 28 % of men dedicated 1 hour or more a day to caring activities.

87 % of women in a couple with children take care of their family for 1 hour or more daily, compared to 79 % of men. The gender gap is notable for those aged 25-49 (69 % of women, compared to 43 % of men).

78 % of women do cooking and housework every day for at least 1 hour, compared to only 19 % of men.

This uneven distribution of household responsibilities is the highest within the 50-64 age group, with 90 % of women and 20 % of men cooking or doing housework every day. Younger generations are displaying similar patterns of unequal sharing of housework (83 % of women aged 25-49 cook every day, compared to 21 % of men).

Inequality in time-sharing at home also extends to other social activities. Men are more likely than women to participate in sporting, cultural, and leisure activities outside the home (20 % of men, compared to 10 % of women).

Portugal has met both of the ‘Barcelona targets’, which are to have at least 33 % of children below the age of three in childcare and 90 % of children between the age of three and school age in childcare. In Portugal, the enrolment rates are 47 % and 90 %, respectively.

Description

In the domain of power, the score has increased significantly, although it remains the domain with the lowest score in Portugal. This increase was driven by gains in the sub-domains of political and economic power. The sub-domain of social power shows a slight drop in score.

In terms of women’s political representation, progress has been observed at the ministerial, parliamentarian and regional levels.

The share of women in ministerial positions increased from 14 % to 23 %, and the share of women Members of Parliament rose from 23 % to 33 %.

Despite progress seen in the representation of women on the corporate boards of the largest companies, men still represent 88 % of decision-makers in this sector.

In the finance sector, women’s representation is also progressing slowly. Women represent 6 % of members of the central bank, an improvement from having no women members in the central bank in 2005.

A third of board members of research funding organisations, a third of board members of publicly owned broadcasting organisations and only 13 % of members of the highest decision-making bodies of national Olympic sport organisations are women.

Description

Regarding health status, access to services and behaviour, women and men in Portugal (and more broadly in the EU-28) are doing relatively well, with limited gender inequalities.

The health score is still a strong score, with gender gaps in access to services narrowing, although there has been a slight setback in the score and rank for this domain. The decrease in the score is driven by a decrease in the sub-domain of access. Unmet needs for dental examination have increased for women and men.

Life expectancy has increased for both women and men. Women on average live 6 years longer than men. However, the number of years women can expect to live in good health has decreased from 57 to 55 years, while this number has remained at 58 years for men.

42 % of women and 52 % of men in Portugal rate their health as ‘good’ or ‘very good’. When taking level of education into consideration, perception of good health drops as level of education does, with only 27 % of women and 40 % of men with low levels of education declaring they are in good health.

In Portugal, 37 % of men engage in smoking and/or harmful drinking practices, compared to 15 % of women. Men are also more likely than women to engage in health-promoting behaviour, such as exercising and eating fruit and vegetables (35 % compared to 30 %).

Description

Violence against women is included in the Gender Equality Index as a satellite domain. This means that the scores of the domain of violence do not have an impact on the final score of the Gender Equality Index. From a statistical perspective, the domain of violence does not measure gaps between women and men as core domains do. Rather, it measures and analyses women’s experiences of violence. Unlike other domains, the overall objective is not to reduce the gaps of violence between women and men, but to eradicate violence completely.

A high score in the Gender Equality Index means a country is close to achieving a gender-equal society. However, in the domain of violence, the higher the score, the more serious the phenomenon of violence against women in the country is. On a scale of 1 to 100, 1 represents a situation where violence is non-existent and 100 represents a situation where violence against women is extremely common, highly severe and not disclosed. The best-performing country is therefore the one with the lowest score.

Portugal’s score for the composite measure of violence is 24.5, which is slightly lower than the EU average.

In Portugal, 24 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15. 66 % of them have experienced health consequences as a result of being subjected to at least one episode of physical and/or sexual violence since the age of 15.

18 % of women who have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by any perpetrator in the past 12 months have not told anyone. This rate is higher than that estimated at European Union level (13 %)

At the societal level, violence against women costs Portugal an estimated EUR 4.7 billion per year through lost economic output, service utilisation and personal costs (1).

The domain of violence is made up of three sub-domains: prevalence, which measures how often violence against women occurs; severity, which measures the health consequences of violence; and disclosure, which measures the reporting of violence.

[1] This is an exercise done at EU level to estimate the costs of the three major dimensions: services, lost economic output and pain and suffering of the victims. The estimates were extrapolated to the EU from a United Kingdom case study, based on population size. EIGE, Estimating the costs of gender-based violence in the European Union, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2014, p. 142.

Description

Portugal’s score in the domain of work is 72.5, showing progress of 1.9 points since 2005 (+ 0.5 points since 2015), with improvements in both sub-domains.

The employment rate (of people aged 20-64) is 72 % for women and 79 % for men. With the overall employment rate of 75 %, Portugal has achieved its national EU 2020 employment target of 75 %. The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate decreased for women (from 47 % to 45 %) and men (from 64 % to 56 %) between 2005 and 2017, narrowing the gender gap (from 17 percentage points (p.p.) to 10 p.p.). Among women and men in couples with children, the FTE employment rate is 80 % for women and 91 % for men. The gender gap decreases in proportion to increases in education level: among highly educated women and men, the gender gap is much smaller (2 p.p.), compared to women and men with low levels of education (17 p.p.).

Around 13 % of women work part-time, compared to 8 % of men. On average, women work 38 hours per week, and men work 41 hours. The uneven concentration of women and men in different sectors of the labour market is an issue: 29 % of women work in education, health and social work, compared to 7 % of men. Fewer women (9 %) than men (31 %) work in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations.

Description

Portugal’s score in the domain of money is 72.1, showing progress of 3.3 points since 2005 (+ 1.2 points since 2015), with improvements in the economic and financial situations of women and men.

With mean monthly earnings increasing less for women (+ 9 %) than for men (+ 15 %) from 2006 to 2014, the gender gap grew: women earn 16 % less than men. In couples with and without children, women earn a quarter less than men. Among women and men with low, medium and high education, women earn around a third less than men. The gap is also wider among people born outside Portugal: foreign-born women earn 32 % less than foreign-born men, compared to native-born women who earn 23 % less than native-born men.

The risk of poverty has remained the same since 2005: nearly 19 % of women and 18 % of men are at risk. People facing the highest risk of poverty are lone parents (33 %), young people aged 15-24 (26 %), single people (25 %) and people with low education (24 %). Inequalities in income distribution decreased among women and men between 2005 and 2017. Women earn, on average, around 84 cents for every euro a man makes per hour, resulting in a gender pay gap of 16 %. The gender pension gap is 32 %.

Description

Portugal’s score in the domain of knowledge is 55.1, with a 6.5-point increase since 2005 (+ 0.3 points since 2015). Portugal ranks 23rd in the domain of knowledge in the EU but has improved significantly in the sub-domain of attainment and participation.

The share of women tertiary graduates rose between 2005 and 2017 (from 11 % to 21 %). For men, increases in tertiary attainment have progressed at a slower pace (from 8 % to 15 %). The gender gap in attainment is wider for women and men born outside Portugal in the EU (16 p.p.) and between women and men aged 25-49 (13 p.p.). Portugal has not yet reached its national EU 2020 target of having 40 % of people aged 30-34 obtain tertiary education. The current rate is 34 % (43 % for women and 24 % for men). Participation in lifelong learning increased for both women and men from 11 % to 15 % for women and 16 % for men between 2005 and 2017.

The uneven concentration of women and men in tertiary study fields remains a challenge for Portugal. About 40 % of women students and 18 % of men students study education, health and welfare, or humanities and art.

Description

Portugal’s score in the domain of time has not changed since the last edition of the Index, because new data is not available. The next data update for this domain is expected in 2021. More frequent time-use data would help to track progress in this domain.

Portugal’s score in the domain of time is 47.5 (the fourth lowest in the EU), with decreased gender inequalities in the distribution of time spent on care activities since 2005. Around 37 % of women and 28 % of men dedicate one hour or more a day to care activities. In couples with children, 87 % of women take care of their family for one hour or more daily, compared to 79 % of men. The gender gap is wider for those aged 25-49 (26 p.p.). Around 78 % of women do cooking and housework every day for at least one hour, compared to only 19 % of men, which is among the widest gender gaps in the EU.

Fewer women (10 %) than men (20 %) participate in sporting, cultural or leisure activities outside the home. Similar proportions of women (7 %) and men (5 %) are involved in voluntary or charitable activities.

Description

Portugal’s score in the domain of power is 46.7 with a significant 24.5 point increase since 2005 (+ 12.8 points since 2015). The domain’s score is progressing at nearly twice the pace of the EU’s score (+ 13.0 points). There are significant improvements in the sub-domains of political and economic decision-making, while progress has stalled in the sub-domain of social power.

Portugal introduced a legislative candidate quota of 33 % in 2006, and the share of women in parliament has increased (from 20 % in the beginning of 2005 to 36 % in 2015). The share of women ministers increased from 14 % to 35 % between 2005 and 2018). The share of women members of parliament also rose from 24 % to 36 % in the same period. Women make up 24 % of members of regional assemblies.

In the sub-domain of economic power, improvements were made. On the board of the central bank, the share of women rose from 0 % to 33 % between 2005 and 2018). Portugal also introduced a legislative quota requiring 33 % of women on the boards of companies in 2017. The share of women more than tripled (from 6 % in 2005 to 19 % in 2018) on the boards of the largest publicly listed companies. Women comprise 36 % of board members of research-funding organisations and 33 % of publicly owned broadcasting organisations.

Description

Portugal’s score in the domain of health is 84.5, with no significant change since 2005 (+ 0.9 points since 2015). In the health domain, Portugal ranks 20th in the EU. Gender equality in health status has slightly improved, while progress has stalled in access to health services. There is no new data for health behaviour.

Self-perceptions of good health increased for women (from 41 % to 44 %) and men (from 51 % to 54 %), in the period 2005 and 2017. Portugal has the third lowest level of health satisfaction in the EU. Health satisfaction increases with a person’s level of education and decreases in proportion to their age. The gender gaps are much wider (to the detriment of women) among those with a low level of education (14 p.p.), lone parents (17 p.p.) and single people (22 p.p.). Life expectancy increased for both women and men between 2005 and 2016. Women on average live six years longer than men (84 years compared to 78 years).

Adequate access to medical care has slightly increased in Portugal. Around 4 % of women and 3 % of men report unmet needs for medical examinations (compared to 7 % and 4 % in 2005). Unmet needs have slightly grown for dental examinations, with 15 % of women and 14 % of men reporting unmet dental needs (compared to 12 % and 11 % in 2005).

Description

Why is there no score for the violence domain?

There is no new data to update the score for violence, which is why no figure is given. Eurostat is currently coordinating an EU-wide survey on gender-based violence, with results expected in 2023. EIGE will launch a second round of administrative data collection on intimate partner violence, rape and femicide in 2022. Both data sources will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024.

Unlike the other domains of the Index, the domain of violence does not measure differences between women’s and men’s situations; rather, it examines women’s experiences of violence (prevalence, severity and disclosure). The overall objective is not to reduce the gaps in violence between women and men, but to eradicate violence completely.

Data gaps mask the true scale of violence

The EU needs comprehensive, up-to-date and comparable data to develop effective policies that combat violence against women.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, women in violent relationships were stuck at home and exposed to their abuser for long periods of time, putting them at greater risk of domestic violence. Even without a pandemic, women face the greatest danger from people they know.

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on violence against women and domestic violence. Portugal signed the Istanbul Convention in May 2011 and ratified it in February 2013. The treaty entered into force in August 2014.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to Portugal in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on mobility and increased isolation exposed women to a higher risk of violence committed by an intimate partner. While the full extent of violence during the pandemic is difficult to assess, media and women’s organisations have reported a sharp increase in the demand for services for women victims of violence. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated pre-existing gaps in the prevention of violence against women and the provision of adequately funded victim support services.

Eurostat is currently coordinating a survey on gender-based violence in the EU but not all Member States are taking part. EIGE, together with the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), will collect data for the remaining countries to have an EU-wide comparable data on violence against women. Data collection will be completed in 2023, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024.

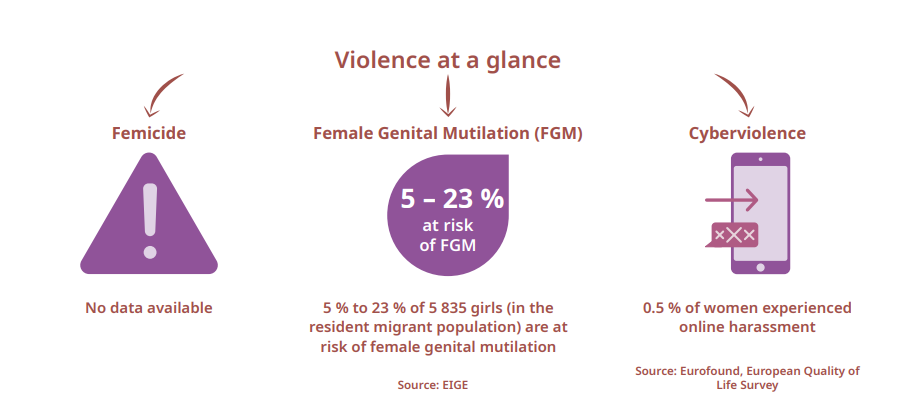

Violence at a glance

-

Femicide

In 2018, over 600 women were murdered by an intimate partner, a family member or a relative in 14 EU Member States, according to official reports. Portugal does not provide comparable data on intentional homicide. - Physical and/or sexual violence

68 % of women who experienced physical and/or sexual violence, experienced it in their own home.

3 % of lesbian women and 3 % of bisexual women were physically or sexually attacked in the past five years for being LGBTI.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey and LGBTI Survey II, 2019 - Harassment

25 % of women experienced harassment in the past five years, and 14 % in the past 12 months.

9 % of women with disabilities experienced harassment in the past five years, and 3 % in the past 12 months .

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey, 2019 - Cyberviolence

5 % of women were subjected to cyber harassment in the past five years, and 1 % in the past 12 months.

Among women aged 16-29, 16 % experienced cyber harassment in the past five years, and 7 % in the past 12 months.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey, 2019 - Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

Between 5 % and 8 % of the 5 835 girls in the resident migrant population were at risk of female genital mutilation in 2011.

Source: EIGE, 2018

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Portugal signed the Istanbul Convention in May 2011 and ratified it in February 2013. The treaty entered into force in August 2014.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to Portugal in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

Femicide

In 2020, 788 women were murdered by an intimate partner, a family member or a relative in 17 EU Member States, according to official reports. Portugal does not provide comparable data on intentional homicide.

Source: Eurostat, 2020

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. Portugal signed the Istanbul Convention in May 2011 and ratified it in February 2013. The treaty entered into force in August 2014.

EIGE/FRA survey

The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) will carry out a survey on violence against women (VAW II) in eight EU Member States (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), which will complement the Eurostat-led data collection on gender-based violence and other forms of interpersonal violence (EU-GBV) in the remaining countries. The use of a unified methodology will ensure the availability of comparable data across all EU Member States. Data collection will be completed in 2023, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024 and its thematic focus on violence against women.

Description

Falta de dados para avaliar a violência contra as mulheres

Não é atribuída pontuação a Portugal no domínio da violência, devido à falta de dados comparáveis a nível da UE.

Durante a pandemia de COVID-19, as restrições à mobilidade e o aumento do isolamento expuseram as mulheres a um maior risco de violência cometida por um parceiro íntimo. Embora a dimensão total da violência durante a pandemia seja difícil de avaliar, os meios de comunicação social e as organizações de mulheres relataram um aumento acentuado da procura de serviços de apoio a mulheres vítimas de violência. Ao mesmo tempo, a pandemia de COVID-19 expôs e agravou as lacunas pré-existentes na prevenção da violência contra as mulheres e na prestação de serviços de apoio às vítimas com financiamento adequado.

O Eurostat está a coordenar um inquérito sobre a violência baseada no género na UE, mas nem todos os Estados-Membros participam. O EIGE, juntamente com a Agência dos Direitos Fundamentais da UE (FRA), irá recolher dados para que os restantes países disponham de dados comparáveis a nível da UE sobre a violência contra as mulheres. A recolha de dados estará concluída em 2023 e os resultados serão utilizados para atualizar o domínio da violência no Índice de Igualdade de Género de 2024.

Um breve olhar sobre a violência

-

Femicídio

Em 2018, mais de 600 mulheres foram assassinadas por um parceiro íntimo, um membro da família imediata ou outro familiar em 14 Estados-Membros da UE, de acordo com relatórios oficiais. Portugal não fornece dados comparáveis sobre o homicídio intencional. - Violência física e/ou sexual

68 % das mulheres que sofreram violência física e/ou sexual vivenciaram-na na sua própria casa.

3 % das lésbicas e 3 % das mulheres bissexuais foram física ou sexualmente atacadas nos últimos cinco anos por serem LGBTI.

Fonte: inquérito da FRA sobre os direitos fundamentais e inquérito às pessoas LGBTI II, 2019 - Assédio

25 % das mulheres foram vítimas de assédio nos últimos cinco anos e 14 % nos últimos 12 meses.

9 % das mulheres com deficiência foram vítimas de assédio nos últimos cinco anos e 3 % nos últimos 12 meses .

Fonte: inquérito da FRA sobre os direitos fundamentais, 2019 - Ciberviolência

5 % das mulheres foram vítimas de ciberassédio nos últimos cinco anos e 1 % nos últimos 12 meses.

Entre as mulheres com idades compreendidas entre os 16 e os 29 anos, 16 % foram vítimas de ciberassédio nos últimos cinco anos e 7 % nos últimos 12 meses.

Fonte: inquérito da FRA sobre os direitos fundamentais, 2019 - Mutilação genital feminina (MGF)

5 % a 8 % das 5835 raparigas da população migrante residente estiveram expostas ao risco de mutilação genital feminina em 2011.

Fonte: EIGE, 2018

A Convenção de Istambul: ponto da situação

A Convenção de Istambul é o tratado internacional de direitos humanos mais abrangente no que diz respeito à prevenção e ao combate à violência contra mulheres e à violência doméstica. Portugal assinou a Convenção de Istambul em maio de 2011 e ratificou-a em fevereiro de 2013. O tratado entrou em vigor em agosto de 2014.

Description

Falta de dados para avaliar a violência contra as mulheres

Não é atribuída pontuação a Portugal no domínio da violência, devido à falta de dados comparáveis a nível da UE.

Femicídio

Em 2020, 788 mulheres foram assassinadas por um parceiro íntimo, um membro da família imediata ou outro familiar em 17 Estados-Membros da UE, de acordo com relatórios oficiais. Portugal não fornece dados comparáveis sobre o homicídio intencional.

Fonte: Eurostat, 2020.

A Convenção de Istambul: ponto da situação

A Convenção de Istambul é o tratado internacional de direitos humanos mais abrangente no que diz respeito à prevenção e ao combate à violência contra mulheres e à violência doméstica. Portugal assinou a Convenção de Istambul em maio de 2011 e ratificou-a em fevereiro de 2013. O tratado entrou em vigor em agosto de 2014.

Inquérito EIGE/FRA

A Agência dos Direitos Fundamentais da União Europeia (FRA) e o Instituto Europeu para a Igualdade de Género (EIGE) realizarão um inquérito sobre a violência contra as mulheres (VAW II) em oito Estados-Membros da União Europeia (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), que complementará a recolha de dados liderada pelo Eurostat sobre violência baseada no género e outras formas de violência interpessoal (EU-GBV) nos restantes países. A utilização de uma metodologia unificada garantirá a disponibilidade de dados comparáveis em todos os Estados-Membros da UE. A recolha de dados estará concluída em 2023 e os resultados serão utilizados para atualizar o domínio da violência no Índice de Igualdade de Género de 2024 e a sua ênfase temática na violência contra as mulheres.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to Portugal in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

Femicide

In 2021, 720 women were murdered by an intimate partner, family member or relative in 17 EU Member States, according to official reports. Portugal does not provide comparable data on intentional homicide.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

Violence at a glance

-

Intimate partner violence

No data is available. Data on intimate partner violence will be updated in 2024 using Eurostat data, complemented by the survey on violence against women carried out by FRA and EIGE.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

-

Sexual harassment at work

No data is available. Data on sexual harassment at work will be updated in 2024 using Eurostat data, complemented by the survey on violence against women carried out by FRA and EIGE.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. Portugal signed the Istanbul Convention in May 2011, and ratified it in February 2013. The treaty entered into force in Portugal in August 2014.

The European Council approved the EU’s accession to the Istanbul Convention on 1 June 2023.

EIGE/FRA survey on violence against women

The Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) will carry out a survey on violence against women (VAW II) in eight EU Member States (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), which will complement the Eurostat-led data collection on gender-based violence and other forms of interpersonal violence (EU-GBV) in the remaining countries. The use of a unified methodology will ensure the availability of comparable data across all EU Member States. Data collection will be completed this year, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024, with its thematic focus on violence against women.

Description

Falta de dados para avaliar a violência contra as mulheres

Não é atribuída pontuação a Portugal no domínio da violência, devido à falta de dados comparáveis a nível da UE.

Femicídio

Em 2021, 720 mulheres foram assassinadas por um parceiro íntimo, um membro da família imediata ou outro familiar em 17 Estados-Membros da UE, de acordo com relatórios oficiais. Portugal não fornece dados comparáveis sobre o homicídio intencional.

Fonte: Eurostat, 2021

Um breve olhar sobre a violência

-

Violência entre parceiros íntimos

Não existem dados disponíveis. Os dados sobre a violência nas relações íntimas serão atualizados em 2024 utilizando dados do Eurostat, complementados pelo inquérito sobre a violência contra as mulheres realizado pela FRA e pelo EIGE.

Fonte: Eurostat, 2021

-

Assédio sexual no trabalho

Não existem dados disponíveis. Os dados sobre o assédio sexual no trabalho serão atualizados em 2024 utilizando dados do Eurostat, complementados pelo inquérito sobre a violência contra as mulheres realizado pela FRA e pelo EIGE.

Fonte: Eurostat, 2021

A Convenção de Istambul: ponto da situação

A Convenção de Istambul é o tratado internacional de direitos humanos mais abrangente no que diz respeito à prevenção e ao combate à violência contra mulheres e à violência doméstica. Portugal assinou a Convenção de Istambul em maio de 2011 e ratificou-a em fevereiro de 2013. O tratado entrou em vigor em Portugal em agosto de 2014.

O Conselho Europeu aprovou a adesão da UE à Convenção de Istambul em 1 de junho de 2023.

Inquérito do EIGE/FRA sobre a violência contra as mulheres

A Agência dos Direitos Fundamentais da União Europeia (FRA) e o Instituto Europeu para a Igualdade de Género (EIGE) realizarão um inquérito sobre a violência contra as mulheres (VAW II) em oito Estados-Membros da União Europeia (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), que complementará a recolha de dados liderada pelo Eurostat sobre violência baseada no género e outras formas de violência interpessoal (EU-GBV) nos restantes países. A utilização de uma metodologia unificada garantirá a disponibilidade de dados comparáveis em todos os Estados-Membros da UE. A recolha de dados estará concluída este ano e os resultados serão utilizados para atualizar o domínio da violência no Índice de Igualdade de Género de 2024 e a sua ênfase temática na violência contra as mulheres.

Thematic focus information

Description

In 2016, 23 % of women and 32 % of men aged 20-49 (potential parents) were ineligible for parental leave in Portugal. Unemployment or inactivity was the main reason for ineligibility for 84 % of women and 52 % of men. The remaining 16 % of women and 48 % of men were ineligible for parental leave due to inadequate length of employment.

Same-sex parents are ineligible for parental leave in Portugal. Among the employed population, 5 % of women and 19 % of men were ineligible for parental leave.

Description

Most informal carers of older persons and/or persons with disabilities in Portugal are women (60 %.) The shares of women and men involved in informal care of older persons and/or people with disabilities several days a week or every day are 8 % and 6 %. The proportion of women involved in informal care is 7 p.p. lower than the EU average, while the involvement of men is 4 p.p. lower. Overall, 10 % of women and 12 % of men aged 50-64 take care of older persons and/or persons with disabilities, in comparison to 7 % of women and 4 % of men in the 20-49 age group. Around 27 % of women carers of older persons and/or persons with disabilities are employed, compared to 55 % of men combining care with professional responsibilities.

There are also fewer women than men informal carers working in the EU. But the gender gap is wider in Portugal than in the EU (28 p.p. compared to 14 p.p. for the EU). In the 50-64 age group, 34 % of women informal carers work, compared to 60 % of men. Women and men in Portugal have the highest unmet needs for professional home care across the EU (86 %).

Description

In Portugal, 59 % of all informal carers of children are women. Overall, 58 % of women are involved in caring for or educating their children or grandchildren at least several times a week, compared to 55 % of men. Compared to the EU average (56 % of women and 50 % of men), slightly more women and men are involved in caring for or educating their children or grandchildren in Portugal. The gender gaps are wider among women and men who are not working (40 % and 28 %) and between women and men working in the private sector (82 % and 72 %).

Portugal reached both Barcelona targets to have at least 33 % of children below the age of three and 90 % of children between the age of three and school age in childcare. Overall, 48 % of children below the age of three are under some form of formal care arrangements, and 46 % of children this age are in formal childcare for at least 30 hours a week. Formal childcare is provided for 93 % of children from the age of three to the minimum compulsory school age (87 % are in formal childcare for at least 30 hours a week). Around 13 % of women and men in Portugal report unmet needs for formal childcare services. Lone mothers are more likely to report higher unmet needs for formal childcare services in Portugal (19 %), compared to couples with children (11 %).

Description

In Portugal, men and women spend an equal amount of time commuting to and from work (around 25 minutes per day). Couples with and without children spend similar time commuting, with women travelling longer than men in both types of couples. Single people spend similar time commuting as people in couples do, with single men travelling around 31 minutes per day compared to 24 minutes per day for single women. Women spend slightly less time commuting than men if they work part-time. Women working part-time travel 17 minutes from home to work and back, and men commute 18 minutes, while both women and men working full-time commute around 26 minutes.

Generally, men are more likely to travel directly to and from work, whereas women make more multi-purpose trips, to fit in other activities such as school drop-offs or grocery shopping.

Description

More women (71 %) than men (60 %) are unable to change their working time arrangements. Access to flexible working arrangements is lower in Portugal than in the EU, where 57 % of women and 54 % of men have no possibility to change their working time arrangements. The private sector provides more flexibility over working time to both women and men than the public sector. Around 66 % of women and 57 % of men private sector employees have no control over their working time arrangements, compared to 88 % of women and 93 % of men public sector employees.

Even though there are more women than men working part-time in Portugal, fewer women (24 %) than men (43 %) part-time workers transitioned to full-time work in 2017. The gender gap is wider than in the EU, where 14 % of women and 28 % of men moved from part-time to full-time work.

Description

Portugal has close to the EU average participation rate in lifelong learning (10 %), with no gender gap. Women (aged 25-64) are more likely to participate in education and training than men regardless of their employment status, except for economically inactive men, who are more likely to participate in lifelong learning than economically inactive women. Conflicts with work schedules are a greater barrier to participation in lifelong learning for men (55 %) than for women (53 %). Family responsibilities are reported as a barrier to engagement in education and training for 41 % of women compared to 22 % of men.

Work schedules are more of an obstacle for participation in lifelong learning in Portugal than in the EU overall, while family responsibilities are reported as an obstacle at around the EU average. In the EU, 38 % of women and 43 % of men report their work schedule as an obstacle, and 40 % of women and 24 % of men report that family responsibilities hinder participation in lifelong learning.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2020 focuses on digitalisation and the future of work. The thematic focus looks at three areas:

- use and development of digital skills and technologies

- digital transformation of the world of work

- broader consequences of digitalisation for human rights, violence against women and caring activities

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2021 focuses on gender inequalities in health. The thematic focus analyses the following aspects of health in the EU:

- health status and mental health

- heath behaviour

- access to health services

- sexual and reproductive health

- the COVID-19 pandemic.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2022 focuses on socio-economic consequences resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The thematic focus analyses the following aspects:

- Childcare

- Long-term care

- Housework

- Flexible working arrangement

The data was gathered using a survey that was carried out in all EU Member States between June and July 2021. Both the survey design and data collection timeframe ensured a comprehensive coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact. The survey was conducted using an international web panel with a quota sampling method based on a stratification approach[1]. It targeted the general population, aged between 20 and 64 years. Representative quotas were designed based on 2020 Eurostat population statistics. Post-stratification weighting was carried out to adjust for differences between the sample and population distribution in key variables and to ensure the sample accurately reflected the socio-demographic structure of the target population.

[1] The data was collected via a web survey using the international panel platform CINT as a main resource. CINT is an international platform that brings together several international panels, reaching more than 100 million registered panellists across more than 150 countries. To fulfil the required sampling in small countries, additional panel providers (IPSOS, TOLUNA, KANTAR) were engaged, which allowed for the same profiling requirements of the respondents and GDPR compliance.

Description

O Índice de Igualdade de Género 2021 centra-se nas desigualdades de género na área da saúde. O foco temático analisa seis aspetos da saúde na UE:

- Situação de saúde e saúde mental;

- Comportamento de saúde;

- Acesso aos serviços de saúde;

- Saúde sexual e reprodutiva;

- A pandemia de COVID-19.

Description

O Índice de Igualdade de Género 2022 centra-se nas consequências socioeconómicas resultantes da pandemia de COVID-19. A ênfase temática analisa os seguintes aspetos:

- Acolhimento de crianças

- Cuidados de longa duração

- Trabalho doméstico

- Mudanças no regime de trabalho flexível

Os dados foram recolhidos através de um inquérito realizado em todos os Estados-Membros da UE, entre junho e julho de 2021. Tanto a conceção do inquérito, como o calendário de recolha de dados, asseguraram uma cobertura abrangente do impacto da pandemia de COVID-19. O inquérito foi realizado recorrendo a um painel Web internacional com um método de amostragem por quotas baseado numa abordagem de estratificação[1]. Este visou a população em geral, com idades compreendidas entre os 20 e 64 anos. As quotas representativas foram concebidas com base nas estatísticas de população do Eurostat para 2020. O coeficiente de correção pós-estratificação foi calculado para ajustar as diferenças entre a amostra e a distribuição da população em variáveis-chave e para assegurar que a amostra refletia com exatidão a estrutura sociodemográfica da população-alvo.

[1] Os dados foram recolhidos através de um inquérito lançado na Web que utilizou a plataforma internacional de painéis CINT como recurso principal. A CINT é uma plataforma internacional que reúne vários painéis internacionais, alcançando mais de 100 milhões de membros de painel registados em mais de 150 países. Para cumprir a amostragem exigida em pequenos países, foram contratados fornecedores de painéis adicionais (IPSOS, TOLUNA, KANTAR), o que permitiu os mesmos requisitos de perfilagem dos inquiridos e a conformidade com o RGPD.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2023 focuses on the socially fair transition of the European Green Deal. Its thematic focus analyses the following aspects:

- Public attitudes and behaviours on climate change and mitigation

- Energy

- Transport

- Decision-making

The data was collected through various surveys, such as the EIGE 2022 survey on gender gaps in unpaid care, individual and social activities, as well as other EU-wide surveys.1 The EIGE survey focused on gender differences in unpaid care, including links to transport, the environment and personal consumption and behaviour.

[1] The following sources were used: the EIGE survey on gender gaps in unpaid care, individual and social activities; the European Social Survey; Eurostat-LFS; EU-SILC; education statistics; and the EIGE’s WiDM.

Description

O Índice de Igualdade de Género de 2023 centra-se na transição socialmente justa do Pacto Ecológico Europeu. Esta ênfase temática analisa os seguintes aspetos:

- Atitudes e comportamentos do público em relação às alterações climáticas e à atenuação dos seus efeitos

- Energia

- Transportes

- Processo de decisão

Os dados foram recolhidos através de vários inquéritos, como o inquérito do EIGE de 2022 sobre as disparidades de género na prestação não remunerada de cuidados e em atividades individuais e sociais, bem como outros inquéritos à escala da UE.1 O inquérito do EIGE centrou-se nas diferenças de género na prestação não remunerada de cuidados, incluindo ligações com os transportes, o ambiente e o consumo e comportamento pessoais.

[1] Foram utilizadas as seguintes fontes: o inquérito do EIGE sobre as disparidades de género na prestação não remunerada de cuidados e em atividades individuais e sociais; o Inquérito Social Europeu; o Eurostat-IFT; o EU-SILC; estatísticas sobre a educação; e o relatório WiDM do EIGE.