Men dominate technology development

Gender differences in digital skills and use of digital devices are gradually levelling out, particularly among young people. However, the lack of gender diversity in the workforce likely to invent, design, evaluate, develop, commercialise and disseminate digital services and goods remains striking.

Two aspects are particularly relevant to the contribution of women and men to the development of digital technologies and the gender dynamics at play in that sector: the gender make-up of people with STEM skills and qualifications, particularly in ICT[1], and the gender composition of the research and development (R & D) sector.

Aspirations for ICT careers are strongly gendered

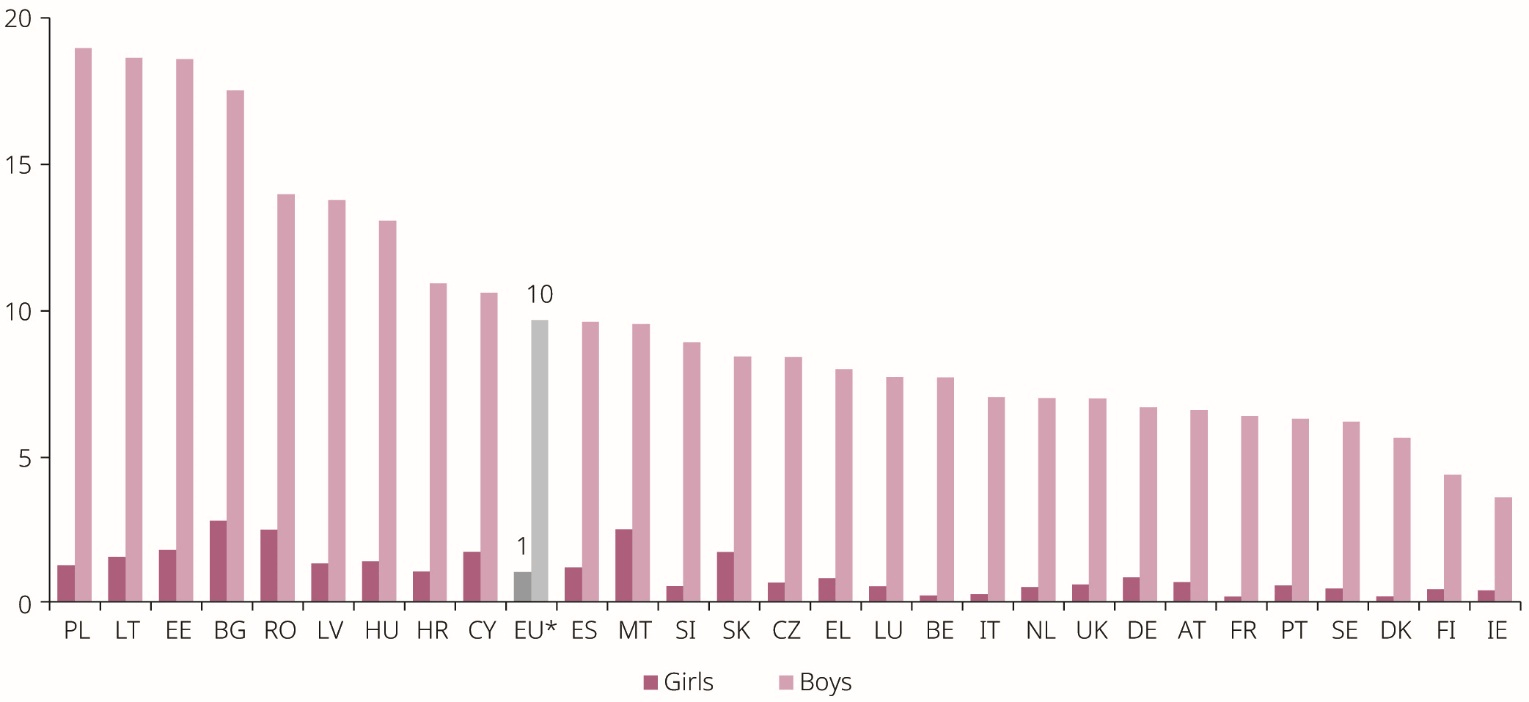

Gender attitudes to and confidence in digital skills and ICT are reflected in career aspirations, along with education choices. In 2018, only 1 % of girls, on average, reported that they expected to work in an ICT-related occupation, compared with 10 % of boys (Figure 35). In some Member States, including Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania and Poland, over 15 % of boys reported expecting to work in an ICT-related profession (OECD, 2019a).

Figure 35. Percentages of 15 year olds expecting to work as ICT professionals at age 30, by country and gender, 2018

While women outnumber men among tertiary education students (54 % compared with 46 %), they tend to be unequally represented across study fields, a phenomenon referred to as gender segregation. In 2018, only 17 % of female students had opted to enrol in STEM studies, compared with 42 % of male students.

As a result, STEM studies are largely dominated by male students (68 % versus 32 % of female students)[2]. Stark levels of gender segregation among STEM students and graduates lay the ground for future gender segregation in labour markets and subsequent gender disparity in the development of digital products, for example.

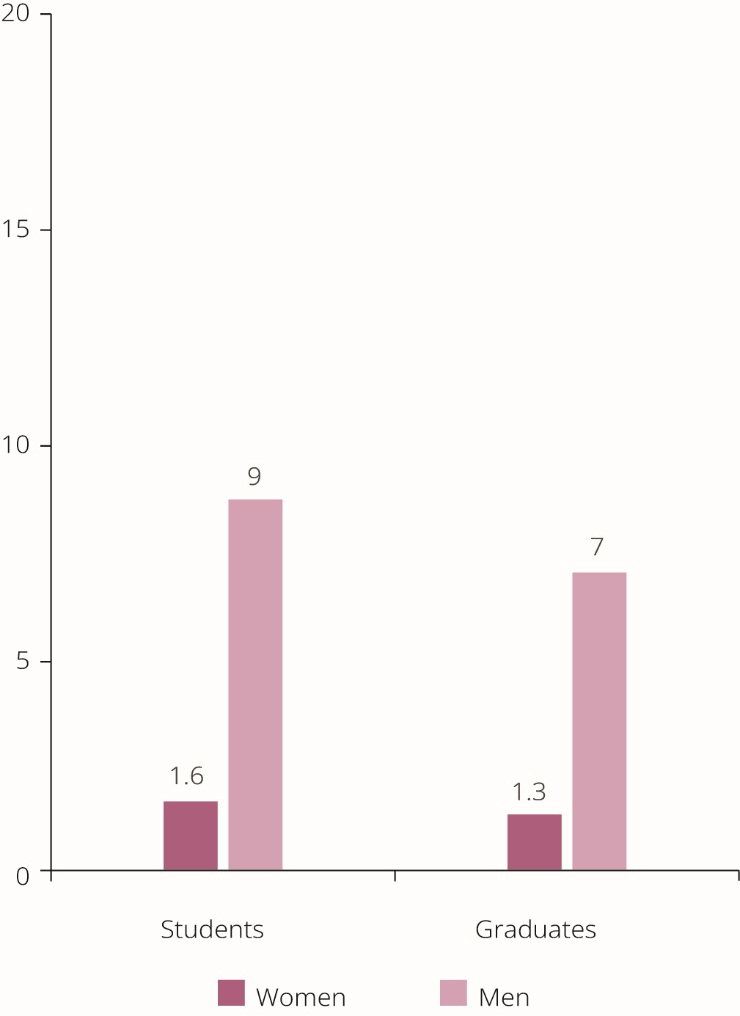

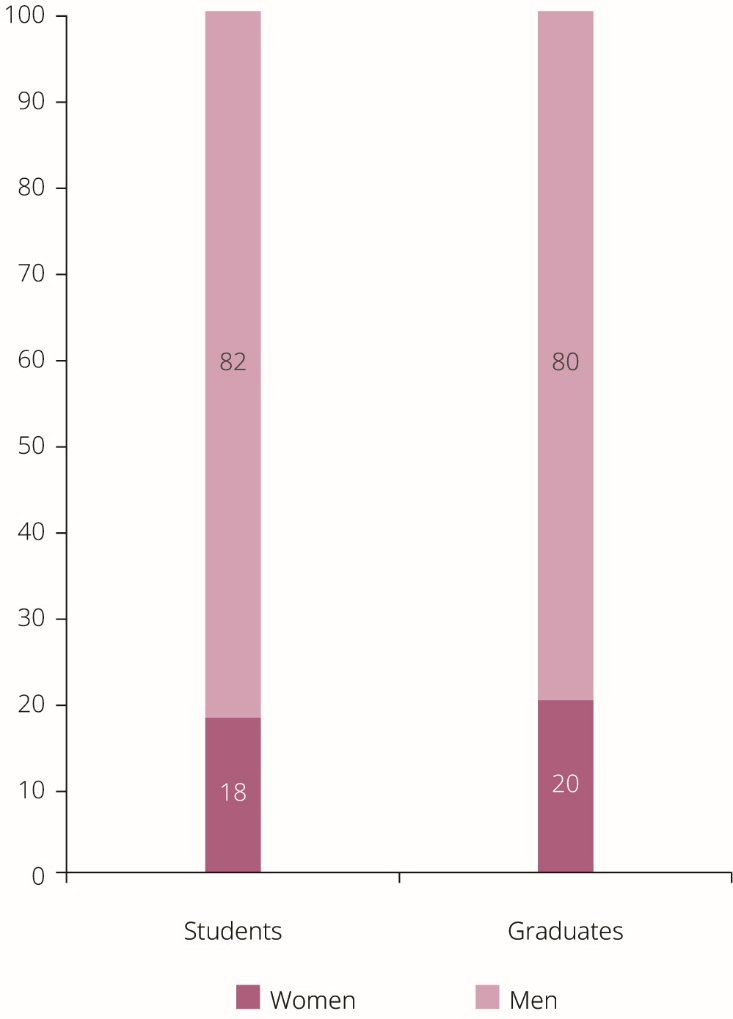

Although some STEM fields, such as natural sciences, mathematics and statistics, are quite gender-balanced, ICT is characterised by a high degree of gender segregation, with 82 % of students being male. In 2018, 9 % of male students chose to study ICT, compared with only 1.6 % of female students in the EU (Figure 36 and Figure 37). This level of under-representation of women among ICT students is hardly surprising, given the small number of young girls aspiring to become ICT professionals (Figure 35).

Women represent only 20 % of graduates in ICT-related fields, or 1.3 % of all women graduates from tertiary education, compared with 7 % of men graduates (Figure 36 and Figure 37).

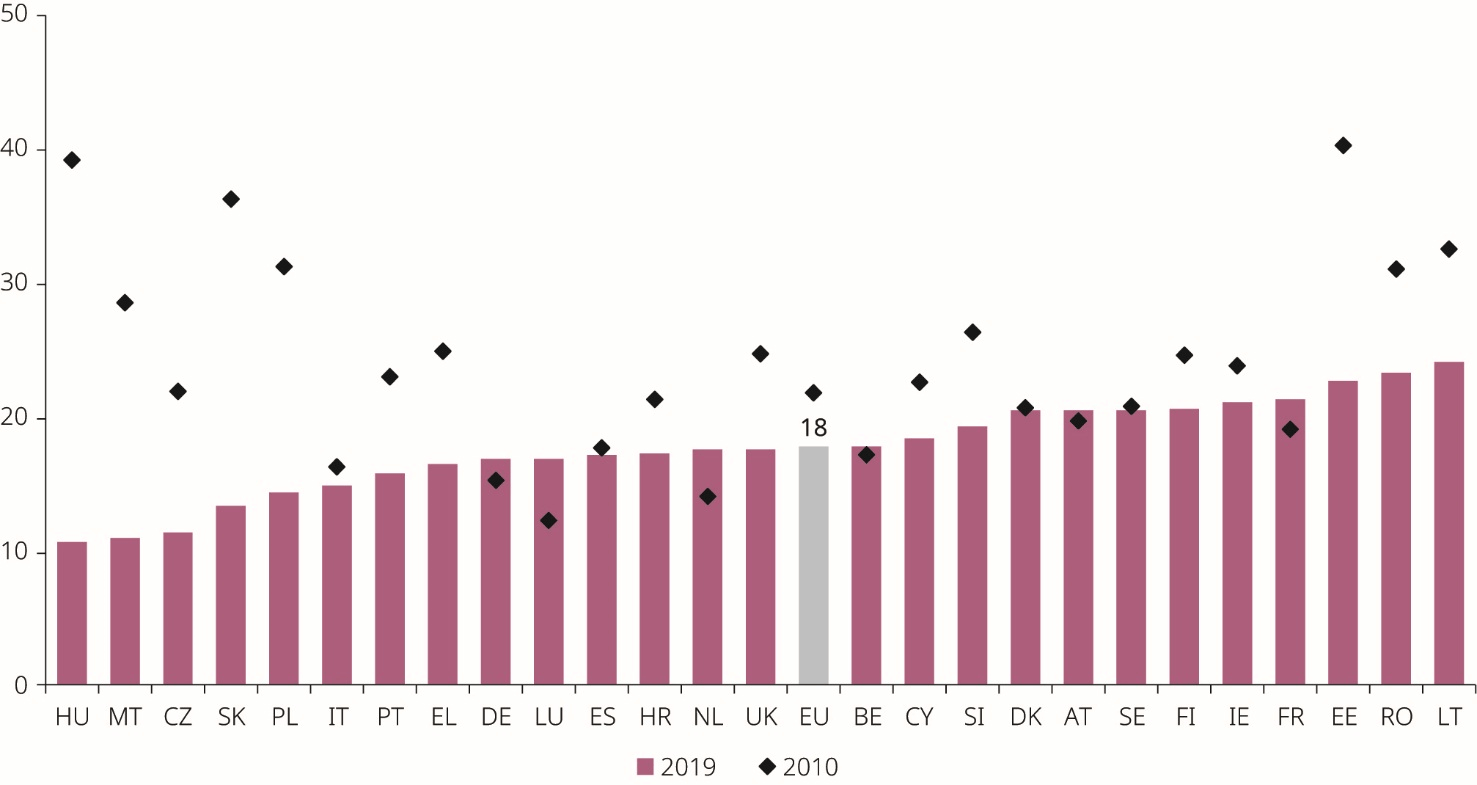

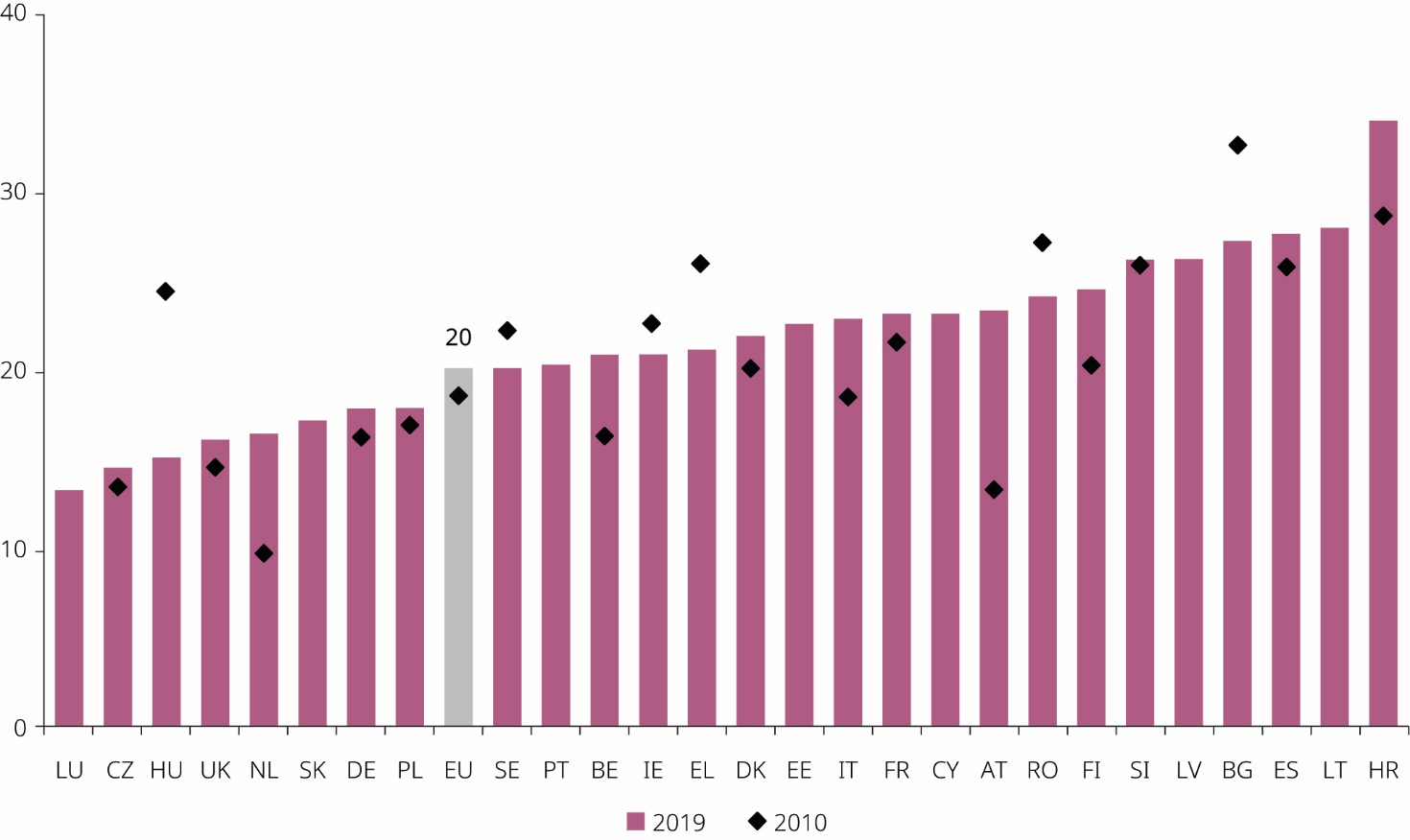

On average, over 8 in 10 ICT specialists[3] in the EU are men (Figure 38). Despite the overall growth of the ICT sector in recent decades, the share of women in ICT jobs in the EU has decreased by 4 p.p. since 2010, standing at 18 % in 2019. The high level of gender segregation in ICT jobs surpasses the gender imbalance in many other STEM jobs. For example, women represent about 27 % of science and engineering professionals in the EU[4].

Figure 38. Percentages of women among ICT specialists (aged 15 or older), 2010 and 2019

The data on entrepreneurship in the ICT sector points to even greater marginalisation of women. Only 7 % of self-employed ICT specialists with at least one staff member are women. Across all sectors, women entrepreneurs represent about 27 % of all self-employed people with at least one employee[4].

The gender gap in start-ups and venture capital investment is similarly striking. According to the EU Startup Monitor 2018, only 17 % of start-up founders are women. OECD analysis shows that women-owned start-ups receive on average 23 % less funding than men-led businesses (European Commission, 2018d). On a positive note, the OECD observes that venture capital firms with at least one woman partner are more than twice as likely to invest in a company with a woman on the management team, and three times as likely to invest in women CEOs (OECD, 2018a).

The evidence also shows that, despite the scarcity of women entrepreneurs, women-led digital start-ups are more likely to be successful than those owned by men (Roland Berger et al., 2017), while investments in female-founded start-ups perform 63 % better than investments with all-male founding teams (Marion, 2016).

Even though ICT skills are in high demand in the labour market (see subsection 9.2.2), women ICT professionals do not fare as well as their male counterparts. For women, the probability of being employed in the ICT sector following ICT-related studies is between 1 p.p. and 2 p.p. smaller than the probability of employment in a relevant field of women following other programmes of study (European Commission, 2016b).

EIGE’s research shows that only one third of recent STEM graduate women work in STEM occupations, compared with one in two recent STEM graduate men. Among vocational education graduates, the gap is more substantial, with only 10 % of women STEM graduates and 41 % of men STEM graduates working in STEM occupations. The majority continue on gender-segregated pathways, with 21 % of women with tertiary education working as teaching professionals and 20 % of women vocational education graduates working as sales workers (EIGE, 2018b).

Beyond ICT: women are under-represented in high-technology sectors

Beyond ICT, there are very few women scientists and engineers in the high-technology sectors likely to be mobilised in the design and development of new digital technologies. In 2019, across the EU, there were close to 32 million scientists and engineers employed in high-technology sectors[5], of whom only one fifth were women. That proportion has remained unchanged since 2010 (Figure 39).

Figure 39. Percentages of women among scientists and engineers (aged 25–64) in high-technology sectors, 2010 and 2019

A closer look at more specific technologies reveals even more striking gender gaps. For instance, only about 12 % of leading machine learning researchers are women (Simonite, 2018). The World Economic Forum, in collaboration with LinkedIn, found that out of 40 % of all professionals employed in software and IT services and who possess some level of AI skills, women make up only 7.4 %. Globally, only 22 % of AI professionals are women, a trend that has remained fairly constant in recent years (World Economic Forum, 2018).

R & D plays an essential role in the creation of new knowledge and finding practical applications for it in innovative processes and devices. Data from the OECD and the Joint Research Centre (JRC) shows ‘computers and electronics’ as the second leading sector in terms of R & D workforce globally, representing 367 companies and accounting for 13 % of R & D employees (JRC and OECD, 2019).

In addition, the IT services and telecommunications sectors accounted for 4 % and 3 % of that workforce, respectively[6]. Despite R & D’s importance for the development of digital technologies, little is known about the representation of women among R & D personnel and researchers in high-technology sectors of the business industry, especially ICT.

Patenting activity is one of the most observable outputs of the R & D process. Of the top 50 patenting companies globally, 24 were operating in the ‘computers and electronics’ sector (JRC and OECD, 2019). An analysis of outputs of the research process in terms of patents, trademarks and scientific publications highlights the persistent under-representation of women as contributors to research and innovation. Women account for approximately 9 % of European patent applications (European Commission, 2019h).

The extent to which women and men collaborate on innovative activities reveals a substantial gender gap. In the EU (2013–2016), the majority of inventors worked in all-male teams (47 %), with another 33 % of teams consisting of one male only inventor. Only 5 % of teams were gender-balanced, while teams composed entirely or mainly of women accounted for 0.7 % and 1.6 %, respectively (European Commission, 2019h). The compound annual growth of gender-balanced teams since 2005 stands at only 0.7 %.

The data shows that for the period 2013–2017, one of the lowest ratios of women to men (0.4) as contributing authors of articles was observed in the field of engineering and technology in the EU (European Commission, 2019h). On average, at the beginning of their careers, women tend to publish almost as frequently as men in their field, but, as seniority increases, male authors widen the gap and publish more often than their female colleagues. While this trend holds true for all R & D fields, it is accentuated in engineering and technology (European Commission, 2019h).

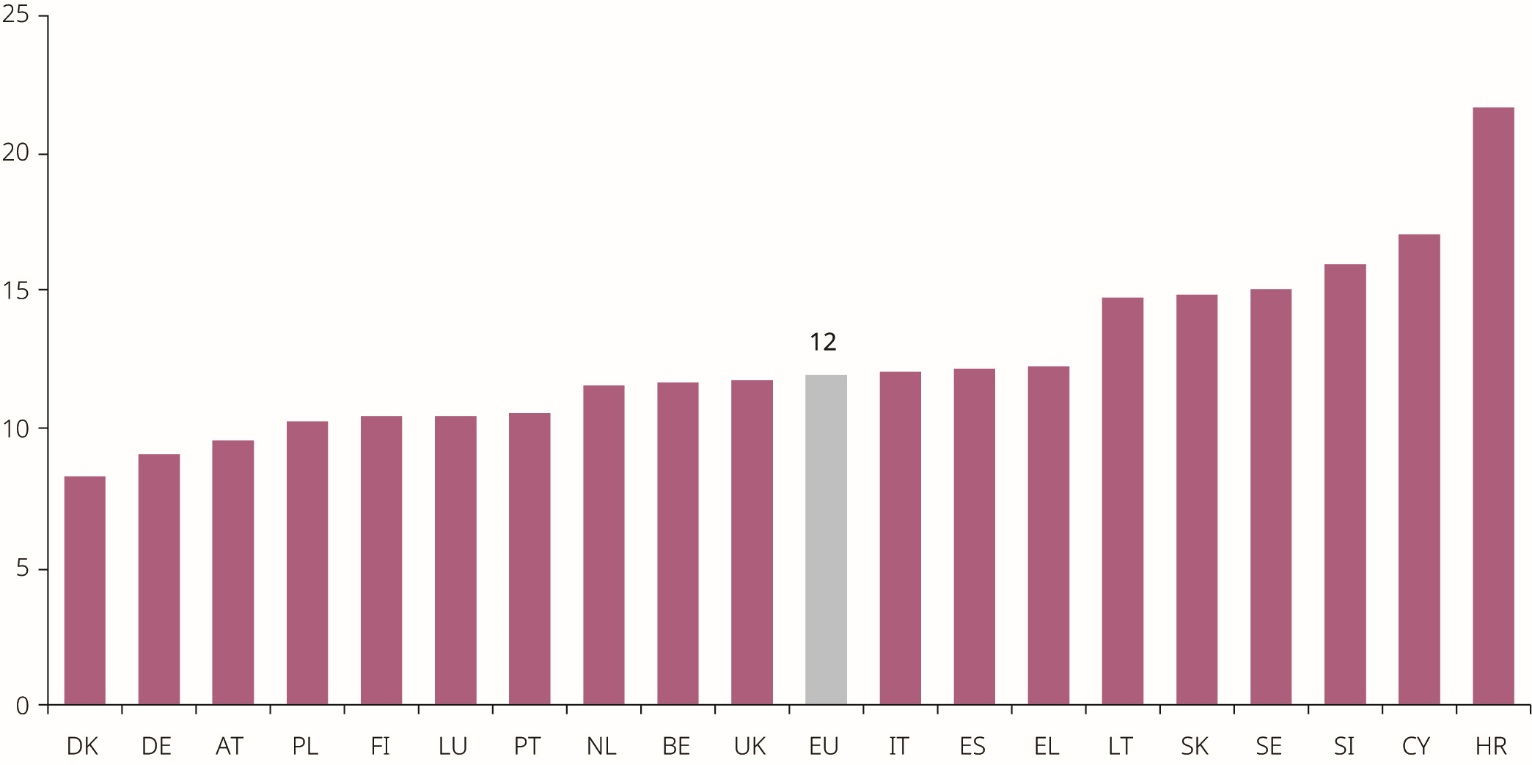

The low share (12 %) of women academics in engineering and technology points to the stark under-representation of women in decision-making positions (Grade A staff) in R & D functions (Figure 40).

Figure 40. Percentages of women among Grade A staff in engineering and technology R & D, 2016

While around half of research institutions in the EU have adopted a gender equality plan (European Commission, 2019h)[7], representation of women in decision-making positions in research still shows room for improvement. Men account for 78 % of heads of institutions[8], while boards of publicly funded research organisations have only 38 % women members[9].

The persistent gender imbalance among key decision-makers in large corporations remains a cause for concern. In 2018, 25 % of those in managerial positions in the EU ICT sector were women (17 % of chief executives were women)[10].

Across all economic sectors in 2020, the proportion of women on the boards of the largest listed companies in EU Member States has reached 29 %, but the top positions are still largely occupied by men, with women accounting for just 8 % of board chairs and 8 % of CEOs[11] (see Chapter 6, ‘Domain of power’). Women thus face a systematic disadvantage in taking up jobs with higher levels of responsibility.

At the same age, with the same or better education, and with the same family and other circumstances, women still have 25 % lower odds of progressing to higher profile jobs (European Commission, 2018c).

Many factors influence the persistent gender segregation in STEM and R & D jobs. These include gender stereotypes and the gender divide in digital skills and educational background, but also masculine organisational culture and a lack of work–life balance options and role models (Valenduc, 2011; Valenduc et al., 2004), (see subsection 9.2.4).

While data are scarce for the EU on the prevalence of sexual harassment in the science and technology sector, evidence from other parts of the world highlights systemic sexual harassment, which may discourage women from entering the sector or encourage their exit from it (National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2018; Seiner, 2019).