New forms of work and flexible working practices in the context of the ICT sector and platform work

For several decades, advances in digitalisation have been associated with two closely related processes: increased flexibility of work and the emergence of new forms of work. Increases in work flexibility date back to the 1980s, when the introduction of ICT transformed the world of work by enabling home-based and other forms of remote labour, such as teleworking (Huws et al., 1996).

In 2002, the European framework agreement on telework was negotiated by the social partners, establishing teleworking as a way for companies to modernise their work organisation and for workers to reconcile work with other aspects of their lives.

As the use of portable computers, tablets and smartphones spread throughout the labour market, and internet infrastructure and connectivity improved, a growing proportion of the workforce adopted flexible working patterns, working ‘anytime, anywhere’ (Eurofound, 2020b; Eurofound and ILO, 2017).

At the same time, the adoption of various remote working practices contributed to the emergence of new forms of work. The possibility to manage work remotely allowed employers to outsource and offshore an increasing amount (Rubery, 2015). This signalled a move away from the standard full-time open-ended contract with fixed working time towards less secure forms of employment situated within a ‘complex and multi-faceted network of relations between “independent contractors”, clients and intermediaries’ (Bergvall‐Kåreborn and Howcroft, 2014; Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2017; Rubery, 2015).

It led to increasingly fragmented nature of work, which was often broken down into ‘highly specified services and tasks’ to be delivered via ‘one-off contracts’ (Howcroft and Rubery, 2018). The past decade saw this process culminate in the emergence of platform work, which usually involves self-employed people working on multiple small-scale tasks mediated via online platforms, often alongside other, more stable jobs.

These changes can affect gender equality both positively and negatively. On the one hand, the increased flexibility of work is hailed as a promising way to support further participation of women and certain disadvantaged groups in the labour market (De Stefano, 2016; Overseas Development Institute, 2019), potentially leading to improvements in the Gender Equality Index domain of work.

This is because flexible working is often the only option for people to combine substantial unpaid care responsibilities (primarily taken on by women) with paid employment, and because it can encompass those who cannot work outside the home, such as people with certain disabilities.

More broadly, the increasing flexibility of work is seen as a way to improve work–life balance (see subsection 9.2.4) and potentially reduce gender inequalities in the distribution of unpaid work (and thus contribute to gender equality in the Index domain of time). On the other hand, some new forms of employment deprive workers of much of the traditional labour and social protections crucial for achieving gender equality (Howcroft and Rubery, 2018; ILO, 2018c; Overseas Development Institute, 2019; Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2017).

The remainder of this subsection examines the gendered consequences of changes in the form and flexibility of work enabled by digitalisation in two dynamic and growing segments of the economy: the ICT sector and platform work.

ICT jobs offer favourable working conditions but few women benefit

Newly emerging high-skilled occupations in the STEM and ICT sectors tend to offer somewhat safe and flexible working conditions, but few women have joined these sectors and benefited. The standard employment relationship is highly prevalent in ICT: 93 % of women and 88 % of men ICT specialists are employees; ICT workers are more likely to work a standard 40-hour week than the rest of the working population; and few have temporary work contracts (8 % of women and men)[1].

Only 7 % of women and 12 % of men in ICT are self-employed, which are lower proportions than for other occupations (10 % of women and 18 % of men[2]. Evidence from the literature suggests that women and men tend to choose self-employment for different reasons. Women are more likely to opt for it because of the potential for better working time flexibility, work–life balance and opportunities to combine care and work responsibilities, while men are more likely to be self-employed for career-related reasons, such as to control their own work or to earn more money (IPSE, 2019).

Despite the rather standard form of employment, teleworking and mobile working arrangements are highly prevalent in the ICT sector, especially among the self-employed, indicating a high degree of flexibility in working arrangements in this sector (Eurofound, 2020c).

ICT jobs generally offer favourable working conditions: they are relatively well paid, require less work during atypical working hours, and give workers considerable flexibility and autonomy to arrange their working time (EIGE, 2018d). For instance, 83 % of women and 80 % of men in ICT find it very easy or fairly easy to arrange an hour or two off during working hours to take care of personal or family matters.

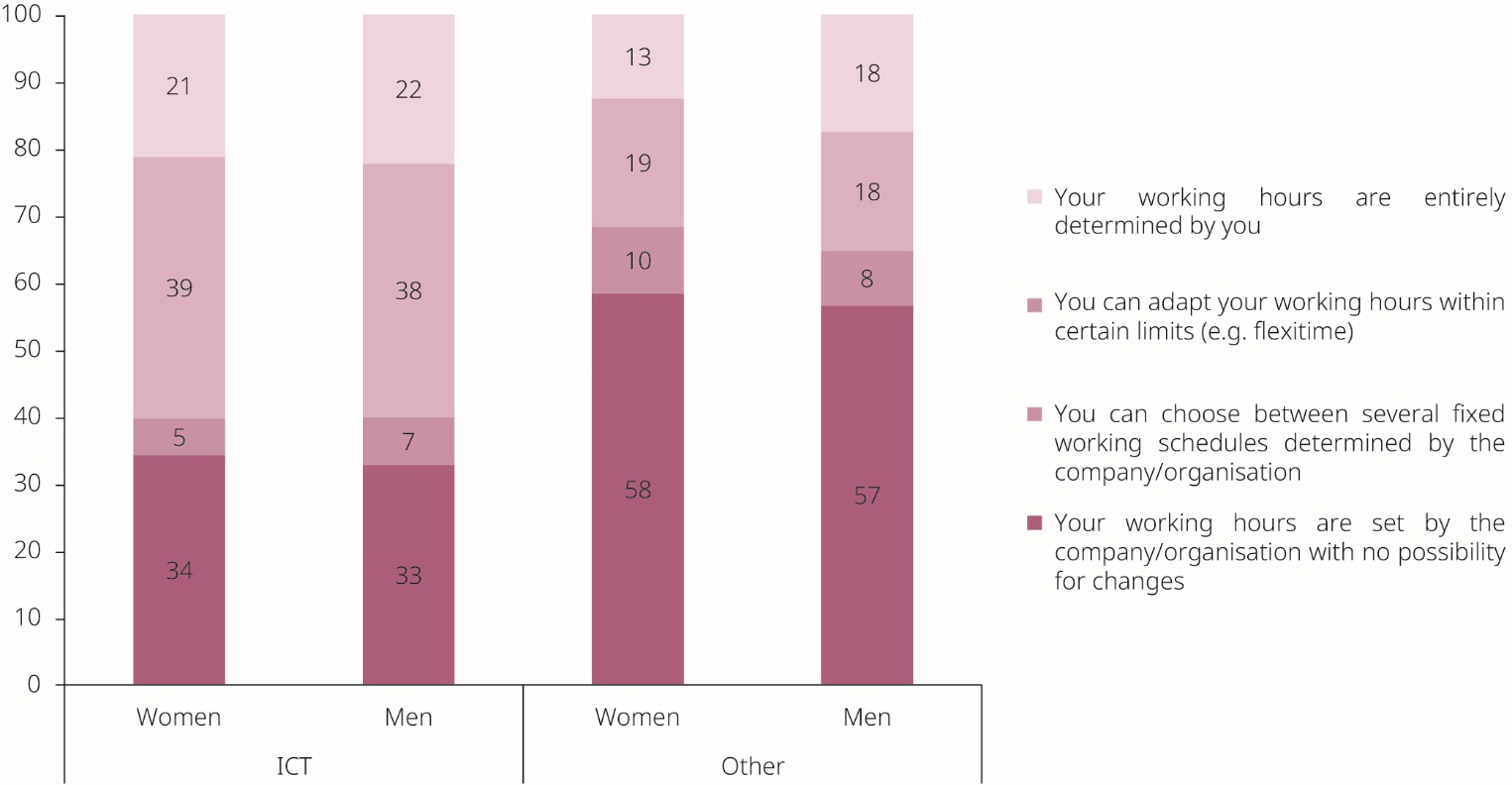

There is also significant overall working time autonomy. Only one quarter of ICT sector employees have their working time arrangements strictly set by the company with no possibility for change (compared with almost 60 % of the rest of the working population). The remaining ICT sector employees enjoy various amounts of flexibility or even full autonomy (Figure 46).

Figure 46. Percentages of women and men (aged 20–64) in ICT and non-ICT sectors, by working time arrangements, EU, 2015

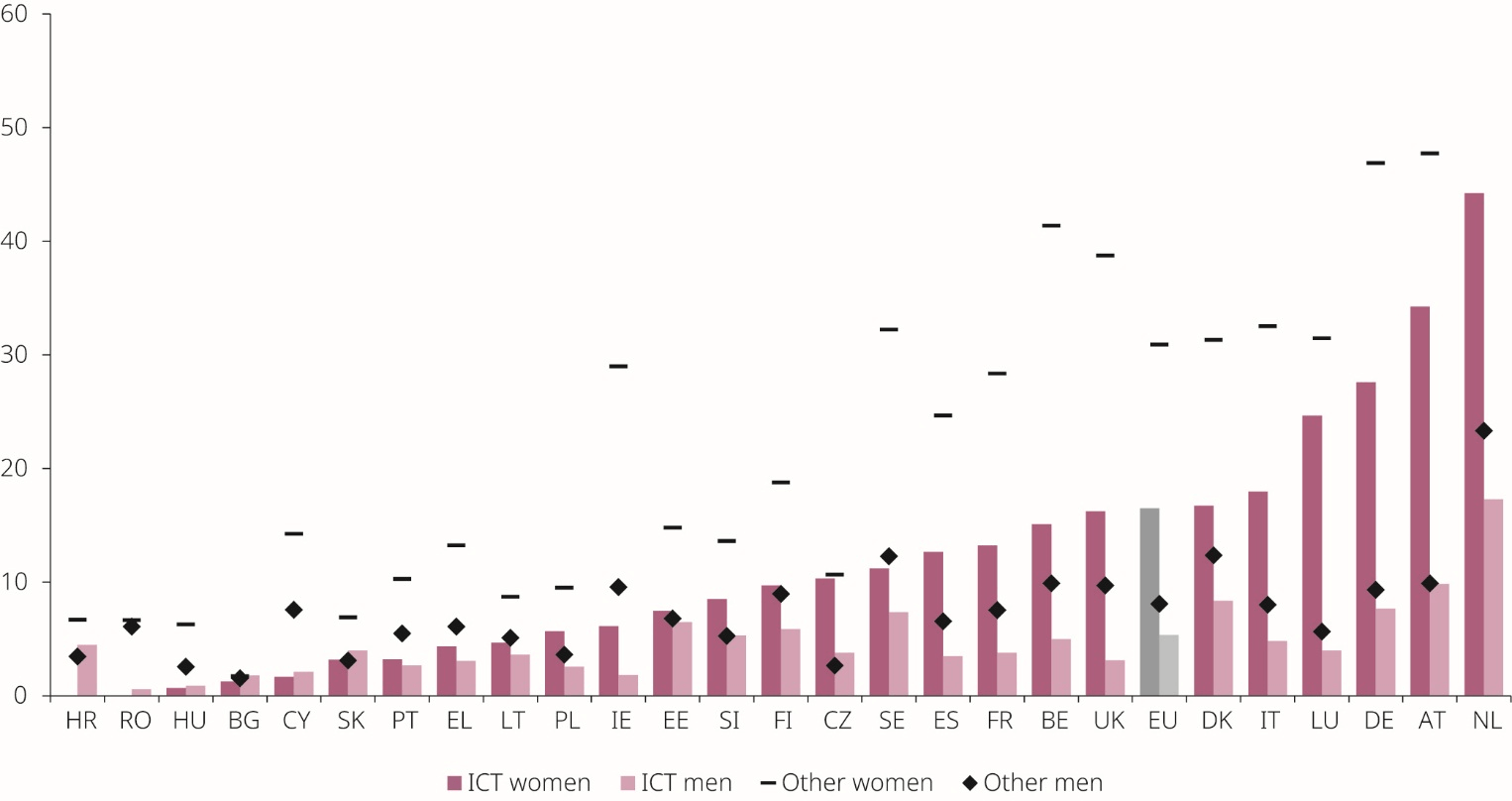

However, part-time work – which, in some cases, facilitates a better work–life balance – is less common among ICT specialists than in other occupations in many Member States, suggesting lower availability (i.e. owing to a shortage of ICT specialists) or lower need (i.e. many employees forgo care duties). In ICT, 17 % of women and 5 % of men work part-time (Figure 47), compared with 31 % of women and 8 % of men in other occupations.

Around two thirds of women in ICT jobs work part-time because of their care responsibilities, while only one quarter of men choose to work part-time for this reason (EIGE, 2018d). As with self-employment, women and men are likely to use their control of their working time differently: women tend to use it to achieve a better work–life balance, while men use it to increase their work commitments (Hofäcker and König, 2013).

Platform practices that restrict worker autonomy can reduce women’s participation

Platform work can be an opportunity to increase the participation of women in the labour force (De Stefano, 2016; Overseas Development Institute, 2019). It can offer workers considerable autonomy in terms of their workplace and schedule, including the freedom to choose which tasks they do, their working time, and how to organise and perform their work (Eurofound, 2018b). This can benefit women in particular, supporting them to combine work with their disproportionate share of care and family responsibilities.

However, the autonomy and flexibility of platform work varies significantly depending on the type of service provided and the work management practices of individual platforms (Eurofound, 2018b; ILO, 2018a). Representation of women and men varies across the different types of services and platforms (see subsection 9.2.2), and their degree of autonomy is likely to do so as well.

For example, men currently dominate the provision of certain platform services associated with higher work autonomy, such as software development. Other workers are likely to face platform practices that impose a combination of low work/lack of pay security and limited work autonomy. This may well put people with significant caring and family responsibilities at a disadvantage and is likely to have negative consequences, particularly for women’s participation.

Some examples are provided below to better illustrate the variation in work autonomy for different types of platform work and its gendered implications.

Gendered consequences of platform practices that limit worker autonomy

Example 1. Ride-hailing platforms, such as Uber, often exert considerable control over their workers to ensure the immediate availability of their services to customers. They commonly retain the power to set prices for rides and can use this to influence workers’ driving patterns by applying price surges to periods and places of high demand (ILO, 2018a).

In some cases, they use worker-monitoring systems to promote immediate availability among drivers: drivers who decline or cancel ride requests face the risk of deactivation (i.e. employment loss). In other cases, they encourage longer availability of drivers on the platform (e.g. rewards for a certain number of trips in a day), even though this leads to longer periods of (unpaid) waiting for rides.

Gendered consequences. Such practices do not favour combining (well-paid) ride-hailing work with caring responsibilities and may help to explain the gender pay gaps (Cook et al., 2018) and employment gaps (Huws et al., 2019; JRC, 2018) in ride-hailing services.

Example 2. Platforms focusing on small online tasks (clickwork, such as in Amazon Mechanical Turk), tend to grant workers more autonomy in terms of their work schedule and place. However, they still adopt practices that favour workers who work longer, without interruption and on demand (Adams and Berg, 2017). They usually gather online tasks from clients and invite workers to bid for these.

The tasks often need to be completed quickly and are posted at ad hoc times that suit clients. This requires workers to spend unpaid time searching for tasks and to then bid for them quickly once they are available (ILO, 2018c). Platforms sometimes monitor whether workers work without interruptions, for example by taking screenshots of workers’ screens or recording keystrokes and mouse clicks (ILO, 2018a).

Gendered consequences. Such working patterns are not suitable for women who wish to combine platform work with care responsibilities, and are likely to contribute to the gender pay gap (Adams and Berg, 2017).

Platform workers may face discrimination and harassment in some settings

Work-related discrimination in the highly diverse platform economy is a complex, multifaceted topic, with outcomes often heavily dependent on the type of service provided and the workforce practices of a given platform. Nevertheless, several broad points emerge from the literature and are reviewed here. This is not intended as a comprehensive review but, rather, an illustration of ways in which platform work can foster or constrain discrimination based on gender or other grounds.

Firstly, platform work poses challenges for the application of the EU’s gender equality and non-discrimination legislation, making it difficult for platform workers to prove discrimination on gender or other grounds. This is primarily due to the fragmentation of work into small tasks performed for different clients on an irregular basis (Countouris and Ratti, 2018). Such fragmentation makes it difficult to identify comparable workers or the sources of discrimination when dealing with discrimination claims[4].

Secondly, to the extent that platform work enables anonymous interactions between workers and clients in virtual settings, this can help to reduce discrimination based on individual worker characteristics such as gender or ethnicity (De Stefano, 2016; Eurofound, 2019).

However, many platforms regularly publish workers’ personal information online, including name, age, gender and photo. Where such information is available, it allows people to make decisions reflecting their own personal biases based on gender, ethnicity or other grounds (Rosenblat et al., 2017; Schoenbaum, 2016). One United States-based study found, for example, that Airbnb hosts from Asian backgrounds were found to earn 20 % less than their white counterparts.

In some cases, platforms may even promote or enforce certain discriminatory choices by design and use sexist advertising. For example, Lyft began as a ride-sharing service for women only, and in 2014 Uber ‘offered a promotion in France for rides with “Avions de Chasse” (“hot chick” drivers) with the tagline “Who said women don’t know how to drive?” ’ (Schoenbaum, 2016).

Platform workers often lack access to key social and work protections, including parental leave

Owing to the fragmented nature of their work and their self-employed/independent contractor status, many platform workers lack access to key social and work protections. While eligibility varies considerably by Member State, a substantial share of platform workers have little or no access to sickness and healthcare benefits, unemployment benefit, paid holiday entitlements, insurance against work-related accidents and illnesses, old-age and disability benefits, and maternity and paternity benefits (Eurofound, 2018d; European Commission, 2019a; ILO, 2018c; Overseas Development Institute, 2019).

This is an issue especially for those platform workers who do not combine platform work with other employment that provides them with access to social and work protections. While there are no comprehensive, gender-disaggregated data on platform work as a sole source of employment, it may well be that this is a more common situation for women than men.

For example, men providing online services via platforms are more likely to do so to top up income from other work than women (Adams and Berg, 2017). For a notable share of platform workers, social protection coverage is ensured through their main jobs in the traditional economy, but here women are observed to have less social insurance coverage than men (Behrendt et al., 2019).

The lack of access to social protection linked to childbirth and childcare has a particularly strong gender dimension, as it limits women’s ability to stay in employment and prevents more equal sharing of unpaid care responsibilities. According to a study by the European Commission (2015), only around half of self-employed women aged 15–49 were entitled to maternity benefits.

EIGE’s study on eligibility for parental leave (EIGE, 2020c) similarly found that in a number of Member States access was lacking among people who were self-employed or without a stable employment relationship. Access to some other benefits is also likely to have a gendered dimension.

For example, women’s lack of access to old-age and disability benefits may be particularly problematic, as they tend to live longer and to spend more years living with disabilities (EIGE, 2020a).

Weak collective representation of platform workers can increase gender-based pay inequalities

Representation of platform workers by trade unions is generally weak, although there are now some examples[11] of trade unions representing or supporting platform workers at Member State level (Eurofound, 2018d)[12]. Less formal worker-organised initiatives seem much more common (Eurofound, 2018d; ILO, 2018a)[13]. One of the key obstacles to platform workers joining or organising unions is the fact that they are self-employed and are, therefore, excluded from the right to collective bargaining in some jurisdictions (Eurofound, 2018d).

Another complication is the piecemeal structure of platform work, which often relies on isolated workers with very limited communication with one another (Eurofound, 2018d; ILO, 2018a). Finally, the lack of job security is likely to inhibit workers’ efforts to organise, as platforms often reserve the right to terminate workers’ access to the platform without giving a reason (Eurofound, 2018d; ILO, 2018a).

Poor union coverage of platform workers is likely to have gendered consequences, for example in terms of pay. This is because women generally fare poorer in settings that rely on individual negotiations when it comes to pay (see subsection 9.2.5) (Barzilay, 2018; Barzilay and Ben-David, 2016; Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2017). Lack of worker representation can make it more difficult to resist exploitative practices by platforms that limit worker autonomy and flexibility (ILO, 2018a), in turn making platform work less attractive for people (mostly women) with significant caring responsibilities.

Platform work in the care sector: opportunities and challenges

Platform work in the care sector has the potential to provide new solutions to some of care work’s long-standing problems. In fact, platforms act as intermediaries, matching demand and supply more efficiently, minimising geographical distance and allowing both parties to select flexible working arrangements (Trojansky, 2020).

Platform work offers new opportunities for the provision of home-based care, which has become a priority in the process of ‘deinstitutionalisation’ in the EU (EIGE, 2020e). At the same time, however, platforms alone cannot solve the vulnerability of care professionals, or adequately address their disadvantaged working conditions (Ticona and Mateescu, 2018b).