Country information

Description

Progress on gender equality in Netherlands since 2010

With 74.1 out of 100 points, the Netherlands ranks 5th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. The Netherlands’ score is 6.2 points above the EU’s score. Since 2010, its score has increased by only 0.1 points. There has been a bigger increase since 2017, with an extra 2.0 points gained. The Netherlands’ ranking has dropped by two places since 2010.

Best performance

The Netherlands’ scores are the highest in the domains of health (90.0 points) and money (86.2 points). With 83.9 points, the Netherlands ranks 2nd in the domain of time.

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities are most pronounced in the domains of power (57.2 points) and knowledge (67.3 points), although these are among the highest scores in the EU (ranking 9th and 7th).

Biggest improvement

Since 2010, the Netherlands’ score has improved the most in the domain of work (+ 1.5 points), with no change in the ranking. Since 2017, it has gained 7.2 points in the domain of power.

A step backwards

The Netherlands’ scores have decreased in the domains of time (– 2.0 points), money (– 0.4 points) and health (– 0.3 points). In the domains of money and power, its rankings have dropped by seven and five places, respectively.

Key highlights

Positives

- The shares of women among the board members of the central bank and on the boards of the largest quoted companies have increased.

- The share of women ministers has increased.

- Unmet needs for medical examination have decreased, from a little over 1 % in 2010. In the area of access to health services, the Netherlands ranks 1st in the EU.

Negatives

- Women earn less than men and the gender gap in earnings has slightly increased, from 20 % in 2010.

- The shares of women and men at risk of poverty are increasing. Lone mothers face an even higher risk of poverty (29 %).

- Around 2 % of women and 3 % of men with disabilities report an unmet need for a medical examination.

Description

Progress in gender equality in the Netherlands since 2010

With 75.9 out of 100 points, the Netherlands ranks 3rd in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 7.9 points above the EU’s score. Since 2010, the Netherlands’ score has increased by 1.9 points, but its ranking has remained the same. Since 2018, the Netherlands’ score has increased by 1.8 points, mainly driven by improvements in the domain of power. Its ranking improved by two places.

Best Performance

The Netherlands’ ranking is among the highest in the domain of work in which it scores 78.3 points and is ranked 3rd among all Member States. The country ranks 1st in the sub-domain of gender segregation and quality of work, with a score of 73.9 points.

Most room for improvement

The Netherland’s score could be improved in the domain of knowledge (67.4 points) in which the country ranks 7th. Gender inequalities are most pronounced in the sub-domain of gender segregation in education. With a score of 53.1 points, the Netherlands ranks 13th among all Member States in this sub-domain.

Biggest improvement

Since 2018, the Netherlands’ score in the domain of power has improved by 6.8 points. Its ranking has improved by two places, from the 8th to the 6th place among all Member States. These changes were largely powered by an increase in gender equality in economic decision-making (+ 12.8 points) which has driven the score from 45.9 points in 2018 to 58.7 points in 2019.

A step backwards

Since 2010, the Netherlands’ score has decreased in the domain of time (– 2.0 points). Consequently, its ranking has dropped from the 1st to the 2nd place. This drop is driven by higher levels of gender inequality in social activities (– 7.7 points). In this sub-domain, the country’s ranking has also dropped from the 1st to the 2nd place.

Description

Progress in gender equality

With 77.3 out of 100 points, the Netherlands ranks 3rd in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 8.7 points above the EU’s score.

Since 2010, the Netherlands’ score has increased by 3.3 points, but its ranking has remained the same. Since 2019, the country’s score has improved by 1.4 points. Improvements in the domains of power and health have powered this change.

Best performance

The Netherlands’ ranking is the highest (2nd among all Member States) in the domain of time, in which it scores 83.9 points. In this domain, the country performs best in the sub-domain of social activities, ranking 2nd with a score of 88.7 points. Despite this strong performance, the Netherlands’ score in this sub-domain has decreased by 7.7 points since 2010.

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities are strongly pronounced in the domain of knowledge (67.0 points), in which the Netherlands ranks 7th. The country’s most room for improvement is in the sub-domain of segregation in education, scoring 51.7 points and ranking 15th. Since 2019, the Netherlands’ score in the domain of knowledge has fallen slightly by 0.4 points. This change is driven by growing levels of gender inequality in the sub-domain of gender segregation, in which the Netherlands’ score has decreased by 1.4 points, dropping two places.

Biggest improvement

Since 2019, the Netherlands’ score has improved the most in the domain of power (+ 4.9 points), ranking 6th among all Member States. This change is due to improvements in the sub-domains of economic (+ 10.9 points), social (+ 2.2 points) and political (+ 1.4 points) decision-making. In the sub-domain of economic decision-making, the country moved up four places (from the 7th to the 3rd place).

A step backwards

Since 2019, the Netherlands’ score has decreased slightly in the domain of money (– 0.4 points), ranking 7th. This change can be attributed to increasing gender inequality in the sub-domain of economic situation (– 1.4 points), resulting in a drop in the country’s ranking from the 6th to the 11th place.

Between 2010 and 2020, the Netherlands’ ranking has also dropped the most in the domain of money (from the 2nd to the 7th place). This is due to higher levels of gender inequality in the sub-domain of economic situation (– 4.4 points), consequently losing eight places. During this period, the country’s score in the domain of money has remained the same, with a score of 86.6 points.

Key highlights

Focus 2022: COVID-19 in the Netherlands

-

Women took on most of childcare duties and household tasks

In 2021, 43 % of women and 27 % of men reported caring for and supervising children aged 0–11 completely or mostly by themselves. During the pandemic, 30 % of women compared to 21 % of men spent more than four hours a day caring for their children or grandchildren aged 0–11. In addition, many more women (66 %) than men (21 %) reported assuming household chores completely or mostly by themselves. In 2021, 24 % of women compared to 19 % of men spent more than four hours a day doing housework.

-

Fewer women than men reduced or changed their working hours to provide care

In 2021, fewer women (6 %) than men (11 %) chose to reduce their working time to care for their children and/or relatives. Similarly, during the pandemic, 16 % of women compared to 26 % of men decided to change their working time to care for their children and/or other relatives. This is the highest proportion of men changing their working hours to perform care duties in the EU.

-

Slightly fewer women than men provided informal long-term care

In 2021, women (27 %) were slightly less likely than men (33 %) to provide informal long-term care for older people or people with health limitations. During the pandemic, 18 % of women and 19 % of men spent more than four hours a day providing informal long-term care. Nevertheless, fewer women (79 %) than men (82 %) with long-term care responsibilities participated in individual and social activities three times a week or more.

Description

Vooruitgang in gendergelijkheid in Nederland sinds 2010

Met 75,9 van de 100 punten neemt Nederland in de EU op de gendergelijkheidsindex de derde plaats in. De score is 7,9 punten hoger dan de score van de EU.

Sinds 2010 is de score van Nederland met 1,9 punten verbeterd, maar is het land op dezelfde plaats op de ranglijst blijven staan. Sinds 2018 is de score van Nederland met 1,8 punten verbeterd, met name vanwege verbeteringen in het domein macht. Het land is twee plaatsen gestegen op de ranglijst.

Beste prestatie

De positie van Nederland op de ranglijst behoort tot de hoogste in het domein werk, waarin het land 78,3 punten scoort en van alle lidstaten de derde plaats inneemt. In het subdomein gendersegregatie en kwaliteit van de arbeid neemt het land de eerste plaats in, met een score van 73,9 punten.

Meeste ruimte voor verbetering

De score van Nederland kan beter in het domein kennis (67,4 punten), waar het land op de zevende plek staat. Genderongelijkheden zijn het duidelijkst aanwezig in het subdomein gendersegregatie in het onderwijs. Met een score van 53,1 punten staat Nederland in dit subdomein dertiende van alle lidstaten.

Grootste verbetering

Sinds 2018 is de score van Nederland in het domein macht met 6,8 punten verbeterd. Het land is twee plaatsen gestegen, van de achtste naar de zesde plaats van alle lidstaten. Deze veranderingen waren grotendeels het gevolg van verbeterde gendergelijkheid in economische besluitvorming (+ 12,8 punten), die de score heeft verhoogd van 45,9 punten in 2018 naar 58,7 punten in 2019.

Een stap terug

Sinds 2010 is de score van Nederland in het domein tijd gedaald (– 2,0 punten). Het land is hierdoor gedaald van de eerste naar de tweede plaats. Deze daling is het gevolg van een grotere genderkloof op het gebied van sociale activiteiten (– 7,7 punten). In dit subdomein is het land ook gedaald van de eerste naar de tweede plaats.

Description

Vooruitgang op het gebied van gendergelijkheid

Met 77,3 van de 100 punten neemt Nederland in de EU op de gendergelijkheidsindex de derde plaats in. De score is 8,7 punten hoger dan de score voor de hele EU.

Sinds 2010 is de score van Nederland met 3,3 punten verbeterd, al is het land op dezelfde plaats op de ranglijst blijven staan. Sinds 2019 is de score van Nederland met 1,4 punt gestegen. Deze verandering vloeien voort uit verbeteringen in de domeinen macht en gezondheid.

Beste prestatie

Nederland scoort het hoogst in het domein tijd, met 83,9 punten, en neemt daar de tweede plaats in van alle lidstaten. In dit domein presteert het land het best in het subdomein sociale activiteiten, waar het met 88,7 punten op de tweede plaats staat. Ondanks deze sterke prestatie is de score van Nederland voor dit subdomein sinds 2010 met 7,7 punten gedaald.

Meeste ruimte voor verbetering

De genderkloof komt het sterkst tot uitdrukking in het domein kennis (67,0 punten), waar Nederland de zevende plaats inneemt. De meeste ruimte voor verbetering is er in het subdomein onderwijssegregatie, met een score van 51,7 punten (vijftiende plaats). Sinds 2019 is de score van Nederland in het domein kennis licht gedaald, met 0,4 punt. Deze daling wordt veroorzaakt door de toenemende genderkloof in het subdomein gendersegregatie (- 1,4 punt, waardoor Nederland twee plaatsen daalt op de ranglijst).

Grootste verbetering

Sinds 2019 is de score van Nederland het meest verbeterd in het domein macht (+ 4,9 punten), waarmee het land de zesde plaats op de ranglijst van alle lidstaten inneemt. Deze verandering houdt verband met verbeteringen in de subdomeinen economische, sociale en politieke besluitvorming (respectievelijk + 10,9, + 2,2 en + 1,4 punt). In het subdomein economische besluitvorming is het land vier plaatsen gestegen (van de zevende naar de derde plaats).

Een stap terug

Sinds 2019 is de score van Nederland in het domein geld licht gedaald, met 0,4 punt (zevende plaats). Deze verandering is toe te schrijven aan de toenemende genderkloof in het subdomein economische situatie (- 1,4 punt), waardoor het land van de zesde plaats is afgezakt naar de elfde.

Tussen 2010 en 2020 is Nederland ook stevig gedaald in het domein geld (van de tweede naar de zevende plaats). Dit is het gevolg van de toegenomen genderkloof in het subdomein economische situatie (- 4,4 punten), waardoor het land acht plaatsen is gezakt. In deze periode is de score van het land in het domein geld gelijk gebleven, bij een score van 86,6 punten.

Key highlights

Belangrijkste hoogtepunten

-

Vrouwen nemen het grootste deel van de zorg voor kinderen en het huishouden voor hun rekening

In 2021 nam 43 % van de vrouwen en 27 % van de mannen de zorg voor en het toezicht op kinderen van 0-11 jaar geheel of grotendeels zelf op zich. Tijdens de pandemie besteedde 30 % van de vrouwen, tegen 21 % van de mannen, meer dan vier uur per dag aan de zorg voor hun kinderen en kleinkinderen van 0-11 jaar. Bovendien verrichtten veel meer vrouwen (66 %) dan mannen (21 %) de huishoudelijke taken volledig of grotendeels zelf. In 2021 besteedde 24 % van de vrouwen, tegen 19 % van de mannen, meer dan vier uur per dag aan huishoudelijke taken.

-

Minder vrouwen dan mannen gingen minder werken of veranderden hun werktijden om zorg te verlenen

In 2021 zijn minder vrouwen (6 %) dan mannen (11 %) minder gaan werken om te zorgen voor hun kinderen en/of familieleden. Tijdens de pandemie besloot 16 % van de vrouwen en 26 % van de mannen hun werktijden aan te passen om te zorgen voor hun kinderen en/of andere familieleden. Dit is het hoogste percentage mannen in de EU die hun werktijden veranderen om zorgtaken te verrichten.

-

Vrouwen verleenden iets minder vaak dan mannen langdurige mantelzorg

In 2021 verleenden vrouwen (27 %) iets minder vaak dan mannen (33 %) langdurige mantelzorg aan ouderen of mensen met gezondheidsbeperkingen. Tijdens de pandemie besteedde 18 % van de vrouwen en 19 % van de mannen meer dan vier uur per dag aan de verlening van langdurige mantelzorg. Niettemin nam een kleiner percentage van de vrouwen met langdurige zorgtaken (79 %) minstens driemaal per week deel aan individuele en sociale activiteiten dan mannen in die categorie (82 %).

Description

Progress in gender equality

With 77.9 points out of 100, the Netherlands ranks 2nd in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 7.7 points above the score for the EU as a whole.1

Since 2010, the score for the Netherlands has increased by 3.9 points, mainly due to improvements in the domain of power (+ 15.8 points). Since 2020, the country’s score has increased slightly (+ 0.6 points). As a result, since 2020 the Netherlands has risen from 3rd to 2nd place in this domain. The country has seen the highest improvement in the domains of both power (+ 3.8 points) and knowledge (+ 2.1 points).

Best performance

The Netherlands ranks 1st in the EU for the domain of time, with a score of 76.9 points. Since 2020, the country has moved up one place despite a decrease of 7.0 points in this domain. This rise is mainly due to the differing paces of change in this domain in several countries. The Netherlands’ best ranking in the domain of time is in the sub-domain of social activities, in which it has risen from 2nd place in 2020 to currently rank 1st, with a score of 69.7 points. Within the domain of time, the Netherlands’ highest-scoring sub-domain is that of care activities (85.0 points), which has increased by 5.7 points since 2020, and in which it ranks 6th.

Most room for improvement

The Netherlands has the greatest room for improvement in the domain of knowledge (69.1 points). Despite gaining 2.1 points since 2020, faster progress on the part of other Member States has resulted in the Netherlands falling from 7th position to 8th in this domain. Within the domain of knowledge, the Netherlands ranks 16th in the sub-domain of segregation (52.0 points), falling one place since 2020.

Biggest improvement

Since 2020, the biggest rise in the Netherlands’ ranking has been in the domain of money, in which it has risen from 7th place to 5th. The country scores 88.1 points in this domain – an increase of 1.5 points since 2020, which was the third biggest increase among all EU countries in this domain. An improvement in the sub-domain of economic situation (+ 1.9 points) has been the key driver of this change. The Netherlands’ ranking has risen by four places to 7th in this sub-domain.

A step backwards

Since 2020, the Netherlands has fallen from 3rd to 5th place in the domain of work, despite a slight increase in score of 0.6 points. This backwards step in the ranking for this domain is due to a decrease in the sub-domain of segregation and quality of work (– 2.4 points), which resulted in the Netherlands dropping from 1st place to 5th in this sub-domain.

Convergence

Upward convergence in gender equality describes increasing equality between women and men in the EU, accompanied by a decline in variations between Member States. This means that countries with lower levels of gender equality are catching up with those with the highest levels, thereby reducing disparities across the EU. Analysis of convergence patterns in the Gender Equality Index shows that disparities between Member States decreased over the period 2010–2021, and that EU countries continue their trend of upward convergence.

Looking more closely at the performance of each Member State, patterns can be identified that reflect a relative improvement or slipping back in the Gender Equality Index score of each Member State in relation to the EU average.

The Netherlands is flattening. Its Gender Equality Index score is higher than the EU average, but has grown at a slower pace over time. The gap between the country and the EU average has narrowed over time.

Key highlights

Focus 2023: The European Green Deal

-

Women and men in the Netherlands are less likely to choose environmentally options than their counterparts elsewhere in the EU

In 2022, 36 % of women and 41 % of men in the Netherlands reported regularly choosing environmentally friendly options in childcare; for example, by avoiding single-use items, buying second-hand goods and educating the children under their care about environmental issues. In comparison, the EU average was 51 % for women and 49 % for men. Similarly, 47 % of both women and men regularly opted for environmentally friendly options in housework activities, such as recycling. These figures were lower than the EU average (59 % and 53 %, respectively).

-

Non-EU migrants in the Netherlands are experiencing energy-related difficulties

In the Netherlands, 7 % of non-EU migrant women and 10 % of non-EU migrant men reported being unable to keep their home adequately warm in 2021. Lone mothers (7 %) and lone fathers (2 %) also faced this challenge. Meanwhile, 4 % of both non-EU migrant women and men were in arrears on their utility bills in 2021, which was lower than the EU average (11 % and 12 %, respectively).

-

The Netherlands has a lower share of women than men working in its energy and transport sectors

In 2022, women made up just 21 % of workers in the energy sector in the Netherlands, which was 3 % lower than the EU average. In the same year, women represented 23 % of those employed in the transport sector in the Netherlands (just above the EU average of 22 %).

Description

Vooruitgang op het gebied van gendergelijkheid

Met 77,9 van de 100 punten neemt Nederland in de EU op de gendergelijkheidsindex de tweede plaats in. Daarmee scoort Nederland 7,7 punten hoger dan de EU als geheel.1

Sinds 2010 is de score voor Nederland met 3,9 punten gestegen, voornamelijk als gevolg van verbeteringen in het domein macht (+ 15,8 punten). Sinds 2020 is de score van het land licht omhoog gegaan (+ 0,6 punten). Daardoor is Nederland op dit domein sinds 2020 opgeklommen van de derde naar de tweede plaats. Het land heeft de grootste vooruitgang laten zien op de domeinen macht (+ 3,8 punten) en kennis (+ 2,1 punten).

Beste prestatie

Nederland neemt in de EU de eerste positie in op het domein tijd, met een score van 76,9 punten. Sinds 2020 is het land één plaats gestegen, ondanks een daling met 7,0 punten op dit domein. Deze stijging valt voornamelijk te verklaren door het verschillende tempo van de veranderingen op dit domein in bepaalde landen. Binnen het domein tijd behaalt Nederland de hoogste ranking op het subdomein sociale activiteiten, waar het met een score van 69,7 punten is gestegen van de tweede plaats in 2020 naar de eerste plaats nu. Binnen het domein tijd scoort Nederland het hoogst op het subdomein zorgactiviteiten (85,0 punten), waar het sinds 2020 een stijging met 5,7 punten laat zien en thans de zesde plaats inneemt.

Meeste ruimte voor verbetering

In Nederland bestaat de meeste ruimte voor verbetering in het domein kennis (69,1 punten). Ondanks een toename met 2,1 punten sinds 2020 heeft de snellere vooruitgang in andere lidstaten ertoe geleid dat Nederland op dit gebied van de zevende naar de achtste plaats is gedaald. Binnen het kennisdomein neemt Nederland de 16e plaats in op het subdomein segregatie (52,0 punten), waarmee het één plaats is gezakt sinds 2020.

Grootste verbetering

Nederland maakt de grootste sprong op de ranglijst sinds 2020 op het domein geld, waar het is gestegen van de zevende naar de vijfde plaats. Het land scoort hier 88,1 punten – een stijging met 1,5 punten sinds 2020, de op twee na grootste stijging van alle EU-lidstaten op dit domein. Een verbetering in het subdomein economische situatie (+ 1,9 punten) was de belangrijkste oorzaak van deze verandering. Op dit subdomein is Nederland vier plaatsen gestegen naar de zevende plek.

Een stap terug

Sinds 2020 is Nederland gezakt van de derde naar de vijfde plaats op het domein werk, ondanks een lichte stijging van de score met 0,6 punt. Deze stap terug op dit domein is toe te schrijven aan een daling van de score op het subdomein segregatie en arbeidskwaliteit (- 2.4 punten), waar Nederland is gezakt van de eerste naar de vijfde plaats.

Convergentie

Onder opwaartse convergentie op het gebied van gendergelijkheid wordt verstaan een toenemende gelijkheid tussen vrouwen en mannen in de EU, bij een gelijktijdige afname van de verschillen tussen de lidstaten. Dit betekent dat landen met een lager niveau van gendergelijkheid een inhaalslag maken ten opzichte van de landen met de hoogste niveaus, waardoor de verschillen in de EU kleiner worden. Uit een analyse van de convergentiepatronen in de gendergelijkheidsindex blijkt dat de verschillen tussen de lidstaten in de periode 2010-2021 zijn geslonken en dat de trend van opwaartse convergentie tussen de EU-landen doorzet.

Wanneer we de prestaties van de afzonderlijke lidstaten nader bestuderen, worden patronen zichtbaar die een relatieve verbetering of achteruitgang in de score van de gendergelijkheidsindex van elke lidstaat ten opzichte van het EU-gemiddelde laten zien.

De curve van Nederland vlakt af. De score van het land op de gendergelijkheidsindex ligt boven het EU-gemiddelde, maar is in de loop der tijd langzamer gestegen. Het verschil tussen Nederland en het EU-gemiddelde is in de loop der tijd kleiner geworden.

Key highlights

Uitgelichte resultaten

-

Vrouwen en mannen in Nederland kiezen minder vaak voor milieuvriendelijke opties dan burgers in andere lidstaten

In 2022 gaf 36 % van de vrouwen en 41 % van de mannen in Nederland aan regelmatig voor milieuvriendelijke opties te kiezen bij de verzorging van kinderen, bijvoorbeeld door wegwerpartikelen te vermijden, tweedehands spullen te kopen en milieubewustzijn te bevorderen bij hun kinderen. Ter vergelijking: het EU-gemiddelde was 51 % voor vrouwen en 49 % voor mannen. Daarnaast koos 47 % van zowel de vrouwen als mannen regelmatig voor milieuvriendelijke opties bij huishoudelijke activiteiten, zoals recycling. Deze cijfers lagen onder het EU-gemiddelde (respectievelijk 59 % en 53 %).

-

Niet-EU-migranten in Nederland ondervinden energiegerelateerde problemen

In Nederland meldde 7 % van de vrouwelijke en 10 % van de mannelijke migranten van buiten de EU dat ze hun huis in 2021 niet voldoende konden verwarmen. Ook alleenstaande moeders (7 %) en vaders (2 %) zagen zich geconfronteerd met dit probleem. Tegelijkertijd had 4 % van de vrouwelijke en mannelijke migranten van buiten de EU in 2021 een betalingsachterstand bij rekeningen voor nutsvoorzieningen, een cijfer dat onder het EU-gemiddelde ligt (respectievelijk 11 % en 12 %).

-

In Nederland werken minder vrouwen dan mannen in de energie- en de vervoerssector

In 2022 was slechts 21 % van de werknemers in de energiesector in Nederland vrouw, 3 % minder dan het EU-gemiddelde. In hetzelfde jaar maakten vrouwen 23 % van de werknemers uit in de Nederlandse vervoerssector(dit aandeel ligt net boven het EU-gemiddelde van 22 %).

Domain information

Description

In the domain of work, greater participation of women and men in employment and decreasing gender gaps have contributed to an increase in the score.

The employment rate (20-64) is 71 % for women versus 82 % for men. The total employment rate is 76.4 %, indicating that the Netherlands has nearly reached its national Europe 2020 (EU2020) strategy target (80 %).

For both women and men, the employment rate decreases and the gender gap widens when the number of hours worked is taken into account. The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate of women is approximately 35 %, compared to 57 % for men.

Among couples with children, the FTE employment rate for women is 44 %, compared to 79 % for men. The gender gap (35 percentage points (p.p.)) is much higher compared to that of couples without children (14 p.p.).

The FTE employment rate increases and the gender gap shrinks as education levels rise.

Over three quarters (77 %) of women work part-time, compared to 28 % of men. On average, women work 25 hours per week, compared to 35 hours per week for men. 20 % of working-age women versus 1.4 % of working-age men are either outside the labour market or work part-time due to care responsibilities.

Gender segregation in the labour market is a reality for both women and men. Nearly 37 % of women work in education, human health and social work activities (EHW), compared to 10 % of men. More than nine times more men (28 %) than women (3 %) work in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations.

Description

The situation in the domain of money has improved. Gender equality improved in earnings and income as well as in the poverty rate and distribution of wealth from 2005 to 2015.

Mean monthly earnings of women and men have increased, but women continue to earn about 21 % less than men. The gap is bigger among couples with children, where women earn 48 % less than men.

The population at risk of poverty has increased slightly for both women and men. 28 % of lone mothers are at risk of poverty, compared to 4 % of lone fathers. The risk of poverty is slightly lower for women and men who have obtained a high level of education than for those with low and middle levels of education.

Inequalities in income distribution have remained unchanged amongst women and have decreased amongst men. As such, the gender gap has decreased. Regardless, men earn more than women, and the gender pay gap is 16 % – the same gap as the EU-28 average. In 2012, the gender gap in pensions was 42 % to the detriment of women, which is higher than the EU-28 average of 38 %.

Description

In the domain of knowledge, the score increased primarily due to improved educational attainment and participation among women and men.

The number of tertiary graduates has increased, especially for women. However, there are still slightly more men (29 %) than women (27 %) with a tertiary degree. With 46 % of people aged 30-34 having obtained tertiary education, the Netherlands has met its Europe 2020 strategy target (40 %).

The rate of participation in lifelong learning has slightly increased for both women and men.

Only 20 % of women with disabilities have attained tertiary education, compared to 36 % of women without disabilities. 28 % of men with disabilities have attained tertiary education, compared to 40 % of men without disabilities.

Gender segregation in study fields remains a major challenge. The gender gap in tertiary education in education, health and welfare, humanities and arts has decreased, but levels remain relatively high. 40 % of women students are concentrated in these fields, which are traditionally seen as ‘feminine’, compared to 21 % of men. In 2005, 53 % of women students were concentrated in these fields.

Description

In the domain of time, the score has decreased. The greatest challenge remains the uneven division of time for social activities between women and men.

Although gender gaps have decreased, women continue to do the bulk of caring tasks within the family. 81 % of women do cooking and housework every day for at least 1 hour, compared to 47 % of men.

Among couples without children, women do cooking and housework more than men (86 % versus 39 %). This gender gap is bigger than in couples with children, where 92 % of women do the cooking, compared to 55 % of men.

71 % of women aged 25-49 care for and educate their family members for at least 1 hour per day, compared to 50 % of men in the same age group.

93 % of women in a couple with children care for and educate their family every day for 1 hour or more, compared to 83 % of men.

Inequality in time-sharing at home also extends to social activities. Men are slightly more likely than women to participate in sporting, cultural, and leisure activities outside the home.

The Netherlands has met both ‘Barcelona targets’ of enrolling 33 % of children under the age of three in childcare (46 %), and 90 % of children between the age of three and school age (91 %).

Description

The domain of power shows a marked increase, due to a considerable improvement in the sub-domain of economic power. Nevertheless, this remains the lowest score of all the domains for the Netherlands.

From 2005 to 2015, the representation of women on the corporate boards of publicly listed companies more than tripled (from 7 % in 2005 to 26 % in 2015). Women’s representation on the board of the central bank has remained quite stable: they held 7 % of board seats in 2005 and 8 % of board seats in 2015.

The slight increase in the sub-domain of political power is due to the increased gender balance in parliament, from 36 % to 37 % women, as well as the increased gender balance in women ministers, from 36 % to 38 %.

With regards to the sub-domain of social power, which has regressed, approximately one third of board members of research funding organisations are women. 38 % of board members of publicly owned broadcasting organisations are women. The gender gap in decision-making in sport is higher, however — women comprise just 26 % of members of the highest decision-making bodies of national Olympic sport organisations.

Description

In the domain of health, the score has remained stable due to improved and relatively equal access to medical and dental services, coupled with a declining health status.

Unmet medical and dental needs have decreased, and almost all women and men are able to meet these needs. Less than 1 % of women and men have unmet needs for medical examination or for dental examination.

Life expectancy has slightly increased for both women and men. Women on average live 3 years longer than men.

The number of healthy life years, however, decreased for both women and men (by 6 years and 4 years, respectively) from 2005 to 2015.

73 % of women and 80 % of men rate their health as ‘good’ or ‘very good’.

Compared to lone fathers, lone mothers are more satisfied with their health (62 % and 75 %, respectively).

More men smoke and/or are involved in harmful drinking than women (42 % versus 28 %). More men than women (41 % versus 37 %), however, engage in healthy behaviour (physical activities and/or consuming fruit and vegetables).

Description

Violence against women is included in the Gender Equality Index as a satellite domain. This means that the scores of the domain of violence do not have an impact on the final score of the Gender Equality Index. From a statistical perspective, the domain of violence does not measure gaps between women and men as core domains do. Rather, it measures and analyses women’s experiences of violence. Unlike other domains, the overall objective is not to reduce the gaps of violence between women and men, but to eradicate violence completely.

A high score in the Gender Equality Index means a country is close to achieving a gender-equal society. However, in the domain of violence, the higher the score, the more serious the phenomenon of violence against women in the country is. On a scale of 1 to 100, 1 represents a situation where violence is non-existent and 100 represents a situation where violence against women is extremely common, highly severe and not disclosed. The best-performing country is therefore the one with the lowest score.

The Netherlands’ score for the composite measure of violence is 31.5, which is higher than the EU-28 average.

In the Netherlands, 45 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once since the age of 15. This is higher than the EU-28 average of 33 %.

13 % of women who have experienced physical or sexual violence by any perpetrator in the past 12 months have not told anyone. This rate is roughly the same as the EU-28 average.

At the societal level, violence against women costs the Netherlands an estimated EUR 7.5 billion per year through lost economic output, service utilisation and personal costs (1).

The domain of violence is made up of three sub-domains: prevalence, which measures how often violence against women occurs; severity, which measures the health consequences of violence and disclosure; which measures the reporting of violence.

[1] This is an exercise done at EU level to estimate the costs of the three major dimensions: services, lost economic output and pain and suffering of the victims. The estimates were extrapolated to the EU from a United Kingdom case study, based on population size. EIGE, Estimating the costs of gender-based violence in the European Union, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2014, p 142.

Description

The Netherlands’ score in the domain of work is 77.4, showing progress of 2.6 points since 2005 (+ 0.7 points since 2015), with improvements in the sub-domain of participation. The Netherlands continues to rank third in the EU in the domain of work since 2005.

The employment rate (of people aged 20-64) is 74 % for women and 84 % for men. With the overall employment rate of 79 %, the Netherlands is not far from reaching its national EU 2020 employment target of 80 %. The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate increased from 35 % to 37 % for women and decreased from 62 % to 58 % for men between 2005 and 2017, narrowing the gender gap (from 28 percentage points (p.p.) to 21 p.p.). Between women and men in couples with children, the gap is much wider than in couples without children (31 p.p. and 14 p.p.). Around 76 % of women work part-time, compared to 29 % of men. On average, women work 25 hours per week and men 35.

The uneven concentration of women and men in different sectors of the labour market remains an issue: 35 % of women work in education, health and social work, compared to 10 % of men. Fewer women (4 %) than men (28 %) work in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations.

Description

The Netherlands’ score in the domain of money is 86.7, showing progress of 4.5 points since 2005 (- 0.1 points since 2015), with improvements in the financial situations of women and men. The Netherlands ranks sixth in the EU in the domain of money and is 6.2 points above the EU’s score.

Although mean monthly earnings increased for both women (+ 14 %) and men (+ 8 %) from 2006 to 2014, the gender gap persists: women earn 21 % less than men. In couples with children, women earn 46 % less than men (36 % less for women in couples without children).

The risk of poverty increased between 2005 and 2017: 13 % of both women (+ 4 p.p.) and men (+ 4 p.p.) are at risk. People facing the highest risk of poverty are lone parents (32 %), single men (26 %), young people aged 15-24 (25 %) and men born outside the Netherlands (25 %). Inequalities in income distribution increased among women and slightly decreased among men as well as between women and men from 2005 to 2017. Women earn on average 85 cents for every euro a man makes per hour, resulting in a gender pay gap of 15 %. The gender pension gap is 41 %.

Description

The Netherlands’ score in the domain of knowledge is 67.1, a 3.2-point increase from 2005 (- 0.2 points since 2015). The Netherlands ranks seventh in the domain of knowledge in the EU, 3.6 points above the EU’s score. Attainment and participation have improved significantly. The Netherlands ranks second in the EU in this sub-domain.

The share of women tertiary graduates continues to be lower than the share of men, although the gender gap has narrowed between 2005 and 2017 (from 5 p.p. to 2 p.p.). Around 29 % of women and 31 % of men have tertiary degrees (compared to 22 % and 27 % in 2005). The gender gap is wider between women and men aged 65 or more (15 p.p.), with more men tertiary graduates. The Netherlands has met its national EU 2020 target of having at least 40 % of people aged 30-34 with tertiary education. The current rate is 49 % (with 53 % for women and 46 % for men). Participation in lifelong learning somewhat increased between 2005 and 2017. About 26 % of women and 25 % of men engage in formal and non-formal education and training. The Netherlands has the fifth highest participation rate in the EU.

The uneven concentration of women and men in different study fields in tertiary education continues to be a challenge for the Netherlands. Around 38 % of women students study education, health and welfare, or humanities and arts, compared to 20 % of men students.

Description

The Netherlands’ score in the domain of time has not changed since the last edition of the Index, because new data is not available. The next data update for this domain is expected in 2021. More frequent time-use data would help to track progress in this domain.

In the domain of time, the Netherlands’ score is 83.9, which is the second highest score in the EU. Gender inequalities in time-share for care responsibilities remain an issue, while participation of both women and men in social activities has decreased since 2005. Women take on more care responsibilities in the family: 39 % of women care for and educate their family members for at least one hour per day, compared to 28 % of men. The gender gap has decreased (from 14 p.p. to 10 p.p.) since 2003. In couples with children, 93 % of women and 83 % of men take care of their family daily. More women (81 %) than men (47 %) do cooking and housework every day for at least one hour.

A lower share of women (56 %) than men (58 %) participates in sporting, cultural and leisure activities outside the home. Around 22 % of both women and men are involved in voluntary or charitable activities.

Description

The Netherlands’ score in the domain of power is 50.0, with a 9.7-point increase since 2005 (- 2.9 points since 2015). It is the lowest score for the Netherlands across all domains, 1.9 points below the EU’s score in this domain. Since 2005, the sub-domain of economic power has improved, while there has been a regression in the sub-domain of social power. The Netherlands ranks 12th in the domain of power in the EU.

The share of women increased among ministers (from 35 % to 42 %) between 2005 and 2018 and the share of women among members of regional assemblies rose from 28 % to 32 %. The share of women parliamentarians slightly decreased over the same time period (from 36 % to 35 %).

The sub-domain of economic power improved between 2005 and 2018, due to increased shares of women on the boards of the largest publicly listed companies (from 7 % to 30 %). In contrast, the share of women on the board of the central bank dropped from 11 % to 0 % over the same time period. In the sub-domain of social power, women comprise one third of board members of both research-funding organisations and publicly owned broadcasting organisations and 26 % of board members of the highest decision-making bodies of national Olympic sports organisations.

Description

The Netherlands’ score in the domain of health is 90.0, with no significant change since 2005 (+ 0.1 points since 2015). There are small improvements in access to health services, while health status has slightly worsened (with no new data for the sub-domain of health behaviour).

Self-perceptions of good health did not change from 2005 to 2017. Around 73 % of women and 79 % of men consider themselves to be in good health. Health satisfaction increases with a person’s level of education and decreases in proportion to their age. Life expectancy increased for both women and men between 2005 and 2016. Women on average live three years longer than men (83 years compared to 80 years). The number of healthy life years decreased in the Netherlands, from 64 to 58 for women and from 65 to 63 for men.

The Netherlands has the highest score in the sub-domain of access to health services in the EU. Less than 1 % of both women and men report unmet medical needs (compared to 2 % and 1 % in 2005). Almost no women and men report unmet needs for dental examinations (less than 1 % for both compared to 7 % of women and 8 % of men in 2005). Men born outside of the EU report the most unmet needs for medical care (12 %), 8 p.p. higher than women born outside of the EU and 10 p.p. higher than men born in the Netherlands.

Description

Why is there no score for the violence domain?

There is no new data to update the score for violence, which is why no figure is given. Eurostat is currently coordinating an EU-wide survey on gender-based violence, with results expected in 2023. EIGE will launch a second round of administrative data collection on intimate partner violence, rape and femicide in 2022. Both data sources will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024.

Unlike the other domains of the Index, the domain of violence does not measure differences between women’s and men’s situations; rather, it examines women’s experiences of violence (prevalence, severity and disclosure). The overall objective is not to reduce the gaps in violence between women and men, but to eradicate violence completely.

Data gaps mask the true scale of violence

The EU needs comprehensive, up-to-date and comparable data to develop effective policies that combat violence against women.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, women in violent relationships were stuck at home and exposed to their abuser for long periods of time, putting them at greater risk of domestic violence. Even without a pandemic, women face the greatest danger from people they know.

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on violence against women and domestic violence. The Netherlands signed the Istanbul Convention in November 2012 and ratified it in November 2015. The treaty entered into force in March 2016.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to the Netherlands in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on mobility and increased isolation exposed women to a higher risk of violence committed by an intimate partner. While the full extent of violence during the pandemic is difficult to assess, media and women’s organisations have reported a sharp increase in the demand for services for women victims of violence. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated pre-existing gaps in the prevention of violence against women and the provision of adequately funded victim support services.

Eurostat is currently coordinating a survey on gender-based violence in the EU but not all Member States are taking part. EIGE, together with the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), will collect data for the remaining countries to have an EU-wide comparable data on violence against women. Data collection will be completed in 2023, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024.

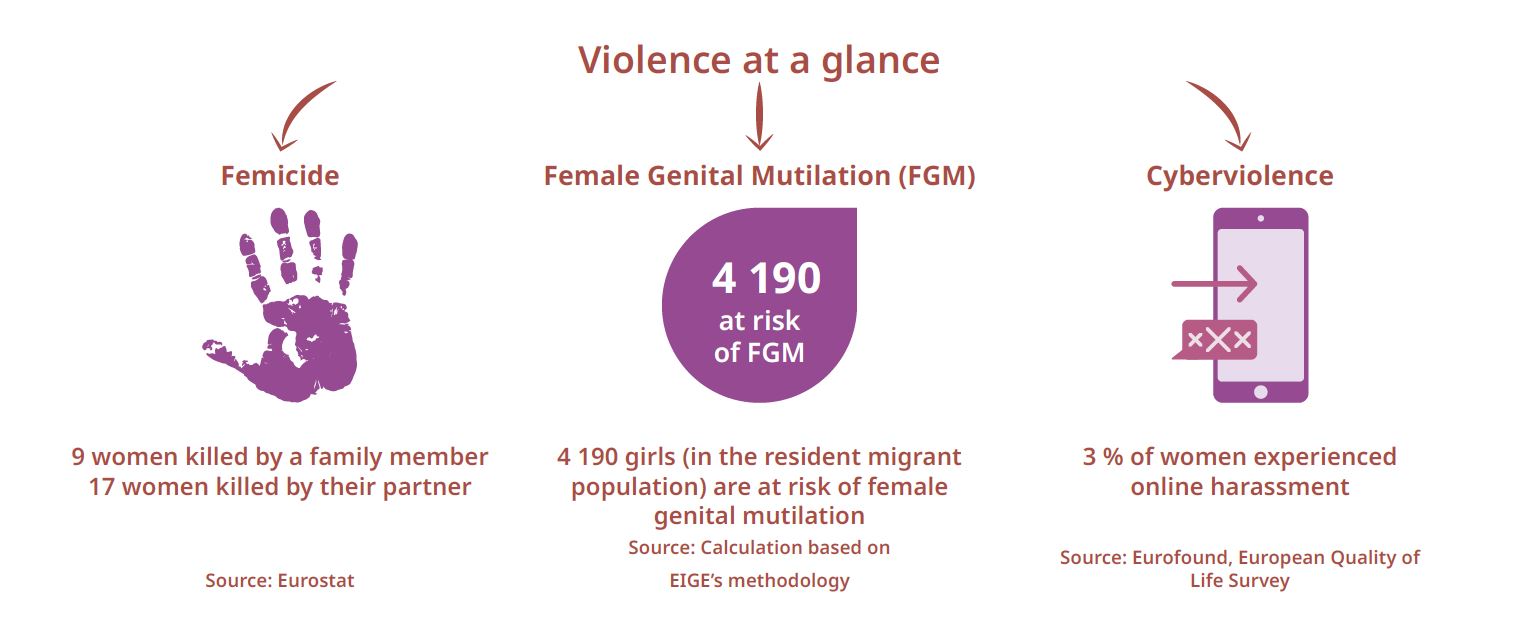

Violence at a glance

- Femicide

In 2018, over 600 women were murdered by an intimate partner, a family member, or a relative in 14 EU Member States, according to official reports. In the Netherlands, three women were killed by a family member and 28 women were killed by their partners in 2018.

Source: Eurostat, 2018 - Physical and/or sexual violence

40 % % of women who experienced physical and/or sexual violence, experienced it in their own home .

15 % of trans women, 8 % of lesbian women and 6 % of bisexual women were physically or sexually attacked in the past five years for being LGBTI.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey and LGBTI Survey II, 2019 - Harassment

59 % of women experienced harassment in the past five years, and 44 % in the past 12 months.

69 % of women with disabilities experienced harassment in the past five years, and 54 % in the past 12 months.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey, 2019 - Cyberviolence

18 % of women were subjected to cyber harassment in the past five years, and 11 % in the past 12 months.

Among women aged 16-29, 25 % experienced cyber harassment in the past five years, and 13 % in the past 12 months.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey, 2019 - Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

An estimated 4 190 girls in the resident migrant population were in 2017 are at risk of female genital mutilation in the next 20 years.

Source: Kawous et al. calculation, 2020

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. The Netherlands signed the Istanbul Convention in November 2012 and ratified it in November 2015. The treaty entered into force in March 2016.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to the Netherlands in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

Femicide

In 2020, 788 women were murdered by an intimate partner, a family member or a relative in 17 EU Member States, according to official reports. In the Netherlands, 15 women were killed by a family member and 24 women were killed by their partners in 2020.

Source: Eurostat, 2020

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. The Netherlands signed the Istanbul Convention in November 2012 and ratified it in November 2015. The treaty entered into force in March 2016.

EIGE/FRA survey

The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) will carry out a survey on violence against women (VAW II) in eight EU Member States (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), which will complement the Eurostat-led data collection on gender-based violence and other forms of interpersonal violence (EU-GBV) in the remaining countries. The use of a unified methodology will ensure the availability of comparable data across all EU Member States. Data collection will be completed in 2023, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024 and its thematic focus on violence against women.

Description

Gebrek aan bewijsmateriaal om geweld tegen vrouwen te beoordelen

Nederland heeft geen score gekregen voor het domein geweld, vanwege een gebrek aan vergelijkbare EU-brede gegevens.

Tijdens de COVID-19-pandemie waren vrouwen door beperkingen van de mobiliteit en grotere isolatie blootgesteld aan een groter risico van geweld door hun partner. De volle omvang van het geweld tijdens de pandemie is lastig te beoordelen, maar media en vrouwenorganisaties hebben een sterke toename gemeld in de vraag naar diensten voor vrouwelijke slachtoffers van geweld. Tegelijkertijd heeft de COVID-19-pandemie bestaande kloven aan het licht gebracht en vergroot in de preventie van geweld tegen vrouwen en het aanbod van voldoende gefinancierde ondersteuningsdiensten voor slachtoffers.

Eurostat coördineert momenteel een enquête over gendergerelateerd geweld in de EU, maar niet alle lidstaten doen hieraan mee. EIGE verzamelt, samen met het Bureau van de Europese Unie voor de grondrechten (FRA), gegevens voor de overige landen, om zo te komen tot EU-brede vergelijkbare gegevens over geweld tegen vrouwen. De gegevensverzameling wordt in 2023 afgerond en de resultaten worden gebruikt om het domein geweld in de gendergelijkheidsindex 2024 te actualiseren.

Geweld in één oogopslag

- Femicide

In 2018 zijn volgens officiële verslagen meer dan 600 vrouwen vermoord door hun partner of een gezins- of familielid, in 14 EU-lidstaten. In Nederland zijn in 2018 drie vrouwen gedood door een familielid en 28 vrouwen door hun partner.

Bron: Eurostat, 2018 - Fysiek en/of seksueel geweld

Bij 40 % van de vrouwen die met fysiek en/of seksueel geweld te maken hebben gehad, was dit in hun eigen huis .

15 % van de transgender vrouwen, 8 % van de lesbische vrouwen en 6 % van de biseksuele vrouwen is in de afgelopen vijf jaar fysiek of seksueel aangevallen omdat ze LGBTI zijn.

Bron: Enquête over de grondrechten en LGBTI-enquête II van het FRA, 2019 - Intimidatie

59 % van de vrouwen heeft in de afgelopen vijf jaar met intimidatie te maken gehad, en 44 % in de afgelopen twaalf maanden.

69 % van de vrouwen met een handicap heeft in de afgelopen vijf jaar met intimidatie te maken gehad, en 54 % in de afgelopen twaalf maanden.

Bron: Enquête over de grondrechten van het FRA, 2019 - Cybergeweld

18 % van de vrouwen heeft in de afgelopen vijf jaar met cyberpesten te maken gehad, en 11 % in de afgelopen twaalf maanden.

Van de vrouwen van 16-29 jaar heeft 25 % in de afgelopen vijf jaar met cyberpesten te maken gehad, en 13 % in de afgelopen twaalf maanden.

Bron: Enquête over de grondrechten van het FRA, 2019 - Vrouwelijke genitale verminking (VGV)

Naar schatting liepen 4 190 meisjes in de populatie van verblijvende migranten in 2017 risico op vrouwelijke genitale verminking in de komende twintig jaar.

Bron: Berekening Kawous et al., 2020

Verdrag van Istanbul: stand van zaken

Het Verdrag van Istanbul is het meest omvattende internationale mensenrechtenverdrag inzake preventie en bestrijding van geweld tegen vrouwen en huiselijk geweld. Nederland heeft het Verdrag van Istanbul in november 2012 ondertekend en in november 2015 geratificeerd. Het verdrag is in maart 2016 in werking getreden.

Description

Gebrek aan gegevensmateriaal om geweld tegen vrouwen te beoordelen

Nederland heeft geen score gekregen voor het domein geweld, vanwege een gebrek aan vergelijkbare EU-brede gegevens.

Femicide

In 2020 zijn volgens officiële meldingen in 17 EU-lidstaten 788 vrouwen vermoord door hun partner of een gezins- of familielid. Er zijn in 2020 in Nederland 15 vrouwen gedood door een familielid en 24 vrouwen door hun partner.

Bron: Eurostat, 2020

Verdrag van Istanbul: stand van zaken

Het Verdrag van Istanbul is het meest omvattende internationale mensenrechtenverdrag inzake preventie en bestrijding van geweld tegen vrouwen en huiselijk geweld. Nederland heeft het Verdrag van Istanbul in november 2012 ondertekend en in november 2015 geratificeerd. Het verdrag is in maart 2016 in werking getreden.

Enquête van EIGE en FRA

Het Bureau van de Europese Unie voor de grondrechten (FRA) en het Europees Instituut voor gendergelijkheid (EIGE) zullen in acht EU-lidstaten (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE) een enquête houden over geweld tegen vrouwen (VAW II), in aanvulling op de door Eurostat geleide gegevensverzameling over gendergerelateerd geweld en andere vormen van interpersoonlijk geweld (EU-GBV) in de overige lidstaten. Door een uniforme methode te gebruiken zullen voor alle EU-lidstaten vergelijkbare gegevens beschikbaar zijn. De gegevensverzameling wordt in 2023 afgerond en de resultaten zullen worden gebruikt om het domein geweld in de gendergelijkheidsindex 2024 en de bijbehorende thematische focus “geweld tegen vrouwen” te actualiseren.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to the Netherlands in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

Femicide

In 2021, 720 women were murdered by an intimate partner, family member or relative in 17 EU Member States, according to official reports. In the Netherlands, 23 women were murdered by an intimate partner, and four women were murdered by a family member.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

Violence at a glance

-

Intimate partner violence

In the Netherlands, around 33 % of women who have ever been in a relationship have experienced violence by an intimate partner during their adult life. In total, 17 % have experienced physical violence (including threats) or sexual violence, while 32 % have experienced psychological violence. Up to 5 % have experienced intimate partner violence during the last 12 months, and 13 % have experienced it in the last five years.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

-

Sexual harassment at work

In the Netherlands, 41 % of all women who have ever worked have experienced sexual harassment at work. Around 7 % of women have experienced sexual harassment at work during the last 12 months, while up to 19 % have experienced it in the last 5 years.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. The Netherlands signed the Istanbul Convention in November 2012, and ratified it in November 2015. The Convention entered into force in the Netherlands in March 2016.

The European Council approved the EU’s accession to the Istanbul Convention on 1 June 2023.

EIGE/FRA survey on violence against women

The Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) will carry out a survey on violence against women (VAW II) in eight EU Member States (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), which will complement the Eurostat-led data collection on gender-based violence and other forms of interpersonal violence (EU-GBV) in the remaining countries. The use of a unified methodology will ensure the availability of comparable data across all EU Member States. Data collection will be completed this year, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024, with its thematic focus on violence against women.

Description

Gebrek aan gegevensmateriaal om geweld tegen vrouwen te beoordelen

Nederland heeft geen score gekregen voor het domein geweld, vanwege een gebrek aan vergelijkbare EU-brede gegevens.

Femicide

In 2021 zijn volgens officiële berichten in 17 van de 27 EU-lidstaten 788 vrouwen vermoord door een intieme partner of een gezins- of familielid. In Nederland werden 23 vrouwen vermoord door een intieme partner en vier vrouwen door een familielid.

Bron: Eurostat, 2021

Geweld in één oogopslag

-

Huiselijk geweld

In Nederland heeft ongeveer 33 % van de vrouwen die ooit een relatie hebben gehad, op volwassen leeftijd te maken gehad met geweld door een intieme partner. In totaal heeft 17 % fysiek geweld (waaronder bedreigingen) of seksueel geweld ondervonden, terwijl 32 % met psychologisch geweld werd geconfronteerd. Bijna 5 % heeft in de afgelopen twaalf maanden partnergeweld ervaren, 13 % in de afgelopen vijf jaar.

Bron: Eurostat, 2021

-

Seksuele intimidatie op het werk

In Nederland heeft 41 % van alle vrouwen die ooit hebben gewerkt, te maken gehad met seksuele intimidatie op het werk. Ongeveer 7 % van de vrouwen heeft in de afgelopen twaalf maanden seksuele intimidatie op het werk ervaren, voor bijna 19 % was dit in de afgelopen vijf jaar het geval.

Bron: Eurostat, 2021

Verdrag van Istanbul: stand van zaken

Het Verdrag van Istanbul is het meest omvattende internationale mensenrechtenverdrag inzake het voorkomen en bestrijden van geweld tegen vrouwen en huiselijk geweld. Nederland heeft het Verdrag van Istanbul in november 2012 ondertekend en in november 2015 geratificeerd. Het verdrag is in maart 2016 in Nederland in werking getreden.

De Europese Raad heeft op 1 juni 2023 zijn goedkeuring gehecht aan de toetreding van de EU tot het Verdrag van Istanbul.

Enquête van EIGE en FRA naar geweld tegen vrouwen

Het Bureau van de Europese Unie voor de grondrechten (FRA) en het Europees Instituut voor gendergelijkheid (EIGE) zullen in acht EU-lidstaten (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE) een enquête houden over geweld tegen vrouwen (VAW II), in aanvulling op de door Eurostat georganiseerde verzameling van gegevens over gendergerelateerd geweld en andere vormen van interpersoonlijk geweld (EU-GBV) in de overige lidstaten. Door een uniforme methode te gebruiken zullen voor alle EU-lidstaten vergelijkbare gegevens beschikbaar zijn. De gegevensverzameling wordt in 2023 afgerond en de resultaten zullen worden gebruikt om het domein geweld in de gendergelijkheidsindex 2024 en de bijbehorende thematische focus “geweld tegen vrouwen” te actualiseren.

Thematic focus information

Description

In 2016, 36 % of women and 25 % of men aged 20-49 (potential parents) were ineligible for parental leave in the Netherlands. Unemployment or inactivity was the main reason for ineligibility for 63 % of women and 48 % of men. The remaining 37 % of women and 52 % of men were ineligible for parental leave due to inadequate length of employment.

Same-sex couples are eligible for parental leave in the Netherlands. Among the employed population, 17 % of women and 15 % of men were ineligible for parental leave.

Description

Most informal carers for older persons and/or persons with disabilities in the Netherlands are women (60 %). The shares of women and men involved in informal care for older persons and/or people with disabilities several days a week or every day are 11 % and 8 %. The proportion of women involved in informal care is 4 p.p. lower than the EU average, while the involvement of men is 2 p.p. lower. About 17 % of women and 10 % of men aged 50-64 take care of older persons and/or persons with disabilities, in comparison to 10 % of women and 4 % of men in the 20-49 age group. Around 47 % of women carers for older persons and/or persons with disabilities are employed, compared to 54 % of men combining care with professional responsibilities.

There are also fewer women than men informal carers working in the EU. But the gender gap is narrower in the Netherlands than in the EU (7 p.p. compared to 14 p.p. for the EU). In the 50-64 age group, 49 % of women informal carers work, compared to 73 % of men. Around 43 % of women and men in the Netherlands report unmet needs for professional home care services.

Description

In the Netherlands, 57 % of all informal carers of children are women. Overall, 59 % of women and 52 % of men are involved in caring for or educating their children or grandchildren at least several times a week. Compared to the EU average (56 % of women and 50 % of men), more women and men are involved in caring for or educating their children or grandchildren in the Netherlands. The gender gaps are wider between women and men who are working (79 % and 64 %), within the 20-49 age group (97 % and 83 %), and between women and men working in the private sector (79 % and 62 %).

The Netherlands has reached both Barcelona targets to have at least 33 % of children below the age of three and 90 % of children between the age of three and school age in childcare. Around 62 % of children below the age of three are under some form of formal care arrangements (only 6 % of children this age are in formal childcare for at least 30 hours a week), which is the second highest coverage in the EU. Formal childcare is provided for 95 % of children from the age of three to the minimum compulsory school age (20 % are in formal childcare for at least 30 hours a week).

Around 13 % of households report unmet needs for formal childcare services in the Netherlands. Lone mothers are more likely to report higher unmet needs for formal childcare services (18 %), compared to couples with children (13 %).

Description

In the Netherlands, men spend slightly more time commuting to and from work than women (around 47 minutes per day for men and 43 minutes for women). Couples without children spend a greater amount of time commuting compared to couples with children, with men travelling around 6-7 minutes more than women in both cases. Single women commute around 45 minutes per day, compared to 43 minutes for single women. Women spend more time commuting than men, regardless of whether they work part-time or full-time. Women working part-time travel 41 minutes from home to work and back, and men commute 39 minutes, compared to 52 minutes for women and 50 minutes for men working full-time.

Generally, men are more likely to travel directly to and from work, whereas women make more multi-purpose trips, to fit in other activities such as school drop-offs or grocery shopping.

Description

Fewer women (33 %) than men (39 %) have no control over their working time arrangements. Access to flexible working arrangements is higher in the Netherlands than in the EU, where 57 % of women and 54 % of men have no possibility of changing their working time arrangements. Around one third of women in the private (33 %) and the public (35 %) sectors, and 41 % of men in both sectors, have no control over their working time arrangements.

Even though there are more women than men working parttime in the Netherlands, far fewer women (6 %) than men (23 %) part-time workers transitioned to full-time work in 2017. The gender gap is wider than in the EU, where 14 % of women and 28 % of men moved from part-time to full-time work.

Description

The Netherlands has the fourth highest participation rate in lifelong learning (19 %) in the EU, with a gender gap of 2 p.p. Women (aged 25-64) are more likely to participate in education and training than men regardless of their employment status, except for economically inactive men, who are more likely to participate in lifelong learning than economically inactive women (13 % compared to 11 %). Conflicts with work schedules are as great a barrier to participation in lifelong learning for women as for men (29 %). Family responsibilities are reported as a barrier to engagement in education and training for 44 % of women compared to 29 % of men.

Family responsibilities are more of an obstacle for participation in lifelong learning in the Netherlands than in the EU overall, while work schedules are reported as less of an obstacle than the EU average. In the EU, 38 % of women and 43 % of men report their work schedule as an obstacle, and 40 % of women and 24 % ofmen report that family responsibilities hinder participation in lifelong learning.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2020 focuses on digitalisation and the future of work. The thematic focus looks at three areas:

- use and development of digital skills and technologies

- digital transformation of the world of work

- broader consequences of digitalisation for human rights, violence against women and caring activities

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2021 focuses on gender inequalities in health. The thematic focus analyses the following aspects of health in the EU:

- health status and mental health

- heath behaviour

- access to health services

- sexual and reproductive health

- the COVID-19 pandemic.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2022 focuses on socio-economic consequences resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The thematic focus analyses the following aspects:

- Childcare

- Long-term care

- Housework

- Flexible working arrangement

The data was gathered using a survey that was carried out in all EU Member States between June and July 2021. Both the survey design and data collection timeframe ensured a comprehensive coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact. The survey was conducted using an international web panel with a quota sampling method based on a stratification approach[1]. It targeted the general population, aged between 20 and 64 years. Representative quotas were designed based on 2020 Eurostat population statistics. Post-stratification weighting was carried out to adjust for differences between the sample and population distribution in key variables and to ensure the sample accurately reflected the socio-demographic structure of the target population.

[1] The data was collected via a web survey using the international panel platform CINT as a main resource. CINT is an international platform that brings together several international panels, reaching more than 100 million registered panellists across more than 150 countries. To fulfil the required sampling in small countries, additional panel providers (IPSOS, TOLUNA, KANTAR) were engaged, which allowed for the same profiling requirements of the respondents and GDPR compliance.

Description

De gendergelijkheidsindex 2021 richt zich op genderongelijkheden op gezondheidsgebied. Binnen de thematische focus worden de volgende aspecten van gezondheid in de EU geanalyseerd:

- gezondheidstoestand en geestelijke gezondheid;

- gezondheidsgedrag;

- toegang tot gezondheidsvoorzieningen;

- seksuele en reproductieve gezondheid;

- de COVID-19-pandemie.

Description

In de gendergelijkheidsindex 2022 staan de sociaaleconomische gevolgen van de COVID-19-pandemie centraal. Binnen deze thematische focus worden de volgende aspecten geanalyseerd:

- kinderopvang

- langdurige zorg

- huishoudelijk werk

- veranderingen in flexibele arbeidsregelingen

De gegevens zijn verzameld via een enquête die in juni en juli 2021 in alle EU-lidstaten werd gehouden. Dankzij het ontwerp en het tijdpad voor gegevensverzameling leverde de enquête een compleet beeld op van de gevolgen van de COVID-19-pandemie. De enquête werd afgenomen met behulp van een internationaal webpanel met een quotum-steekproefmethode op basis van stratificatie[1]. De enquête was gericht op de algemene bevolking tussen 20 en 64 jaar. Er werden representatieve quota geformuleerd aan de hand van de Eurostat-bevolkingsstatistieken voor 2020. Na de stratificatie werd een weging toegepast om verschillen tussen de steekproef en de populatieverdeling met betrekking tot belangrijke variabelen te corrigeren en om te waarborgen dat de steekproef een getrouwe afspiegeling vormde van de sociaal-demografische opbouw van de doelpopulatie.

[1] De gegevens werden verzameld via een webenquête met het internationale panelplatform CINT als belangrijkste instrument. CINT is een internationaal platform dat verschillende internationale panels bijeenbrengt en meer dan 100 miljoen geregistreerde panelleden in meer dan 150 landen bereikt. Voor de samenstelling van de benodigde steekproef in kleine landen werden aanvullende panelaanbieders (Ipsos, Toluna, Kantar) ingeschakeld, waardoor het mogelijk werd om bij de profilering van de respondenten dezelfde uniforme vereisten te hanteren en de AVG na te leven.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2023 focuses on the socially fair transition of the European Green Deal. Its thematic focus analyses the following aspects:

- Public attitudes and behaviours on climate change and mitigation

- Energy

- Transport

- Decision-making

The data was collected through various surveys, such as the EIGE 2022 survey on gender gaps in unpaid care, individual and social activities, as well as other EU-wide surveys.1 The EIGE survey focused on gender differences in unpaid care, including links to transport, the environment and personal consumption and behaviour.

[1] The following sources were used: the EIGE survey on gender gaps in unpaid care, individual and social activities; the European Social Survey; Eurostat-LFS; EU-SILC; education statistics; and the EIGE’s WiDM.

Description

De gendergelijkheidsindex 2023 besteedt bijzondere aandacht aan de sociaal rechtvaardige transitie in het kader van de Europese Green Deal. Binnen deze thematische focus worden de volgende aspecten geanalyseerd:

- houdingen en gedragingen van het publiek ten opzichte van klimaatverandering en mitigatie

- energie

- vervoer

- besluitvorming

De gegevens zijn verzameld door middel van verschillende enquêtes, zoals de enquête van EIGE uit 2022 over de genderkloof op het gebied van onbetaalde zorg en individuele en sociale activiteiten en andere EU-brede enquêtes.1 De EIGE-enquête was gericht op sekseverschillen in de onbetaalde zorg, inclusief verbanden met vervoer, het milieu en persoonlijke consumptie en gedrag.

[1] De volgende bronnen werden gebruikt: de EIGE-enquête naar de genderkloof op het gebied van onbetaalde zorg en individuele en sociale activiteiten, de Europese sociale enquête, Eurostat-LFS, EU-SILC, onderwijsstatistieken en de WiDM van het EIGE.