Gender pay gap in ICT and platform work

Despite recent policy actions at EU and Member State levels, the gender pay gap persists. In 2018, on average, women’s gross hourly pay was 14.8 % lower than men’s (Eurostat, 2020). The pay gap stems from a combination of factors, including occupational and sectoral segregation, part-time or temporary work, gender stereotypes and norms, difficulties in reconciling work and private life, discrimination, opaque wage structures, and undervaluing of women’s work and skills (European Commission, 2009, 2018a, 2018g).

Major biases, such as horizontal and vertical segregation in education and the labour market, are crucial factors underpinning the pay gap (EIGE, 2019c; Eurostat, 2018). A large share of the pay differences (around one third) results from the fact that women and men work in different economic activities and occupations (Eurostat, 2018), with those that are female dominated often being underpaid and undervalued.

Both women and men are well paid in ICT but the gender pay gap persists

Attracting women to well-paid ICT and STEM jobs is seen as an important policy tool to reduce the gender pay gap (EIGE, 2019c). In these generally male-dominated jobs, the pay tends to be higher than in much of the EU labour market, including the jobs requiring equally high qualifications in which women tend to work, such as in the health sector (EIGE, 2018d).

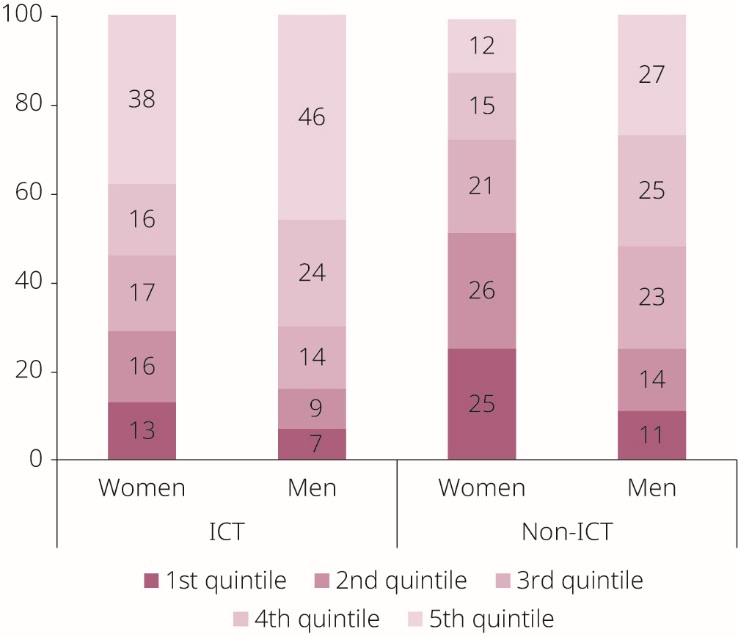

In 2015, the average monthly income of both women and men working in ICT was higher than the average income of women and men working elsewhere (Figure 50). Of men working in ICT, 70 % had a monthly income falling into the top two income quintiles (52 % of men working elsewhere), compared with 54 % of women working in ICT (28 % of women working elsewhere)[1].

Figure 50. Income distribution of women and men (aged 20–64) working in ICT and non-ICT sectors (%), EU, 2015

Despite earning more than other female workers, women in ICT have lower monthly earnings than men. This reflects gender differences in the average working hours of women and men, their different positions within the ICT sector and differences in their hourly pay.

In 2014 in the EU, the gender pay gap among ICT professionals and technicians was 11 %. This is among the lowest occupational gender pay gaps across all sectors in the EU (EIGE, 2019c). In all Member States, the gender pay gap in the STEM sector is lower than the general pay gap, except in Ireland and Czechia (EIGE, 2019c).

Overall, smaller gender pay gaps in occupations with very few women employees may not necessarily point to gender-equal opportunities but, rather, to large differences in educational qualifications (and thus pay) among the average employed women and men.

Gender pay gaps are often reproduced in the context of platform work

The general assumption has been that platform work will help to eliminate the gender pay gap and gender inequalities by improving women’s access to the labour market (Barzilay and Ben-David, 2016). For instance, using gender-blind algorithms has the potential to promote equal access to jobs and more flexible work schemes that would allow women to assume dual roles as employees and caregivers (Barzilay and Ben-David, 2016; Liang et al., 2018).

Of female platform workers in the United States, 86 % believe that gig work offers the opportunity to earn equal pay to their male counterparts (41 % of female gig workers believe that traditional work offers this opportunity) (Hyperwallet, 2017).

Recent studies suggest that the platform economy is not an easy remedy for the gender pay gap (Silbermann, 2020). Estimates vary, with studies finding pay gaps ranging from 4 % in the EU online labour market (PeoplePerHour) (JRC, 2019b) to 7 % in Uber (Cook et al., 2018) and 20 % in Amazon Mechanical Turk (Adams, 2020).

A mixed picture emerged from an ILO study of five platforms in 2017, with women having a higher hourly pay rate than men on one platform (Microworkers) and an almost equal pay rate on another (Clickworker), while there was a pay gap of between 5 % and 18 % on other platforms (AMT, Crowdflower, Prolific) (ILO, 2018c).

Just as in the traditional economy, a small gender pay gap may hide a number of imbalances, such as lower pay for women despite their higher educational qualifications or skills. There is evidence that the pay gap affects women with young children in particular, especially when their domestic responsibilities affect their ability to plan and complete work online (Adams, 2020).

The ILO (2018c) study accounts for both the paid and unpaid work that underpins platform work: searching for tasks, taking unpaid qualification tests, researching clients to mitigate fraud and writing reviews, as well as unpaid or rejected tasks and tasks ultimately not submitted. In a typical week, both women and men spend about 6 hours doing unpaid tasks, while women (on average) do fewer hours of paid work (around 16 hours) than men (close to 20 hours) (ILO, 2018c).

Gender segregation and other gendered practices are common on platforms

Depending on the platform, pay inequalities can be due to several factors, including biased algorithms and behaviours – on the part of both workers and clients – that reflect broader biases in the traditional labour market.

The segregation of the labour market is reflected in platform work, with the imbalanced division of care between women and men restricting women’s choices more than those of men. Gender segregation within and between platforms (see subsection 9.2.2) persists, as a result of very strong gender stereotyping in platforms, with women more likely to be selected for ‘female-type’ jobs (writing, translation) and less likely to be selected for ‘male-type’ jobs (software development) than equally qualified male candidates (Galperin, 2019).

There are some signs that customer ratings – which often affect pay levels (ILO, 2018c) – can discriminate on racial and gender grounds (Rosenblat et al., 2017), favouring men over women (Kim, 2018). Hannák et al. (2017) report that workers’ race and gender affect the social feedback that they receive, although the impact is different on each platform. A survey carried out in the United States showed that one third of female platform workers adopted a gender-neutral username in order to maintain anonymity (Hyperwallet, 2017).

However, data from an online crowdworking platform in which workers’ gender is not revealed to the employer showed that women earned on average 82 % of men’s earnings (Adams and Berg, 2017). This shows that while direct gender discrimination may have a role in pay inequality, other factors are also at play.

Studies often conclude that women’s behaviour and personal choices in doing platform work are the reason for their unequal pay (Liang et al., 2018). A study on Uber concluded that the pay difference experienced by women and men was explained by the fact that men drove faster, allowing them to complete more rides per hour. Men were also more likely to drive in less safe areas and during times that yielded a higher fee (Cook et al., 2018).

Similar reasons were given to explain older drivers (aged 60 or older) earning almost 10 % less than drivers who are 30 years old (Cook et al., 2018). Where platform workers themselves set the pay, women tend to set their rates at lower levels (Barzilay and Ben-David, 2016; Liang et al., 2018) and, in general, take up lower paid jobs (Foong et al., 2018). While the cause is not entirely clear from the available research, it is a result of women’s lower propensity to negotiate salary, alongside gendered expectations about remuneration (among both workers and employers) (Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2017).

The explanation for lower pay cannot be reduced to individual behaviour. There is a structural bias in the gender division of unpaid work and care responsibilities, restricting women’s choices in the labour market in general, including in relation to platform work. For instance, women appear to be less able to select longer, more complex tasks – some of which require a quiet working environment – because of interruptions from young children or adult family members (Adams and Berg, 2017).

The platform may prefer to allocate work to those with higher ratings, restricting the ability of those with lower ratings to make a decent living (Ropponen et al., 2019). This disadvantages those who are working fewer hours, particularly women with care responsibilities, and those with poor health.

A study of the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform showed that women earned 20 % less per hour on average, with half of the gap explained by the fact that women had more fragmented working patterns, with consequences for their task completion speed (Adams, 2020). Weak collective representation of platform workers (see subsection 9.2.3) prevents efforts at collective salary negotiation, often leaving the responsibility for salary negotiation to workers. This is likely to put women at a disadvantage, as discussed above.