Digitalisation and work–life balance

The use of mobile devices, digitalisation of working processes and online communication allow more flexibility in where and when people work. Flexible working arrangements typically relate to how much, when and where employees can work (Eurofound, 2017b; Laundon and Williams, 2018).

This flexibility in time and place is typically assumed to allow work to fit better around home and family responsibilities (Eurofound, 2020c). There is indeed evidence that the use of ICT (smartphones, tablets, laptops, desktop computers) to work outside the employer’s premises can help to facilitate better work–life balance. Workers report shorter commuting times, greater working time autonomy, more flexibility in working time, better productivity and improved overall work–life balance (Eurofound and ILO, 2017). There is evidence that mothers using flexitime and teleworking are less likely to reduce their working hours after childbirth (Chung and Van der Horst, 2018).

The European Commission’s Work–Life Balance Directive (adopted in 2019) sees flexible working arrangements as one of the key tools to reconcile work and life for parents and carers and to contribute to the achievement of equality between women and men in the labour market. The Gender Equality Index 2019 showed that work–life balance challenges are closely linked to gender inequalities, and that flexible working arrangements can increase gender-equal opportunities (EIGE, 2019b). A strong link was established between the score for the domain of time (which measures gender equality in engagement in care and social activities) and the availability of some flexible working arrangements, such as women’s ability to set their own working hours.

The rest of this section investigates how technology-based flexibility supports or undermines workers’ work–life balance. Again, the focus is on the ICT sector and platform work, where technology plays a particularly important role.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly the resulting quarantine, created a natural experiment, in which the limits of extensive teleworking have been explored. By April 2020, 35 % of men and 39 % of women had begun to work from home as a result of the pandemic, while only 11 % of men and 10 % of women had done so previously. Among younger women (aged 18–34), as many as 50 % started working from home (compared with 37 % of men of that age) (Eurofound, 2020b). The situation has shown the unused potential of technology, as well as the limitations of such arrangements for work–life balance. For instance, taken together with tele-schooling and closure of childcare facilities, home working has intensified work–life conflicts for many families with children (Eurofound, 2020b)(Eurofound, 2020b). Telework is evidently not a sustainable solution to solve childcare shortages and does not remove the need for other work–life balance policies.

High flexibility and autonomy in ICT, but also more work–life spillover effects

The first condition for technology-driven flexibility to support work–life balance is workers’ autonomy and control over their working time and place. The Work–Life Balance Directive envisages giving workers the right ‘to request flexible working arrangements for the purpose of adjusting their working patterns, including, where possible, through the use of remote working arrangements, flexible working schedules, or a reduction in working hours, for the purposes of providing care.’ In other words, the directive calls for flexibility controlled by the employee, rather than the employer.

In the ICT sector, digitalisation provides the greatest opportunities for work that is flexible in both time and location (see subsection 9.2.3). In spite of above average flexibility and control over their working time, women and men in ICT are only slightly more satisfied with the fit between their working hours and other responsibilities than others: 87 % of women and 84 % of men in ICT view their working hours as fitting well or very well with their family or social commitments outside work, which is only somewhat higher than among other employed women and men (84 % and 79 %, respectively)[1].

One reason may be that the use of technology can blur the boundaries between work and private life. In the past, temporal and physical boundaries existed between work and home (McCloskey, 2016), but digital technology has now created both the possibility and the expectation of being constantly online and available. The use of smartphones can create high after-hours availability pressure (Ninaus et al., 2015), give rise to difficulties with psychologically detaching from work during free time (Mellner, 2016), and have a negative impact on work–life balance and stress levels (Harris, 2014). Family members can make personal demands on workers while they are teleworking at home (McCloskey, 2016), which increases the need to multitask and blurs boundaries (Glavin and Schieman, 2012; Schieman and Young, 2010).

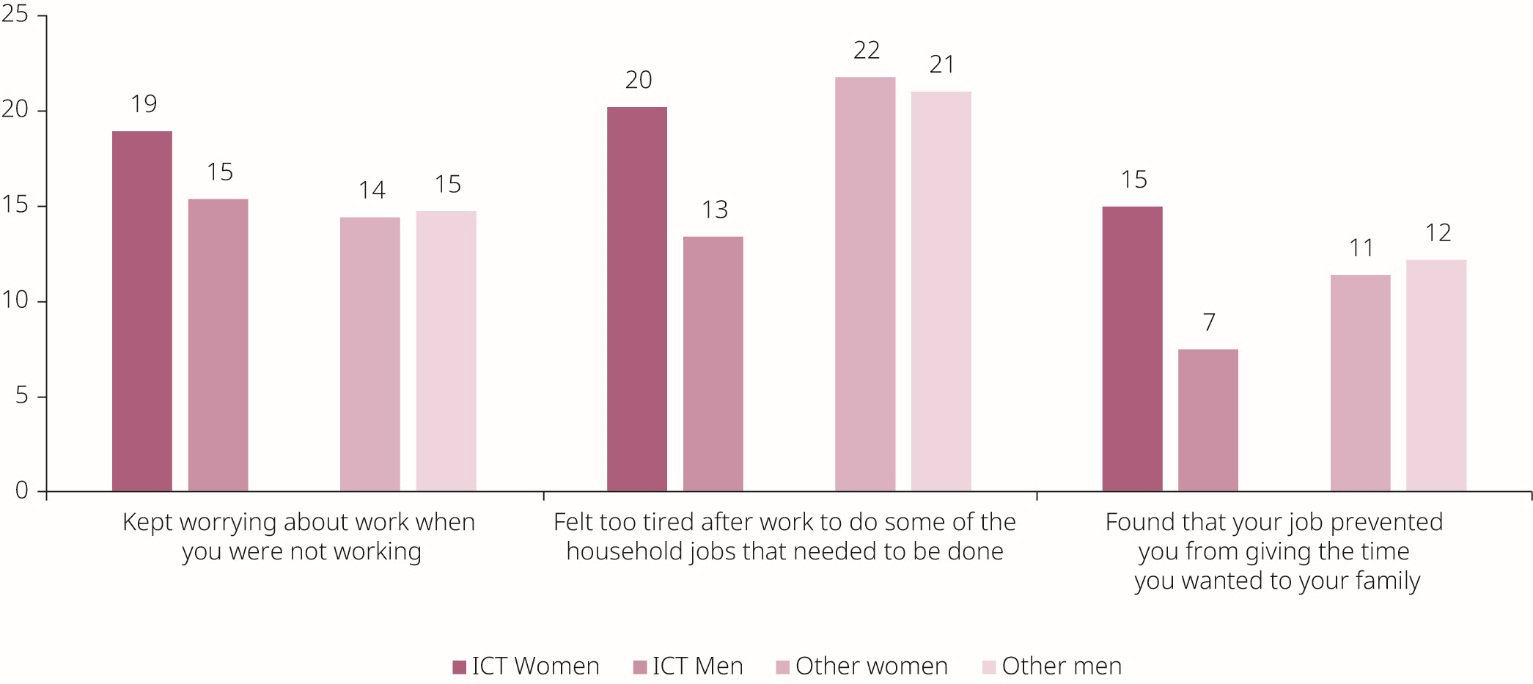

Data suggests that this spillover effect is more often felt by women working in ICT than their male ICT peers or women in other sectors, although the differences are not dramatic (Figure 49). There may be several reasons for such gaps. One may be that women in ICT – as in in the rest of the economy – have primary responsibility for home and family affairs. This double burden may be particularly challenging while teleworking from home or with the requirement to be constantly available for work. For men, however, the spillover effects are smaller when they work in ICT, compared with men in other sectors. Some studies indicate that women’s motivation to work from home (or to take up self-employment) is to obtain a higher degree of flexibility and autonomy that will better accommodate work and family responsibilities, while men report labour market and job-related motivations (Hilbrecht et al., 2017). Women’s time tends to be fragmented and characterised by blurred boundaries between leisure time and unpaid care, with phenomena such as contamination (leisure time spent in the presence of children) and fragmentation (interruption of leisure time to care for children) (European Parliament, 2016).

Figure 49. Percentages of employees (aged 20–64) frequently perceiving spillover from work to home and family in the EU, by occupational group and gender, 2015

The slightly higher spillover felt by women working in the ICT sector is all the more remarkable given that they are on average younger and have fewer daily or weekly childcare responsibilities than women working in other sectors. In 2015, 34 % of women and 28 % of men in the ICT sector cared for children daily, in comparison with 42 % and 25 %, respectively, in other sectors[2]. It has been suggested that younger generations of women working in ICT may delay having children, with the postponement of parenthood generally more common among women who work in higher paid jobs or who have non-standard contracts (EIGE, 2018d).

Several studies have shown that flexible working results in the expansion of the work sphere (Chung and Van der Lippe, 2018). Digitalisation can contribute to overall intensification of work and overworking (Peña-Casas et al., 2018), as can self-managing: workers with apparently high levels of autonomy work beyond their limits, burning out and severely harming their health and personal relationships (Pérez-Zapata et al., 2016). Women are more likely to experience work-related burnout than men, and when they do they feel more emotional exhaustion, while men tend to feel burnout as depersonalisation (distancing themselves psychologically from clients and co-workers) (Purvanova and Muros, 2010). Working in male-dominated jobs may add to the overall stress for women, for reasons such as conflicting gender-role expectations arising from working in a male-dominated occupation while being a woman and a carer. Inconsistency between the requirements of a woman’s work and expectations about her gender role may result in significant role conflict (Purvanova and Muros, 2010).

Certain forms of platform work can support or undermine work–life balance

Although platforms vary significantly in their design and the autonomy they provide to their workers, they are nevertheless often characterised by a higher degree of flexibility and autonomy than ‘regular’ work as an employee. Indeed, flexibility of when and where to work is among the most significant reasons to pick up platform work (JRC, 2018). For example, women are more likely to perform online tasks via platforms because it is difficult for them to work outside the home, while men are more likely to do so to top up income from their other work (Adams and Berg, 2017). Of people working across five English-speaking microtask platforms, 15 % of women and 5 % of men said that they could work only from home because of care responsibilities (ILO, 2018c). One in five women had a child under 5 years old, while 30 % of women and 10 % of men platform workers had been engaged in caring activities prior to taking up platform work. The flexibility of platform work provides opportunities to take up some work and to combine it with childcare and other care responsibilities.

I can only work from home because my husband is away the whole day at work and I have to take care of my children and home. (Respondent on CrowdFlower, Italy)

Source: ILO (2018c)

As discussed in subsection 9.2.3, platforms vary significantly in the autonomy they afford their workers. The degree of control that workers have over their own working time, workplace and working arrangements is the key to their work–life balance. For example, platforms providing certain services (e.g. ride-hailing or clickwork) often adopt practices that limit worker autonomy and flexibility, especially for workers who rely on platform work as their main source of income (Eurofound, 2018b; ILO, 2018a). Employer-oriented flexibility – where either the platform or the client is in charge – creates unpredictable and unreliable schedules, often involving a considerable amount of unpaid time spent searching for work and the need to be available on demand (Eurofound, 2018b; ILO, 2018a). This undermines work–life balance (Ropponen et al., 2019). Women have been shown to suffer particularly from the increased work–life spillover effects created by employer-oriented schedules (Lott, 2018), with negative effects on working time quality and increased stress levels (Eurofound, 2019). Directive (EU) 2019/1152 (European Parliament, 2019a) on transparent and predictable working conditions is a direct follow-up to the proclamation of the European Pillar of Social Rights and states (among other things) that workers with very unpredictable working schedules (e.g. on-demand work) need reasonable notice of when work will take place.

I feel in control of the work but have no control over when work will be available.

Source: ILO (2018c)

Women often take up platform work alongside unpaid care work, and such arrangements may support work–life balance but may also present challenges. While platform work provides opportunities to take up jobs in between care and other responsibilities, highly flexible schedules may require complex logistics that involve commuting, pre-agreed appointments or arranging childcare for a specific time, often at short notice. Arranging, scheduling and providing childcare for on-call workers makes coordination of work and family responsibilities more difficult to sustain (Cherry, 2010; Harris, 2009). At the same time, fragmented and occasional work may perpetuate the gendered division of unpaid and paid work, instead of giving rise to questions about or challenges to such arrangements.

Platform work is not a systemic solution to gender inequalities in paid and unpaid work

While full autonomy with no time constraints or rules on working time and arrangements makes platform work sound appealing, the downside to such freedom creates an ‘autonomy paradox’ (Huws et al., 1996; Pérez-Zapata et al., 2016; Shevchuk et al., 2019). A high degree of autonomy and flexibility often leads to unsocial working hours (Ropponen et al., 2019). Platform workers often work unsocial hours (at evenings, nights or weekends) to optimise their income, match the time preferences of clients in different time zones or meet work–life balance challenges. (ILO, 2018c).

The same paradox applies to freelancers and independent contractors in general, and was pointed out long before platform work emerged (Huws et al., 1996). Self-employed translators who seemed to be fully autonomous found that they actually had little or no control over their workflow and that their working times were externally driven by deadlines set by their clients (Huws et al., 1996). In 2017, translation was one of the most female-dominated areas of platform work (JRC, 2018).

There is evidence that full autonomy of working arrangements leads to the highest degree of work-to-home spillover, higher even than for fixed and fully inflexible schedules. This is particularly true for men, mainly due to the increased overtime hours that men work when they have working time autonomy (Chung and Van der Lippe, 2018). People may set themselves unrealistic work schedules that lead to increased workload and eventually have negative consequences for work–life balance, health and well-being (Ropponen et al., 2019). There is a connection between working time and leisure time for recovery and sleeping. Keeping work and leisure time separate enables detachment from work during leisure time, which is important for recovery, particularly when the worker is highly stressed (Ropponen et al., 2019).

An ILO survey of workers performing online tasks via platforms found that women with young children (0–5 years) spend on average about 19.7 hours working on platforms in a week, while men with small children work over 30 hours. Of these women, 36 % work at night (10 p.m. to 5 a.m.) and 65 % work during the evening (6 p.m. to 10 p.m.); 14 % of women with young children reported working for more than 2 hours at night on more than 15 days in a month (ILO, 2018c). The proportion of mothers working evenings/nights is lower than for platform workers in general.

I haven’t really had a time when I rest. I don’t know what holiday means. ... I also work when I am travelling. It is just that if you have regular clients, you need to do everything in order to keep them. And if you don’t respond immediately to their emails then you can easily lose them. It is relatively harsh to be honest.

Source: Huws et al. (2019).

While platform work can improve work–life balance – especially for parents, other carers or those who face other obstacles to their full participation in the traditional labour market – it is necessary to ensure that it does not further polarise the labour market and marginalise these groups of people, pushing them into more precarious jobs. It cannot be seen as a substitute for proper support for carers or as a solution to the unbalanced division of care between women and men. It is important to point out that such arrangements – while being preferred and beneficial for some – may reinforce gender imbalances and inequalities in the labour market. Women who have heavy loads of care and other unpaid work take up ‘job bites’ around their care and home responsibilities, when in fact they would benefit more from proper care services and more balanced division of unpaid work at home. Work–life balance policies need to take this into account and provide comprehensive services and measures that support women’s participation in work, rather than relying on women to take odd jobs in order to earn some income alongside their unpaid work.