What does gender budgeting have to do with women’s and men’s lived realities?

Take a look at this recent picture of the European Council’s members. How many women and how many men can you see?

Photo accessed from: https://newsroom.consilium.europa.eu/events/20190322-european-council-march-2019-day-2

Consider "women’s and men’s lived realities" by looking at the composition of the European Council, and ask yourself: Why do you think there are more men than women?

In EU Member States, both paid work and unpaid care work exists. These different kinds of work are performed by both women and men. Consider:

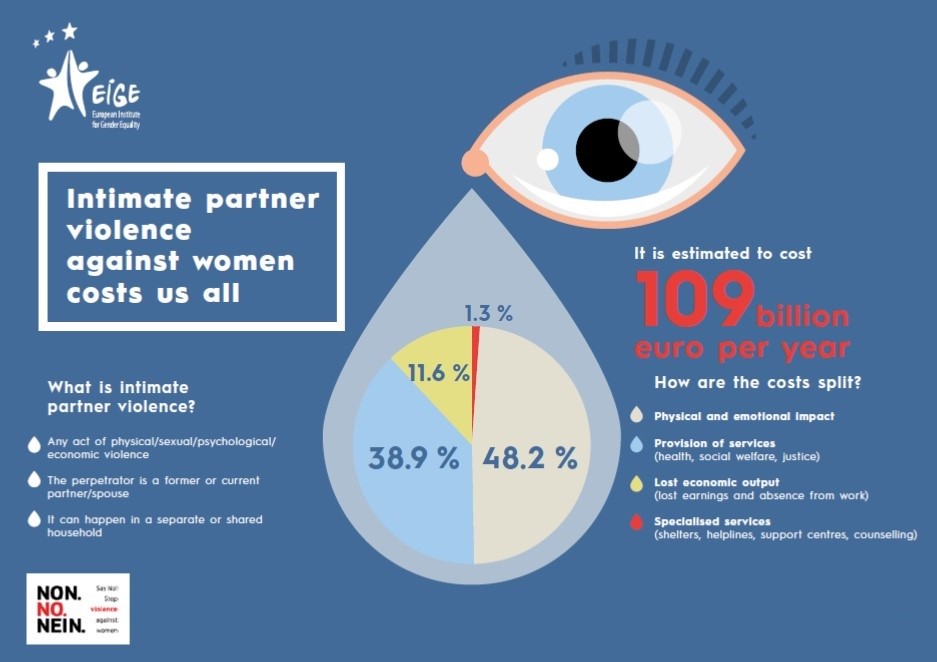

Inequalities between women and men are found not only in the paid and unpaid spheres. They cut across other dimensions as well, such as health, power, education, and time use in general. One of the most brutal manifestations of inequalities between women and men is violence against women, which affects all sectors and spheres of life. Eradicating violence against women is a priority of the EU and its Member States. This commitment is affirmed in the EU’s principal gender equality policy[1] documents. Most recently, the EU reaffirmed its commitment by signing the leading regional legal instrument on gender-based violence, the Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (the Istanbul Convention). Eradicating violence requires adequate budgets, which should be considered within the EU Funds' programming cycle.[2]

Intimate partner violence costs us all.

©EIGE.

To learn more about gender inequalities in your country, consult EIGE’s Gender Equality Index. There, you can access statistics on a range of spheres, including work, money, knowledge, time, power, health, violence against women and intersecting inequalities, i.e. when gender inequalities interact with other socio-demographic characteristics such as age, nationality, religion, sexual preferences orientation and disabilities.

Here are some examples of gendered patterns of employment, care work and violence in four EU Member States[3]:

| Czechia | |

|---|---|

| Employment rates |

- The full-time equivalent employment rate is 46 % for women and 65 % for men.

- 10 % of women work part-time, compared with 3 % of men. |

| Care-related time use |

- 33 % of women care for family members for at least 1 hour per day, compared with 20 % of men.

- 86% of women and 12% of men cook and do housework every day. |

| Violence against women |

- 32 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15.

- Violence against women costs Czechia an estimated EUR 4.7 billion per year through lost economic output, service utilisation and personal costs. |

| Estonia | |

|---|---|

| Employment rates |

- The full-time equivalent employment rate is 50% for women and 64% for men.

- 15 % of women work part-time, compared with 7 % of men. |

| Care-related time use |

- 35 % of women care for family members for at least 1 hour per day, compared with 31 % of men.

- 76% of women and 45% of men cook and do housework every day. |

| Violence against women |

- 34 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15.

- Violence against women costs Estonia an estimated EUR 590 million per year through lost economic output, service utilisation and personal costs. |

| Germany | |

|---|---|

| Employment rates |

- The full-time equivalent employment rate is 40 % for women and 59 % for men.

- 47 % of women work part-time, compared with 11 % of men. |

| Care-related time use |

- 50% of women care for family members for at least 1 hour per day, compared with 30 % of men.

- 72% of women and 29% of men cook and do housework every day. |

| Violence against women |

- 35 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15.

- Violence against women costs Germany an estimated EUR 36 billion per year through lost economic output, service utilisation and personal costs. |

| Spain | |

|---|---|

| Employment rates |

- The full-time equivalent employment rate is 36 % for women and 50 % for men.

- 25% of women work part-time, compared with 8% of men |

| Care-related time use |

- 56 % of women care for family members for at least 1 hour per day, compared with 36% of men.

- 85% of women and 42% of men cook and do housework every day. |

| Violence against women |

- 22 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15.

- Violence against women costs Spain an estimated EUR 21 billion per year through lost economic output, service utilisation and personal costs. |