Digital skills and training

Digital skills have increasingly become a basis for global competitiveness, boosting jobs and growth. Digital societies require digital competencies if they are to ensure full participation of people in social and working life. The internet has been of paramount importance in working towards high-quality education at all levels, while the COVID-19 crisis has shown that most jobs can be done remotely using technology.

The crisis has caused education and training to be moved online or digitalised, placing the digital skills and competence of learners and teachers/trainers front and centre when it comes to engaging in learning at all levels.

Building on the various concepts used to define digital skills (Kaarakainen et al., 2017) and the EU Digital Scoreboard (Digital Economy and Society Index, Women in Digital (WiD)), the following analysis looks at gender differences in information, communication, problem-solving and software skills[1] and in training opportunities to advance those skills.

Advanced digital skills of women and gender equality go hand in hand

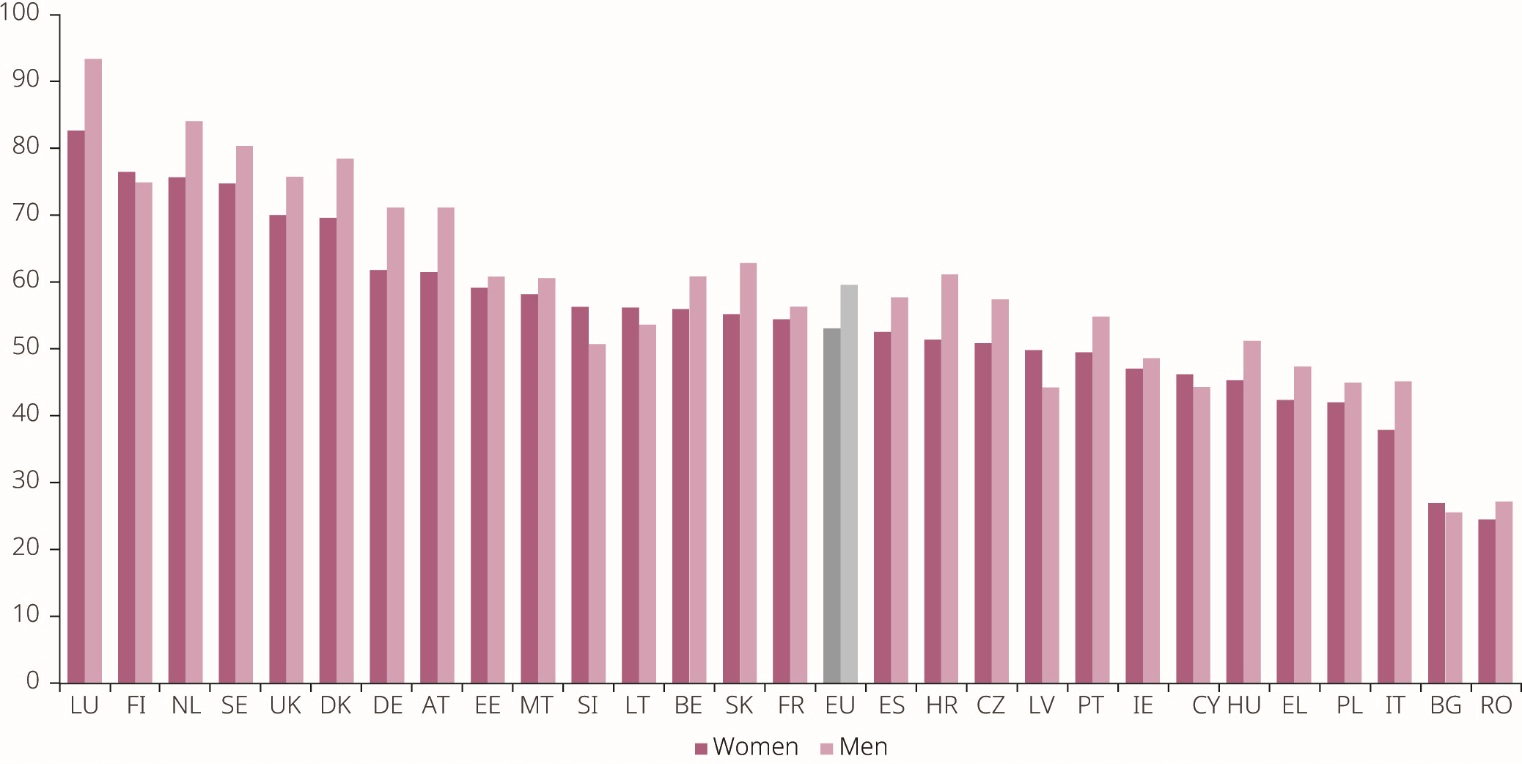

The WiD Scoreboard monitors women’s participation in the digital economy. Its second dimension looks at women’s internet use skills, as measured by three indicators: at least basic digital skills, above basic digital skills and software skills (Figure 31). Luxembourg, Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden have the highest scores in internet user skills, while Romania, Bulgaria, Italy and Poland score lowest.

Only six Member States (Finland, Slovenia, Lithuania, Latvia, Cyprus and Bulgaria) show women scoring higher than men on internet user skills. The biggest gender gaps (to women’s disadvantage) are in Luxembourg, Austria and Croatia.

Figure 31. Internet user skill scores by sex, 2017

The correlation between the Gender Equality Index and internet user skills suggests that these two areas reinforce one another. Women’s internet skills are highest in Luxembourg, which ranks 10th on the Gender Equality Index, while Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Denmark are in the top rankings on both indices.

Gender divide in digital skills widens with age

Given the likely future of jobs, it is important to distinguish between basic and advanced digital skills. While basic digital skills, such as the use of search engines or digital bank services, are necessary, advanced digital skills open opportunities for access to well-paid jobs for which there is significant demand in the European digital economy.

Both types of skills are increasingly essential in the labour market. As noted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, workers who are successful in penetrating competitive labour markets typically have a mix of basic and advanced digital skills (OECD, 2018a).

In the EU, men often have more advantages than women when it comes to the digital skills (information, communication, problem-solving and software skills) necessary to thrive in the digitalised world of work. This is particularly evident among older people (aged 55 or older). Finland, the Netherlands, Denmark, the United Kingdom and Sweden have the highest shares of women with above basic digital skills, while Greece, Poland, Italy, Bulgaria and Romania have the lowest shares.

The correlation between Gender Equality Index scores (domain of work, subdomain of participation, domain of money) and the shares of women with above basic skills confirms that countries with high shares of digitally skilled women also have higher gender equality in the labour market.

Young women and men are the most digitally skilled generation and benefit equally from basic and above basic digital skills – 59 % of women and 60 % of men aged 16–24 have above basic digital skills (Figure 32). Finland, Malta and Croatia have the highest shares of young women with above basic digital skills, while Italy, Bulgaria and Romania have the lowest shares.

However, at a later age, the gender divide widens, with most older people having low to basic digital skills. Finland, Denmark and Sweden have the highest shares of digitally skilled women aged 55–74, while Greece, Bulgaria and Romania have the lowest shares. Aside from generational and country differences, women generally experience bigger obstacles in trying to improve their digital skills, owing to factors such as gender stereotypes, family status, and the broader societal, economic and technological environment (OECD, 2018a).

The digital skills of young people are improving quickly, with a somewhat faster pace observed for men than for women. Between 2015 and 2019, the share of women aged 16–24 with above basic digital skills increased by 7 p.p., compared with 9 p.p. for men, with no substantial gender gap observed during this period. Greece, Cyprus and Ireland made the greatest progress in 4 years, while the shares of young women with above basic digital skills declined in Luxembourg, Denmark and Bulgaria.

Across the EU, the gender gap decreased among those aged 25–54 (– 4 p.p. in 2015, – 3 p.p. in 2019). Cyprus, Austria and Ireland progressed most, while Luxembourg, Latvia and Denmark showed least progress during this period. Among older people (aged 55 or older), progress was slower, and older people still remain the least digitally skilled age group, with a gender gap of around – 7 p.p. in 2019 (compared with – 6 p.p. in 2015)[2].

Figure 32. Levels of digital skills of individuals in the EU, by sex and age group (%), 2019

In addition to gender differences in levels of digital skill in some age groups, women and men also acquire different types of digital skills (see subsection 9.1.1.). The gender gap in overall digital skills is primarily associated with problem-solving digital skills[3], to the detriment of women.

More men than women have above basic digital skills in problem-solving and software skills, with a smaller gap evident in information and communications skills. The Council recommendation ‘Upskilling pathways: new opportunities for adults’ seeks to improve low-qualified adults’ access to basic skills, including basic digital skills (European Commission, 2016c).

Differences are also found across age groups (Figure 33). Women aged 25–54 have higher information and communication skills than men, while the opposite is true for problem-solving and software skills. Older men outperform older women (aged 55 or older) on all dimensions except communications skills. There are almost no gender gaps among the younger generation, suggesting the importance of levelling digital problem-solving and software skills among women and men in older age groups in order to close the gender gap in overall digital skills (EIGE, 2019a).

The digital skills of both women and men increase with level of education. Gender differences in all types of digital skills are largest among those with low education, particularly women. Across all levels of education, women have fallen behind in problem-solving and software skills.

Figure 33. Percentages of people (aged 16–74) with above basic digital skills in the EU, by type of skill, gender and age group, 2019

Broader gender inequalities limit women’s training opportunities

Given the extent to which digital innovations are progressing, workers must adapt by undertaking ongoing training to improve their digital skills, depending on their sector and specific tasks. It is also important to ensure that people entering the labour market have the necessary skills, meaning that education systems play a crucial role. While age influences participation in both basic and advanced skill enhancement activities, gender inequality tends to have a negative impact, especially in relation to lifelong learning and re-skilling or upskilling.

Negative gender stereotyping often deters women from selecting ICT-related training. Even where women have access to advanced training opportunities through their existing professional networks, the burden of unpaid care or domestic responsibilities may prevent them from availing themselves of these opportunities (EIGE, 2018b, 2018d).

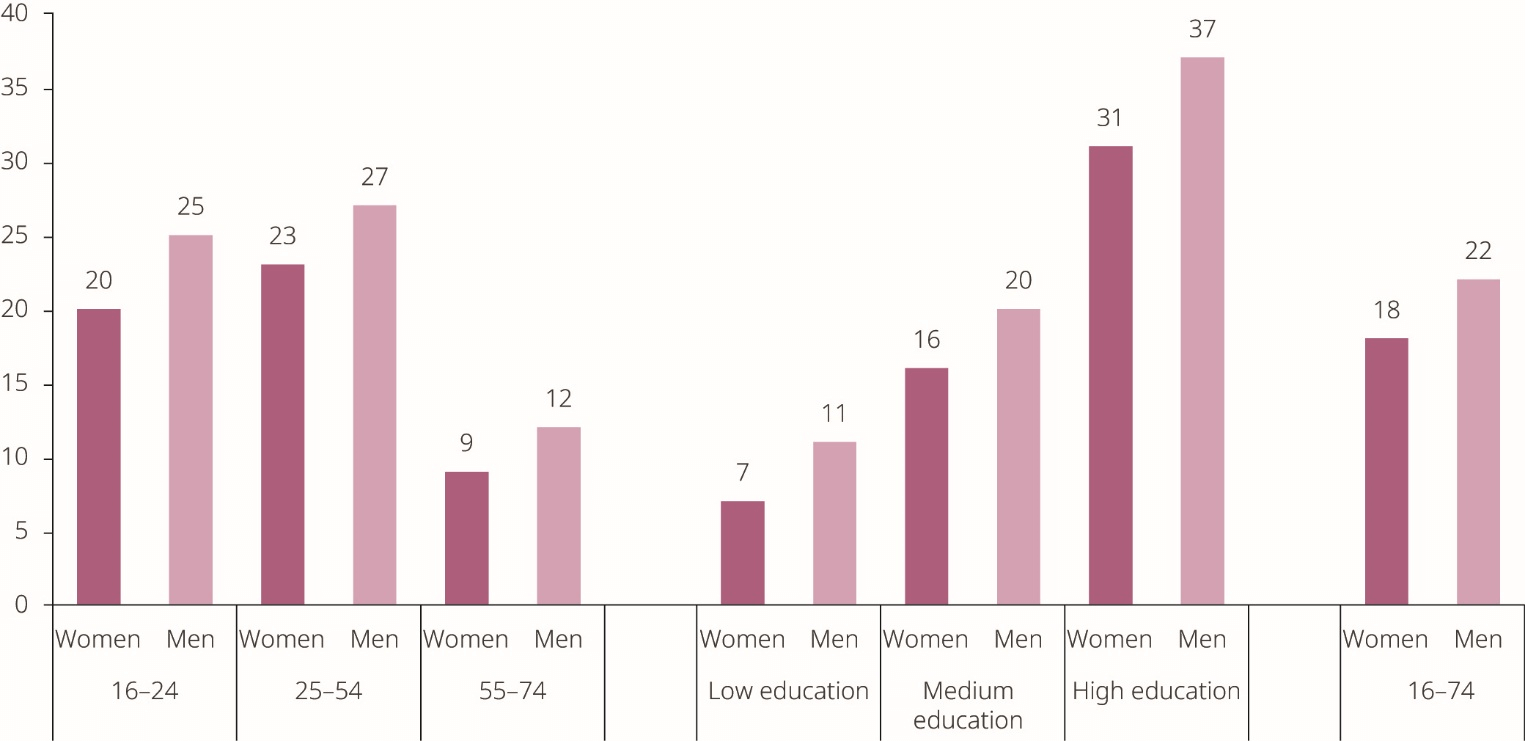

In 2018, around one in five people (18 % of women compared with 22 % men) had carried out at least one training activity in the previous 12 months to improve skills relating to the use of computers, software or applications (Figure 34). Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands had the highest shares of women who had carried out at least one such training activity, while Greece, Italy, Hungary, Croatia and Cyprus had the lowest shares.

Men were more likely to have participated in training than women, in all age groups and across different levels of education. Women with higher education aged 25–54 were more likely to have been involved in training to increase their digital skills than other women.

Figure 34. Percentages of people (aged 16–74) in the EU who carried out at least one training activity to improve computer, software or application skills, by sex, age, and education level, 2018

Although most women and men (62 % and 67 %, respectively) consider themselves sufficiently skilled with digital technologies to benefit from digital and online learning opportunities (European Commission, 2017), a range of barriers can put participation in training out of reach. For both women and men, lack of time is the most relevant barrier, usually due to work schedules, caring responsibilities and household duties.

Although women aged 25–64 are more likely to participate in lifelong learning than men (12 % and 10 %, respectively), on average 40 % of women – compared with 24 % of men in the same age group – report that they cannot participate in in lifelong learning because of family responsibilities (in Cyprus, Malta, Greece, Austria and Spain, more than 50 % of women identified this reason)[4]. Work schedule conflicts are bigger barriers for men in most EU countries (EIGE, 2019b).

Finally, around one in four Europeans perceive a lack of training opportunities as an obstacle to increasing their digital skills, highlighting their awareness of the importance of digital skills training. A similar proportion do not know what specific skills to improve (European Commission, 2020b).