Job automation, use of new technologies and transformation of the labour market

Much of the current policy debate about the future of work centres on the increased use of digital technologies and their capacity to replace or complement workers in an ever-broadening range of tasks. The spread of new technologies is often seen as a way to increase the productivity and competitiveness of the EU economy.

Notably, a range of time-consuming or physically demanding routine tasks have proven feasible to automate (JRC, 2020b), enabling some workers to focus on more creative aspects of their work, increasing added value and – in some cases – leading to improvements in working conditions (Eurofound, 2018c; JRC, 2019a).

However, technological progress also has the potential to be highly disruptive, as many jobs need to be reorganised and technology will completely replace workers in some instances (Eurofound, 2020a).

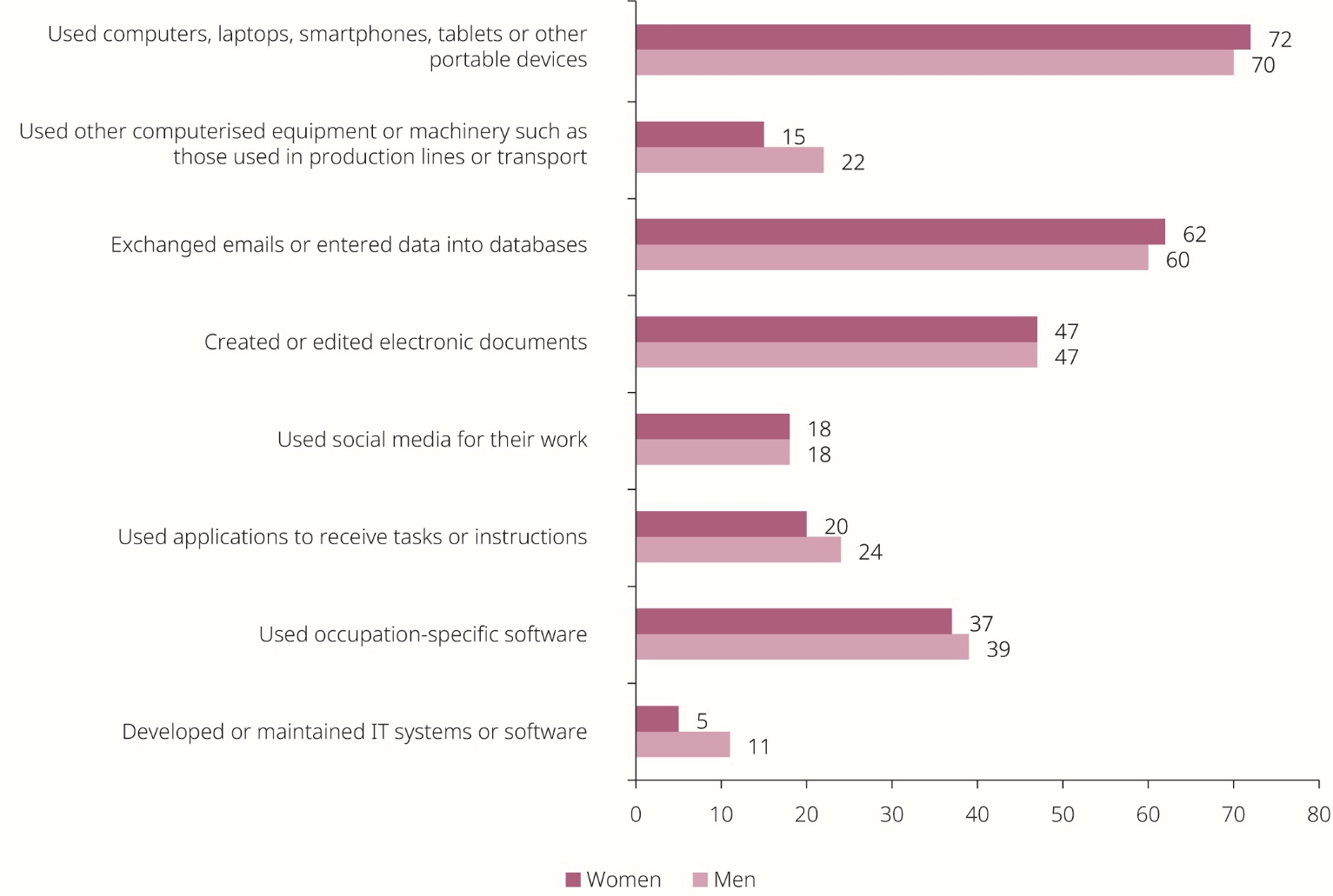

While digital technologies have transformed the majority of workplaces in the EU labour market, gender differences in the use of ICT at work persist. Eurostat data show that 71 % of those in employment[1] use computers, laptops, smartphones, tablets or other portable devices at work, with the proportion reaching 95 % in some sectors[2].

The past 5 years have seen the use of digital technologies increase in almost 9 out of 10 workplaces in the EU (European Commission, 2016b). Yet women continue to use some digital technologies less frequently than men (Figure 41), which is likely to limit their employment prospects in jobs that depend on the use of such technologies.

Figure 41. Use of ICT at work and activities performed by women and men (aged 16–74) in the EU (%), 2018

Earlier estimates predicted that digitalisation could lead to alarmingly high rates of job loss due to automation in the next decade or so (Frey and Osborne, 2017; World Economic Forum, 2016), but these have since been tempered by more modest estimates for OECD economies of 10–20 % of jobs at risk (International Monetary Fund, 2018; OECD, 2016; PwC, 2019).

Increasingly, it looks like many jobs will be transformed rather than fully automated, with workers switching to tasks that complement new technologies from tasks that are being replaced by them (Autor, 2015; European Commission, 2019e). Some entirely new jobs (or jobs transformed so profoundly as to effectively constitute new jobs) are also likely to appear (Eurofound, 2020a), for example in the STEM sector.

Women face slightly higher risk of job loss due to automation

Women are usually reported to be at a slightly higher risk of job loss due to automation than men (International Monetary Fund, 2018; OECD, 2016; PwC, 2019). A recent International Monetary Fund (2018) study on the gendered impacts of automation found that around 11 % of employed women were at risk of job loss, compared with 9 % of men. This gap seems to be driven by significant differences in a few countries (e.g. Cyprus and Austria), while others show little or no difference (e.g. Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France and the United Kingdom).

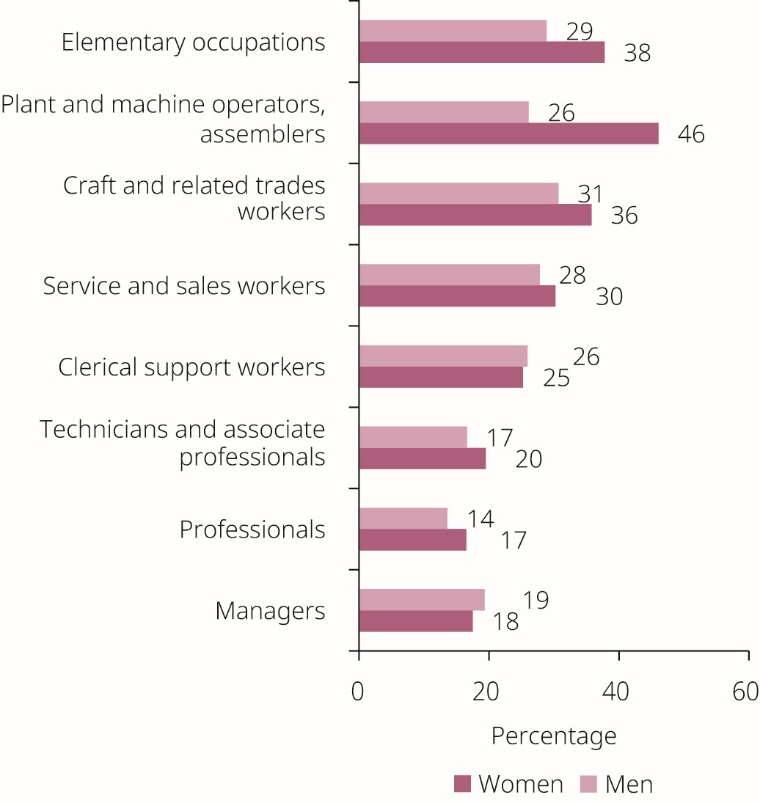

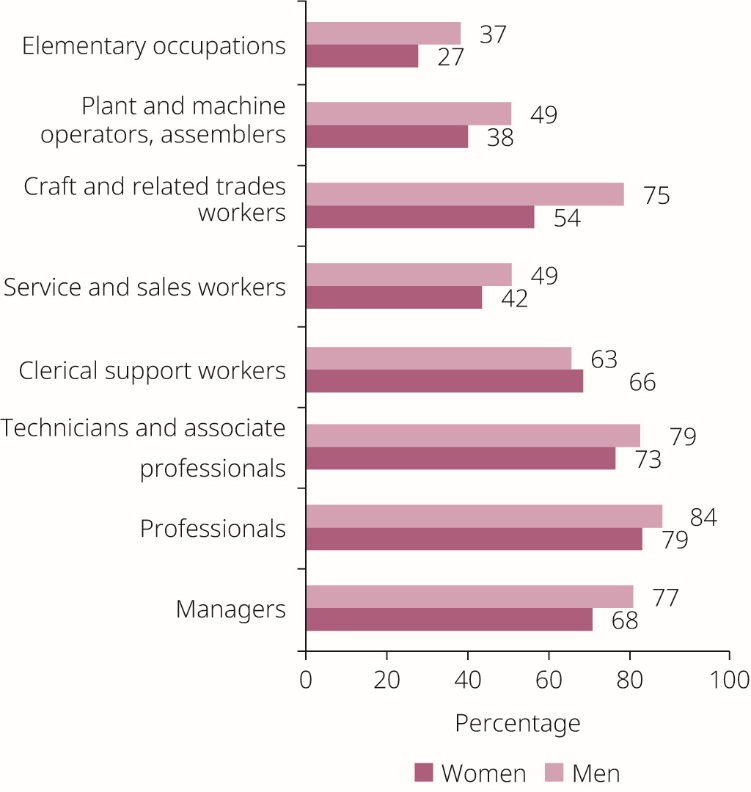

The higher risk of automation for women relates to gendered differences in work content; in the EU, women across different occupational categories are somewhat more likely to undertake routine, repetitive tasks and less likely to undertake complex tasks (Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2017) (Figure 42 and Figure 43).

Another study (Lordan, 2019) also suggests that women are more vulnerable than men to automation in some countries (Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Hungary, Austria, Finland and the United Kingdom), whereas they face the same risks in others (Greece, France, Croatia, the Netherlands and Slovenia).

Figure 42. Percentages of workers undertaking repetitive tasks of less than 10 minutes’ duration, by sex and occupation, EU, 2015

Figure 43. Percentages of workers undertaking complex tasks, by sex and occupation, EU, 2015

In addition to being more exposed to the dangers of automation, women may also benefit less from the resulting changes in income distribution. Automation is likely to be a capital-intensive process, relying on increasing use of new technologies and thus particularly benefiting owners of capital. Using data from advanced economies, similar technological changes have been linked to a decreasing share of national income flowing to workers (Dao et al., 2017).

Instead, income is likely to flow to owners of capital (Dao et al., 2017), who typically hold that capital indirectly through a range of financial products, such as stocks or shares (IPPR, 2019). This financial wealth tends to be highly concentrated among the wealthiest individuals, and among men in particular; there are sizeable gender gaps in financial wealth among the top 5 % of wealthiest individuals in a number of EU Member States (Schneebaum et al., 2018).

Automation is likely to affect both female- and male-dominated occupations

The slightly higher overall risk posed by automation to women conceals considerable variation in how different occupations (and sectors) will be affected. Digitally enabled machines are likely to replace human labour, particularly in routine, easily codifiable tasks (Autor, 2015; Frey and Osborne, 2017; Lordan, 2019), the distribution of which varies considerably across occupations (Figure 42 and Figure 43).

Less predictable tasks, such as abstract thinking or unstructured social interactions, are proving more difficult to automate, leaving some occupations at a much lower risk of automation than others (Autor, 2015; Frey and Osborne, 2017; Lordan, 2019).

Historically, automation was linked to elimination of clerical jobs and reduced availability of jobs in the retail and financial service sectors that, up to that point, had provided an expanding field of employment for women (Huws, 1982). At the same time, technological change began to de-skill many traditionally ‘male’ jobs (Cockburn, 1987), opening them up to women with newer technological skills. This renewed interest in the statistical analysis of occupational segregation by gender.

Research was carried out to identify horizontal and vertical patterns of segregation by occupation and industry, such as the concentration of women and men at different levels in organisational hierarchies (Rubery, 2010), and to identify ways in which new kinds of technology-enabled work reproduced and expanded dominant patterns of gender segregation and inequality (Howcroft and Richardson, 2009).

Highly educated women often enter new jobs that are difficult to automate

While women face a somewhat higher risk of automation based on current employment patterns, there are signs that the structure of women’s employment is changing, with high-skilled work increasingly prevalent.

Women’s educational attainment has grown rapidly and many education gender gaps that existed in the past have already been eliminated, as can be seen from the Gender Equality Index scores in the domain of knowledge. Women have begun to take most of the new high-skilled jobs[3] that are unlikely to be automated in the near future: around 8 million of the 12 million high-skilled jobs created between 2003 and 2015 in the EU went to women (OECD, 2017a).

This led to an ‘upgrading in the female occupational structure, with the share of women in high skilled occupations … increasing’ (Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2017, p. 7). This does not, however, mean that women are paid equally to men in these jobs.

The fact that women have, on average, lower wages than men may affect the patterns of automation (Rubery, 2018). Firstly, the low-paid nature of certain female-dominated occupations (e.g. domestic work) may slow down the pace of digital innovation, since such innovation can be, at least initially, quite costly and may not always pay off when labour costs are low (Rubery, 2018). This may protect some women from job loss at least in the short term, although it brings little prospect of better pay or working conditions.

Secondly, since women tend to earn less than men in the same occupations, this may provide them with new opportunities when male-dominated occupations become reorganised or restructured as a result of automation. In such cases, employers may favour hiring women into new positions because of their lower salary demands.

Based on previous experience, this often results in ‘first a period of desegregation of male-dominated jobs, followed by either the feminisation of the whole occupation or the emergence of new feminised subdivisions within the occupation’ (Rubery, 2018). In the service sector, for example, programming tasks that were well-paid and highly skilled in the recent past may become ‘feminised’ – although more women are recruited, they continue to be treated as ‘secondary earners’ and their wages drop (Howcroft and Richardson, 2009).

Thus, efforts to ensure equal pay for equal work will be needed if women are to fully benefit from such new opportunities.

Potential of job automation to improve gender equality

Scenario 1 – Index domain of work. Transformation of the labour market structure offers an opportunity to change established gendered patterns of employment, especially in the context of the rapid growth of women’s skills (IPPR, 2019; Rubery, 2018). However, evidence from the past decade shows little – if any – progress on the desegregation of the EU labour market (Piasna and Drahokoupil, 2017). Jobs within the STEM and ICT sectors are a stark example of this lack of progress (see subsection 9.1.3).

Scenario 2 – Index domain of time. Potential job loss due to automation has sparked debates about more balanced distribution of paid and unpaid work among women and men (Howcroft and Rubery, 2018; IPPR, 2019; Rubery, 2018). If machines replace a significant share of human work input, this may reduce the overall amount of jobs available. To better distribute the remaining work, proposals to reduce the duration of the working week are frequently discussed, with potential positive outcomes for gendered division of unpaid work. In this context, the recognition of women and men as equal earners and equal carers across the life cycle will be important.

Scenario 3 – Index domain of money. Automating some routine tasks can free up more time for tasks requiring interpersonal, creative or advanced ICT skills (Howcroft and Rubery, 2018; IPPR, 2019). This is an opportunity to upskill certain low-paid jobs held by women and perhaps even achieve higher wages and reduced pay gaps.

The potential of automation to challenge existing gender inequalities remains unclear

Given the uncertain nature of changes in technology and gender relations, it is difficult to go beyond stylised lists of factors likely to influence the gender equality outcomes of automation in the future. The current literature mostly limits itself to speculating about the ways in which this process could affect gender equality, namely gender segregation, division of unpaid work, pay gaps and working conditions.

All of these speculative scenarios have something in common: the changes have the potential to improve gender equality but their outcomes are highly uncertain and there is no guarantee that their promise will be fulfilled. Indeed, the research reviewed (Howcroft and Rubery, 2018; IPPR, 2019; Rubery, 2018) suggests that this is unlikely to happen without (1) gender-sensitive regulation, institutions and policies; (2) challenges to established gender stereotypes, such as those relating to ICT and STEM participation and caring activities; and (3) greater representation of women in key decision-making positions.