Women are more likely to have health limitations over their lifetime

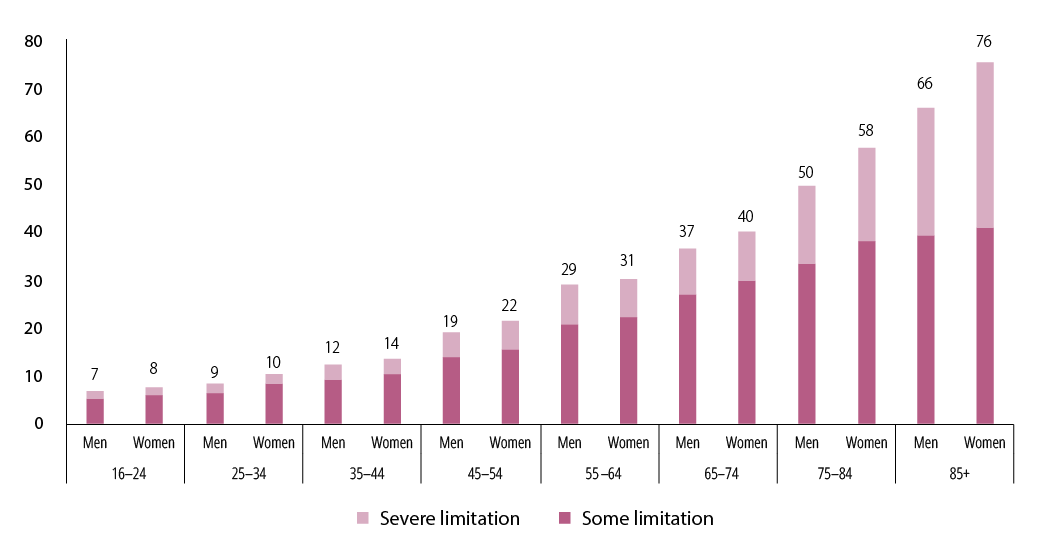

One in four adults in the EU reports that health problems affect what they can usually do[1], ranging from 9 % of people younger than 25 years to 40 % of those aged between 65 and 74 years. As health limitations increase with age and affect women and men differently, any analysis of ill health must consider age, gender and the severity of limitations.

Women suffer greater health limitations than men in all age groups (Figure 26). This is attributed to women being more likely than men to report symptoms of ill health. While normative masculinity is closely associated with physical strength and independence, seeking treatment and discussing symptoms is considered more socially acceptable for women.

Women are also affected by disabilities and chronic conditions from a younger age and to a greater degree than men (WHO and World Bank, 2011). Reasons include unmet needs for medical examinations, poor working conditions and low socioeconomic status, and gender-based violence (Garcia-Moreno and Watts, 2011; WHO, 2016d).

These factors help explain why gender differences in the extent to which health limitations affect daily activities are higher among older groups, to women’s detriment (Ogg and Rašticová, 2020). For example, among those aged 55–64 years, the proportion of individuals who report that everyday activities are limited by their health is only 2 p.p. higher among women than among men, at 31 % and 29 %, respectively Among those aged between 75 and 84 years, that difference rises to 8 p.p.: 58 % of women and 50 % of men.

The greater likelihood of women experiencing poor health is supported by data on healthy life years. Women and men in the EU can expect to be in good health until 65 and 64 years of age[2], respectively. However, as women tend to live longer, more of their life is spent in poor health – an average of 19 years, compared with 14 years for men[3] (Bambra, Albani, et al., 2020; EIGE, 2019c; WHO, 2016d, 2018b). While women appear to have a ‘mortality advantage’, it is offset by this higher morbidity (Bambra, Albani, et al., 2020; EIGE, 2019c; WHO, 2016d, 2018b), a phenomenon described by some as the ‘gender and health’ paradox (Bambra, Albani, et al., 2020; Doyal, 1995).

Gender differences across various indicators of self-reported health can also be accentuated by significant gender gaps in health literacy[4]. Several studies show that women are more likely to have general health knowledge and understanding, including of public health guidelines, common symptoms of specific health problems and their own health status (Baker, 2019). Lower levels of health literacy are associated with lower levels of information-seeking behaviours (Beck et al., 2014; Manierre, 2015; Nölke et al., 2015; Saab et al., 2018) and with men not seeking timely help for cancer symptoms (Baker, 2019; Fish et al., 2019).

Figure 26. Women and men limited in their usual activities because of health problems, by age group and level of difficulty experienced (%, EU, 2019)

NB: Data labels refer to the total percentage of women and men of each group reporting some or severe health limitations.

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/hlth_silc_06.