Domain of power

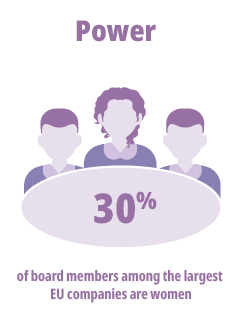

In terms of progress on gender equality in key decision-making positions in major political, economic and social institutions, the EU is only halfway towards equality (European Commission, 2021a). Although the domain of power has seen the most improvement of all domains since 2010, progress has been slow and uneven. Women account for only one in three members of EU national parliaments. Women remain substantially under-represented in corporate boardrooms: 30 % in 2021. In large companies, less than 1 in 10 board presidents or CEOs are women. Despite women’s growing involvement in research funding, media content and sports policies, their opportunities to influence decisions in these sectors remain limited.

There are many reasons for the systemic under-representation of women in decision-making positions. These include gender roles and stereotypes, the heavy burden of housework and care duties, which limits women’s ability to be active in public life, discriminatory employment practices and gender-based violence. Concerns are also mounting over rampant online harassment of women in leadership, which further discourages women from engaging in public debate or running for office (EIGE, 2020a).

The glaring absence of women in COVID-19 emergency decision-making is having a direct impact on people’s lives. Ensuring gender balance in decision-making on disease prevention and response in all countries can strengthen governments’ responses (OECD, 2020a). The benefits of gender balance in crisis management extend beyond the immediate consequences of the pandemic to the longer-term ramifications of COVID-19 on gender equality (EIGE, 2021c).

Political representation and access to decision-making are now more frequently included among social determinants of health (SDH) (Bhui, 2018; Gerry McCartney et al., 2021), and are sometimes referred to as a political determinant of health (Ottersen et al., 2014). A 2020 WHO report found that the gap in life expectancy is correlated with the degree of political equity, and the benefit was greater for men (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2020). In addition, Van de Velde et al. (2013) found that a high degree of macro-level gender equality, especially with more women in political decision-making, is associated with lower levels of depression in both women and men.

EU institutions have increasingly turned their attention to women’s representation in political and economic decision-making[1]. The European Commission brought the issue to the political fore in 2012. It proposed a directive to improve the gender balance among non-executive directors of listed companies, with a minimum target of 40 % of the under-represented sex. Since then, the directive has been blocked in the Council.

Gender balance in decision-making is one of the three main pillars of the EU gender equality strategy 2020–2025. It underlines the importance of having women in leadership positions across political, economic and social s (European Commission, 2020b). The Commission has also adopted the European democracy action plan. It envisages actions to mainstream equality at every level to better enable democratic engagement, including gender balance in politics and decision-making (European Commission, 2020a).