Gender differences on household chores entrenched from childhood

Housework is the most unequally shared of the three most common forms of unpaid care, the other two being childcare and long-term care for older people and people with disabilities and other chronic conditions[1] .

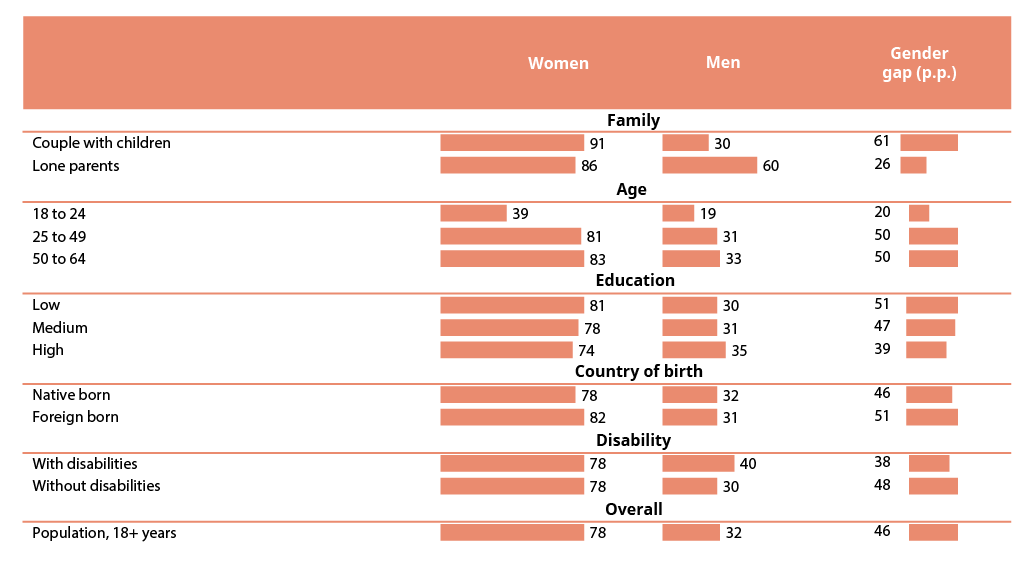

About 91 % of women with children spend at least an hour per day on housework, compared with 30 % of men with children. The latest available data shows that employed women spend about 2.3 hours daily on housework; for employed men, this figure is 1.6 hours. Gender gaps in housework participation are the largest among couples with children, at 62 p.p. (Figure 15), demonstrating an enduring imbalance in unpaid care responsibilities within families[2] .

Research shows that the parental role model is the primary mechanism for entrenching gender roles in terms of housework responsibilities, ensuring they pass from one generation to the next, especially from fathers to sons (Giménez-Nadal et al., 2019). Although the smallest gender gaps in housework participation are among those aged 18–24 years (20 p.p.), only 19 % of young men spend an hour on cooking and housework a day, compared with 39 % of young women (Figure 15). As most young people of this age live with their parents[3] , it is clear that adolescent girls and young women do more unpaid work in the childhood home than their male counterparts – and gender roles, divisions and habits start early.

Figure 15. Women and men cooking and/or doing housework, every day by family composition, age, education level, country of birth and disability (%, 18+ years, EU, 2016)

Source: Authors’ calculation, Eurofound, European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS), 2016.

The burden of unpaid care work is greater for women in non-standard and low-paid jobs. EWCS data shows that women in temporary jobs or without a formal contract spend twice as much time providing unpaid care daily as women employed in permanent jobs (EIGE, 2021d). One reason is the lack of economic resources to rely on external services. Yet women in irregular and temporary jobs are unable to access more stable jobs because of their substantial care responsibilities. In addition, FRA data shows that in most EU countries migrant women are less likely than native women to be in paid work because of care duties (FRA, 2019).

Education levels affect the likelihood of women and men spending an hour a day on housework and cooking – in opposing ways. While the share of women spending this much time on housework decreases with higher educational level (81 % of those with a low level of education, 78 % with a medium level and 74 % with a high level), the opposite is true for men (Figure 15).

This is consistent with EIGE (2021d) findings showing that highly skilled employed women often outsource household chores to cut their time spending this much time on housework so that they can engage more in paid work. Outsourcing cooking, cleaning, ironing, gardening, caring for pets, etc., has grown because there are more women in paid jobs and little headway has been made on men assuming more unpaid care duties at home (Barone and Mocetti, 2011; Forlani et al., 2015; Raz‐Yurovich, 2014; Raz-Yurovich and Marx, 2019).

Housework services are often provided by migrant women or women from a lower socioeconomic background, and the resulting income is frequently undeclared. It is a development that transfers gender inequalities within households into the global care chain (Morel and Carbonnier, 2015).