Country information

Description

Progress on gender equality in Estonia since 2010

With 60.7 out of 100 points, Estonia ranks 18th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Estonia’s score is 7.2 points below the EU’s score. Since 2010, its score has increased by 7.3 points. Only a slight increase (0.9 points) was achieved on the 2017 score. Estonia is progressing towards gender equality faster than other EU Member States. Its ranking has improved by three places since 2010.

Best performance

Estonia’s scores are highest in the domains of health (81.6 points) and time (74.7 points). Its score for the latter is one of the highest among all countries (ranking 5th).

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities are most pronounced in the domain of power (36.1 points), although this score has improved since 2010 (+ 14.2 points).

Biggest improvement

Since 2010, Estonia’s scores have improved the most in the domains of power (+ 14.2 points), knowledge (+ 4.7 points) and money (+ 4.5 points).

A step backwards

Since 2010, Estonia’s score has decreased in the domain of health (– 1.1 points). Progress has stalled in the domains of work (+ 0.9 points) and time (+ 1.0 points).

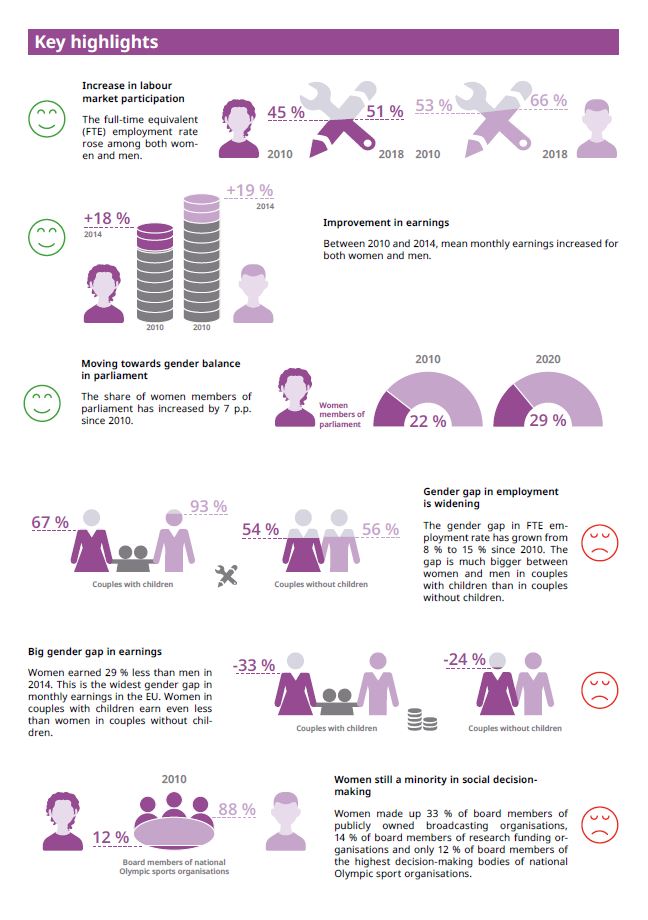

Key highlights

Positives

- The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate rose among both women and men.

- Between 2010 and 2014, mean monthly earnings increased for both women and men.

- The share of women members of parliament has increased by 7 p.p. since 2010.

Negatives

- The gender gap in FTE employment rate has grown from 8 % to 15 % since 2010. The gap is much bigger between women and men in couples with children than in couples without children.

- Women earned 29 % less than men in 2014. This is the widest gender gap in monthly earnings in the EU. Women in couples with children earn even less than women in couples without children.

- Women made up 33 % of board members of publicly owned broadcasting organisations, 14 % of board members of research funding organisations and only 12 % of board members of the highest decision-making bodies of national Olympic sport organisations.

Description

Progress in gender equality in Estonia since 2010

With 61.6 out of 100 points, Estonia ranks 17th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 6.4 points below the EU’s score. Since 2010, Estonia’s score has increased by 8.2 points and its ranking has increased by three places. These improvements have been driven primarily by higher scores in the domains of power and money. Since 2018, Estonia’s score has increased by only 0.9 points. Its ranking has not changed.

Best Performance

Estonia’s highest ranking is in the domain of time, in which it ranks 5th among all Member States with a score of 74.7 points. The country’s best performance is in the sub-domain of care activities, in which it ranks 4th with a score of 85.9 points (+ 5.2 points since 2010).

Most room for improvement

Estonia ranks 23rd in the domain of health, with a score of 82.2 points. Its ranking has dropped by two places since 2010. Estonia’s score is the lowest in the sub-domain of health behaviour in which it ranks 20th among all Member States. In the sub-domain of health access, Estonia is the last among all Member States.

Biggest improvement

Since 2010, Estonia’s ranking has improved from the 22nd to the 16th place in the domain of knowledge. Improvements in the sub-domain of educational attainment have driven the score from 51.6 points in 2010 to 57.3 points in 2019.

A step backwards

Estonia’s progress stalls in the domain of work where it scores 72.5 points and ranks 16th. Its score has slightly improved since 2010 (+ 1.3 points), but its ranking has dropped by two places since 2010.

Description

Progress in gender equality

With 61.0 out of 100 points, Estonia ranks 17th in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 7.6 points below the EU’s score. Since 2010, Estonia’s score has increased by 7.6 points, and its ranking has increased by three places. These improvements were mainly driven by higher scores in the domains of power and money. Since 2019, Estonia’s score has slightly decreased (– 0.6 points), maintaining the same ranking. A setback in the domain of power has mostly driven this decrease.

Best performance

Estonia’s ranking is the highest (5th among all Member States) in the domain of time in which the country scores 74.7 points. Within this domain, the country performs best in the sub-domain of care activities, ranking 4th with a score of 85.9 points (+ 5.2 points since 2010).

Most room for improvement

Gender inequalities are strongly pronounced in the domain of knowledge (57.4 points), in which Estonia ranks 18th. Most room for improvement is in the sub-domain of segregation, in which Estonia scores 45.8 points and ranks 25th in the EU. Since 2019, progress in the domain of knowledge has stalled (+ 0.1 points), resulting in a drop in the country’s ranking by two places. Improvements in the sub-domain of segregation (+ 1.3 points) have been balanced out by losses in the sub-domain of attainment and participation (– 1.8 points).

Biggest improvement

Since 2019, Estonia’s score has improved the most in the domain of health (+ 2.8 points), moving up the country’s ranking from the 23rd to the 20th place. These changes were driven by improvements in the sub-domain of health behaviour (+ 6.0 points), resulting in an improvement in the country’s ranking from the 20th to the 13th place in this sub-domain.

A step backwards

Since 2019, Estonia’s score has worsened in the domain of power (– 2.6 points), and its ranking has dropped from the 20th to the 21st place. This setback has been driven by higher levels of gender inequality in social and economic decision-making (– 7.0 points and – 2.3 points, respectively).

Key highlights

Focus 2022: COVID-19 in Estonia

-

Women were much more likely than men to take over childcare responsibilities

In 2021, more women than men (47 % and 23 %, respectively) spent more than four hours caring for their children aged 0–11 every day. In 2021, 49 % of women, compared to 15 % of men reported taking care of and supervising children aged 0–11 completely or mostly by themselves. The gender gap of 34 pp in the distribution of care and supervision of children aged 0–11 is among the widest in the EU.

-

Less women than men provided informal long-term care

In 2021, 26 % of women and 35 % of men reported providing informal long-term care. During the pandemic, 6 % of women compared to 17 % of men spent more than four hours a day caring for older people or people with health limitations. At the same time, men were more likely than women to rely on external institutional support, particularly day-care centres (47 %) or residential long-term facilities (44 %). In comparison, only 24 % of women relied on day-care centres and 23 % on residential long-term care facilities.

-

Less women than men provided informal long-term care

In 2021, 60 % of women and only 8 % of men reported carrying out household chores completely or mostly by themselves. Women’s engagement in housework was also likely to be more intense than men’s with 18 % of women compared to 12 % of men spending more than four hours a day on household chores.

Description

Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse areng Eestis alates 2010. aastast

Eesti soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeks on 61,6 punkti 100st, millega ta on ELis 17. kohal. Eesti punktisumma on ELi omast 6,4 punkti väiksem.

Alates 2010. aastast on Eesti punktisumma suurenenud 8,2 punkti ja tõusnud kolm kohta. See paranemine on peamiselt tulenenud suurematest punktisummadest võimu ja raha valdkonnas. Alates 2018. aastast on punktisumma paranenud ainult 0,9 punkti võrra. Eesti koht järjestuses ei ole muutunud.

Parim tulemus

Eesti on kõrgeim koht on ajavaldkonnas, kus ta on 74,7 punktiga kõigi liikmesriikide seas 5. kohal. Riigi parim tulemus on hooldustegevuste alamvaldkonnas, kus ta on 85,9 punktiga (+5,2 punkti alates 2010. aastast) 4. kohal.

Kõige rohkem arenguruumi

Eesti on kõrgeim koht on ajavaldkonnas, kus ta on 74,7 punktiga kõigi liikmesriikide seas 5. kohal. Riigi parim tulemus on hooldustegevuste alamvaldkonnas, kus ta on 85,9 punktiga (+5,2 punkti alates 2010. aastast) 4. kohal.

Suurim paranemine

Alates 2010. aastast on Eesti koht järjestuses tõusnud 22. kohalt 16. kohale teadmiste valdkonnas. Hariduse omandamise alamvaldkonnas on punktisumma suurenenud 57,3 punktilt 2010. aastal 57,3 punktini 2019. aastal.

Samm tagasi

Eesti areng on seiskunud töövaldkonnas, kus tal on 72,5 punkti, millega tal on järjestuses 16. koht. Alates 2010. aastast on punktisumma mõnevõrra paranenud (+1,3 punkti), kuid koht järjestuses on alates 2010. aastast langenud kahe koha võrra.

Description

Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse muutumine

Eesti soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeks on 61,0 punkti 100st, millega on Eesti ELis 17. kohal. Eesti punktisumma on ELi summast 7,6 punkti väiksem. Alates 2010. aastast on suurenenud Eesti punktisumma 7,6 punkti ja riik on tõusnud kolm kohta. See suurenemine on tulenenud peamiselt suurematest punktisummadest võimu ja raha valdkonnas. Alates 2019. aastast on Eesti punktisumma veidi vähenenud (–0,6 punkti), kuid koht on jäänud samaks. Vähenemine tuleneb peamiselt tagasilangusest võimu valdkonnas.

Parim tulemus

Eesti koht on kõrgeim (kõigi liikmesriikide seas viies) aja valdkonnas, kus riigil on 74,7 punkti. Selles valdkonnas on riigil parimad tulemused hoolduse alamvaldkonnas, kus riik on 85,9 punktiga neljandal kohal (+5,2 punkti võrreldes 2010. aastaga).

Kõige rohkem arenguruumi

Soolist ebavõrdsust esineb palju teadmiste valdkonnas (57,4 punkti), kus Eesti on 18. kohal. Kõige rohkem arenguruumi on segregatsiooni alamvaldkonnas, kus Eesti on 45,8 punktiga ELis 25. kohal. Võrreldes 2019. aastaga on suurenemine teadmiste valdkonnas peatunud (+0,1 punkti), mistõttu riik on langenud kahe koha võrra. Kuigi segregatsiooni alamvaldkonnas on punktisumma suurenenud (+1,3 punkti), on haridustaseme ja hariduses osalemise alamvaldkondades summa vähenenud (–1,8 punkti).

Suurim suurenemine

Alates 2019. aastast on kõige rohkem suurenenud Eesti punktisumma tervise valdkonnas (+2,8 punkti), millega riik on tõusnud 23. kohalt 20. kohale. Need muudatused on tingitud suurenemisest tervisekäitumise alamvaldkonnas (+6,0 punkti), mistõttu riik tõusis selles alamvaldkonnas 20. kohalt 13. kohale.

Samm tagasi

Alates 2019. aastast on vähenenud Eesti punktisumma võimu valdkonnas (–2,6 punkti) ja riik on langenud 20. kohalt 21. kohale. Tagasilangus on tingitud suuremast soolisest ebavõrdsusest sotsiaal- ja majandusotsuste tegemisel (vastavalt –7,0 ja –2,3 punkti).

Key highlights

Olulised punktid

-

Naised hooldavad lapsi palju tõenäolisemalt kui mehed

2021. aastal oli rohkem naisi kui mehi (vastavalt 47 % ja 23 %), kes hoolitsesid oma 0–11-aastaste laste eest üle nelja tunni päevas. 2021. aastal teatas 49 % naistest ja 15 % meestest, et hoolitsevad täielikult või peamiselt ise oma 0–11-aastaste laste eest ja valvavad nende järele. Sooline ebavõrdsus 34 pp on 0–11-aastaste laste hoolduse ja järelevalve jaotuses üks suurimaid ELis.

-

Mitteametlikku pikaajalist hooldust pakkus vähem naisi kui mehi

2021. aastal teatas 26 % naistest ja 35 % meestest, et neil on mitteametlikud pikaajalise hoolduse kohustused. Pandeemia ajal hoolitses 6 % naistest ja 17 % meestest eakate või tervisepiirangutega inimeste eest üle nelja tunni päevas. Samal ajal kasutasid mehed naistest suurema tõenäosusega asutuste, eriti päevakeskuste (47 %) või pikaajaliste hooldekodude (44 %) pakutavat välist abi. Samas kasutas naistest päevakeskuste abi ainult 24 % ja pikaajaliste hooldekodude abi 23 %.

-

Naiste ja meeste vahel jagunesid kodutööd väga ebavõrdselt

2021. aastal teatas 60 % naistest ja ainult 8 % meestest, et teevad kodutöid täielikult või peamiselt ise. Samuti oli kodutööde tegemine tõenäolisemalt intensiivsem naistel kui meestel: kodutöid tegid rohkem kui neli tundi päevas 18 % naistest ja 12 % meestest.

Description

Progress in gender equality

With 60.2 points out of 100, Estonia ranks 22nd in the EU on the Gender Equality Index. Its score is 10.0 points below the score for the EU as a whole.1

Since 2010, Estonia’s score has increased overall by 6.8 points, mainly due to improvements in the domain of power (+ 11.1 points). Since 2020, Estonia’s score has decreased by 0.8 points. This is mainly due to a backsliding in the domain of time (– 10.3 points). Estonia has also registered a 1.0-point decrease in the domain of power, mainly due to a decrease in the sub-domain of economic decision-making.

Due to slower progress compared with other EU countries, Estonia’s overall ranking has fallen five places since 2020.

Best performance

Estonia scores highest (85.1 points) in the domain of health, where the country ranks 18th in the EU, moving up two places since 2020. Within this domain, the country ranks highest in the sub-domain of health behaviour (76.1 points), where it ranks 13th in the EU. Since 2020, Estonia has made improvements in the sub-domain of health access (+ 94.7 points), moving up four places to the 23rd place.

Most room for improvement

Estonia ranks among the lowest in the EU (in 22nd place) in the domain of knowledge, with a score of 57.8 points. The country’s progress in this domain has almost stalled (+ 0.4 points since 2020), resulting in a drop in the ranking by four places due to other Member States making faster progress. The sub-domain that shows the greatest room for improvement is that of segregation in education, in which Estonia scores 46.3 points, ranking 24th in the EU.

Biggest improvement

Since 2020, the biggest improvement in Estonia’s score has been in the domain of work (+ 4.8 points), with the country moving up this ranking from 17th place to 7th. This is the fourth largest increase among all Member States in the domain of work. Progress in this domain has largely been driven by improvements in the sub-domain of segregation and quality of work (+ 6.5 points since 2020), in which Estonia rose three places to currently stand at 17th.

A step backwards

Since 2020, Estonia’s score in the domain of time has decreased (– 10.3 points), leading to a drop in this ranking from the 5th place to the 16th. This setback is due to large falls in the sub-domain of social activities (– 20.0 points), one of the biggest decreases in the EU. As a result, Estonia has dropped 18 places to rank 25th out of all Member States in this ranking.

Convergence

Upward convergence in gender equality describes increasing equality between women and men in the EU, accompanied by a decline in variations between Member States. This means that countries with lower levels of gender equality are catching up with those with the highest levels, thereby reducing disparities across the EU. Analysis of convergence patterns in the Gender Equality Index shows that disparities between Member States decreased over the period 2010–2021, and that EU countries continue their trend of upward convergence.

Looking more closely at the performance of each Member State, patterns can be identified that reflect a relative improvement or slipping back in the Gender Equality Index score of each Member State in relation to the EU average.

Estonia is improving at a slower pace than other Member States. Its Gender Equality Index score has improved, but is consistently and considerably lower than the EU average. Progress towards gender equality has been slow, and the gap between Estonia and the EU average has widened over time.

Key highlights

Focus 2023: The European Green Deal

-

Women and men in Estonia feel less responsibility for trying to reduce climate change than in other Member States

In Estonia, noticeably fewer women (37 %) and men (32 %) felt responsible for reducing climate change than women and men on average in the EU (62 % and 61 %, respectively) in 2018. This attitude was also reflected in their behaviours. Only 16 % of women and 14 % of men in Estonia regularly avoided animal products in 2022, which is much lower than the EU average (31 % and 23 %, respectively). When it comes to choosing environmentally friendly options when doing housework, only 35 % of both Estonian women and men used them regularly, in contrast with 59 % of women and 53 % of men in the EU.

-

Fewer people in Estonia struggled to heat their homes compared with the EU average

Even prior to the full impact of the ongoing energy crisis, many people in the EU were struggling to pay for energy and heating. In Estonia, older women and men (both 3 %), women and men with low educational status (both 3 %) and women and men with disabilities (both 3 %) struggled the most to keep their homes adequately warm in 2021. The share of people who had problems in this respect is considerably lower in Estonia than the EU average.

-

Women are highly underrepresented in the energy and transport sectors and decision-making in Estonia

In 2022, the share of women working in the transport and energy sectors in Estonia was 21 % and 18 % 2, respectively. Women were also considerably underrepresented in decision-making roles, with only 18 % of decision-makers in parliamentary committees focusing on the environment and climate change being women. When it comes to senior administrators in national ministries dealing with environment and climate change in Estonia, women represented 41 % of decision-makers in 2022.

Description

Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse edenemine

Eesti soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeks on 60,2 punkti 100st, mis seab Eesti ELi liikmesriikide seas 22. kohale. Eesti punktisumma on 10,0 punkti võrra väiksem ELi kui terviku punktisummast.1

Alates 2010. aastast on Eesti üldine tulemus tõusnud 6,8 punkti võrra, peamiselt tänu paranemisele võimu valdkonnas (+ 11,1 punkti). Alates 2020. aastast on Eesti punktisumma langenud 0,8 punkti võrra. See on peamiselt tingitud tagasilangusest aja valdkonnas (– 10,3 punkti). Eestis on toimunud 1,0-punktine langus ka võimu valdkonnas, peamiselt languse tõttu majanduslike otsuste tegemise alavaldkonnas.

Teiste ELi riikidega võrreldes aeglasema arengu tõttu on Eesti alates 2020. aastast langenud üldises pingereas viis kohta.

Parimad tulemused

Eesti tulemused on kõrgeimad (85,1 punkti) tervishoiu valdkonnas, kus riik on ELis 18. kohal, olles liikunud alates 2020. aastast kaks kohta ülespoole. Selles valdkonnas on riik kõige kõrgemal tervisekäitumise alavaldkonnas (76,1 punkti), olles ELis 13. kohal. Alates 2020. aastast on Eesti teinud edusamme tervishoiuteenuste kättesaadavuse alavaldkonnas (+ 94,7 punkti), tõustes nelja koha võrra 23. kohale.

Kõige rohkem arenguruumi

Eesti on ELi madalaimate seas teadmiste valdkonnas (22. kohal) 57,8 punktiga. Riigi edusammud selles valdkonnas on peaaegu peatunud (+ 0,4 punkti alates 2020. aastast), mille tulemuseks langus edetabelis nelja koha võrra, sest teised liikmesriigid on teinud kiiremaid edusamme. Kõige rohkem arenguruumi on hariduse segregatsiooni alavaldkonnas, kus Eesti on 46,3 punktiga ELis 24. kohal.

Suurim tulemuste paranemine

Alates 2020. aastast on Eesti tulemus kõige rohkem paranenud töö valdkonnas (+ 4,8 punkti), kus riik on tõusnud 17. kohalt 7. kohale. See on kõigi liikmesriikide seas neljas suurim kasv töö valdkonnas. Edusammud selles valdkonnas on suures osas saavutatud töö segregatsiooni ja kvaliteedi alavaldkonna paranemisega (+ 6,5 punkti alates 2020. aastast), kus Eesti tõusis kolm kohta ja on praegu 17. kohal.

Samm tagasi

Alates 2020. aastast on Eesti punktitulemus aja valdkonnas vähenenud (– 10,3 punkti), mille tõttu on Eesti langenud selles pingereas 5. kohalt 16. kohale. See tagasilangus on tingitud suurest langusest ühiskondlike tegevuste alavaldkonnas (– 20,0 punkti), mis on üks suurimaid langusi ELis. Seetõttu on Eesti langenud 18 kohta ja on selles edetabelis kõigist liikmesriikidest 25. kohal.

Lähenemine

Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse ülespoole suunatud lähenemine kirjeldab naiste ja meeste võrdõiguslikkuse suurenemist ELis, millega kaasneb erinevuste vähenemine liikmesriikide vahel. See tähendab, et madalama soolise võrdõiguslikkuse tasemega riigid jõuavad kõrgeima tasemega riikidele järele, vähendades seeläbi ebavõrdsust kogu ELis. Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeksi lähenemismudelite analüüs näitab, et aastatel 2010–2021 liikmesriikidevahelised erinevused vähenesid ja ELi riigid jätkavad ülespoole lähenemise suundumust.

Iga liikmesriigi tulemusi lähemalt vaadates võib tuvastada mustrid, mis kajastavad iga liikmesriigi soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeksi suhtelist paranemist või tagasilangust võrreldes ELi keskmisega.

Eestis paraneb indeksi skoor aeglasemalt kui teistes liikmesriikides. Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeksi skoor on paranenud, kuid see on järjekindlalt ja märkimisväärselt madalam kui ELi keskmine. Edusammud soolise võrdõiguslikkuse suunas on olnud aeglased ning Eesti ja ELi keskmise vaheline lõhe on aja jooksul suurenenud.

Key highlights

Olulised punktid

-

Eesti naised ja mehed tunnevad vähem vastutust kliimamuutuste vähendamise püüdluste eest kui teistes liikmesriikides

Eestis tundsid 2018. aastal naised (37%) ja mehed (32%) end märgatavalt vähem kliimamuutuste vähendamise eest vastutavana kui naised ja mehed ELis keskmiselt (vastavalt 62% ja 61%). See suhtumine kajastus ka nende käitumises. Vaid 16% Eesti naistest ja 14% meestest vältisid 2022. aastal regulaarselt loomseid tooteid, mis on palju madalam kui ELi keskmine (vastavalt 31% ja 23%). Mis puudutab keskkonnasõbralike variantide valimist kodutööde tegemisel, siis neid kasutas regulaarselt vaid 35% Eesti naistest ja meestest, erinevalt 59% naistest ja 53% meestest ELis.

-

ELi keskmisega võrreldes oli Eestis vähem inimesi, kellel oli raskusi oma kodu kütmisega

Isegi enne praeguse energiakriisi täielikku mõju oli paljudel ELis elavatel inimestel raskusi energia ja kütte eest tasumisega. Eestis oli 2021. aastal kõige rohkem raskusi oma kodu piisavalt soojana hoidmisega eakatel naistel ja meestel (mõlemad 3%), madala haridustasemega naistel ja meestel (mõlemad 3%) ning puuetega naistel ja meestel (mõlemad 3%). Nende inimeste osakaal, kellel oli selles vallas probleeme, on Eestis tunduvalt väiksem kui ELis keskmiselt.

-

Naised on Eestis energeetika- ja transpordisektoris ning otsuste tegemisel tugevalt alaesindatud

2022. aastal oli Eestis transpordi- ja energeetikasektoris töötavate naiste osakaal vastavalt 21% ja 18% 2. Naised olid märkimisväärselt alaesindatud ka otsuste tegemise rollis: vaid 18% keskkonna- ja kliimamuutustega tegelevate parlamendikomisjonide otsustajatest olid naised. Mis puudutab Eesti keskkonna ja kliimamuutustega tegelevate riiklike ministeeriumide vanemametnikke, siis moodustasid naised 2022. aastal otsustajatest 41%.

Domain information

Description

In the domain of work, the increased participation of women and men in employment contributed to an increase in the score.

The employment rate (20-64) is 73 % for women versus 81 % for men. The total employment rate is 77 %, and Estonia has reached its national target of the Europe 2020 strategy (EU2020) (76 %).

The gender gap in the employment rate doubles when the number of hours worked is taken into account. The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate of women is around 50 %, compared to 64 % for men.

Among couples with children, the FTE employment rate for women is 61 % compared to 87 % for men. The gender gap is much wider compared to that of couples without children, where almost no gender differences are present. The FTE employment rate is also wider for men than women aged 25-49 (82 % versus 71 %, respectively). The FTE employment rate increases and the gender gap shrinks as education levels rise.

15 % of women work part-time, compared to 7 % of men. On average, women work 37 hours per week, compared to 40 hours for men. 8 % of working-age women versus 0.3 % of working-age men are either inactive or work part-time due to care responsibilities.

Gender segregation in the labour market is a reality for both women and men. Nearly 26 % of women compared to 6 % of men work in education, human health and social work activities (EHW). About four times more men (39 %) than women (10 %) work in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations. There are twice as many highly educated women working in education, health and welfare (EHW) as women with a low level of education.

Description

The score in the domain of money has increased. Gender equality has improved in earnings and income, but has regressed in poverty and in the distribution of wealth.

Mean monthly earnings of women and men have increased, but so has the gender gap. Women earn around 29 % less than men per month.

The gender gap in earnings is greater among lone parents, people aged 25-49, highly educated people and foreign-born people. In each group, women always earn less than men. The net incomes of women and of men have doubled.

The population of women and men at risk of poverty has increased. The risk affects women more heavily than men (24 % of women and 19 % of men). Nearly 40 % of women aged 65+ are at risk of poverty, compared to 18 % of men the same age.

Inequalities in income distribution have increased. The gender pay gap is 27 % to the detriment of women. In 2012, women had lower pensions than men and the gender gap was 5 %. The EU-28 averages are 16 % and 38 %, respectively.

Description

The score in the domain of knowledge has improved.

From 2005 to 2015, the number of tertiary graduates increased significantly, mostly among women. 41 % of women compared to 25 % of men have a tertiary degree. This gap, to the disadvantage of men, is widening.

Only 31 % of women with disabilities have attained tertiary education, compared to 45 % of women without disabilities. This is a bigger gender gap in tertiary education attainment than among men with disabilities (20 %), compared to men without disabilities (28 %).

Estonia has already met its national EU2020 target to have 40 % of people aged 30-34 obtain tertiary education. The current rate is 45 %.

Women’s participation in lifelong learning has increased, but for men it has stalled.

Gender segregation in knowledge remains a major challenge. 41 % of women students are concentrated in the fields of education, health and welfare, humanities and art, compared to only 14 % of men.

Description

In the domain of time, the score barely changed. It remains among the highest in the EU-28. This is due to a more equal sharing of care activities among women and men. However, gender inequalities persist. Challenges remain in the division of time allocated to social activities between women and men.

Women take on more responsibilities for caring for their family. 35 % of women care for and educate their family members for at least 1 hour, compared to 31 % of men. Involvement in care responsibilities increases with a person’s level of education, especially for men. Among couples with children, more women (92 %) than men (66 %) are involved in daily care activities.

76 % of women compared to 47 % of men do cooking and housework every day for at least 1 hour. The gender gap has slightly increased and is greater among people in couples with children, with 90 % of women and 51 % of men doing cooking and housework on a daily basis.

Inequality in time-sharing at home also extends to social activities. Men are slightly more likely than women to participate in sporting, cultural and leisure activities outside the home (38 % versus 34 %, respectively).

Participation in voluntary or charitable activities is slightly higher for women than it is for men. This level of engagement has decreased for both, but has declined for men at a faster rate.

21 % of children under the age of three and 93 % of children between the age of three and school age are enrolled in childcare. Estonia has met only the second of the two ‘Barcelona targets’, which are to have at least 33 % of children below three and 90 % of children between three and school age in childcare.

Description

The score in the domain of power has increased, even if at a slower pace compared to most EU-28 countries. It remains the domain with the lowest score in Estonia, mostly due to the lack of women in the areas of economic and social power.

The increase in the sub-domain of political power is because of an improved gender balance in parliament. The percentage of women members rose from 19 % to 23 % from 2005 to 2015. More women also became government ministers (22 %).

Publicly listed companies had a large decrease in the percentage of women on their corporate boards: from 14 % in 2005 to 8 % in 2015. On the other hand, women have gained more decision-making positions in the central bank, to represent 18 % of board members (up from 13 %).

There are no women on the boards of research-funding organisations. On the other hand, women make up a quarter of the board members of publicly owned broadcasting organisations. In sport, women comprise just 11 % of members of the highest decision-making bodies of national Olympic sport organisations.

Description

The scores in the domain hardly changed. Health status has improved, while access to services has gone down.

The sub-domain of status measures perceived health, life expectancy and healthy life years. The gaps between women and men have narrowed in all three areas.

Life expectancy has increased for both women and men. On average women live nearly 9 years longer than men. Women also have more healthy life years, but the difference is much smaller (2 years).

50 % of women and 54 % of men assess their health as ‘good’ or ‘very good’. Women and men in couples with children are twice as satisfied with their health as women and men in couples without children.

The drop in the sub-domain of access is due to a rise in unmet medical needs: 16 % for women and 13 % for men. This has been partially offset by a decrease in unmet dental needs, which is 13 % for women and 11 % for men.

More than half of men smoke or drink excessively, compared to around a quarter of women. Women and men engage equally in healthy behaviour (doing physical activities and/or consuming fruit and vegetables).

Description

Violence against women is included in the Gender Equality Index as a satellite domain. This means that the scores of the domain of violence do not have an impact on the final score of the Gender Equality Index. From a statistical perspective, the domain of violence does not measure gaps between women and men as core domains do. Rather, it measures and analyses women’s experiences of violence. Unlike other domains, the overall objective is not to reduce the gaps of violence between women and men, but to eradicate violence completely.

A high score in the Gender Equality Index means a country is close to achieving a gender-equal society. However, in the domain of violence, the higher the score, the more serious the phenomenon of violence against women in the country is. On a scale of 1 to 100, 1 represents a situation where violence is non-existent and 100 represents a situation where violence against women is extremely common, highly severe and not disclosed. The best-performing country is therefore the one with the lowest score.

Estonia’s score for the domain of violence is 25.8, which is slightly lower than the EU average.

In Estonia, 34 % of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence since the age of 15.

5 % of women who have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by any perpetrator in the past 12 months have not told anyone. This rate is lower than the EU average of 13 %.

At societal level, violence against women costs Estonia an estimated EUR 590 million a year through lost economic output, service utilisation and personal costs (1).

The domain of violence is made up of three sub-domains: prevalence, which measures how often violence against women occurs; severity, which measures the health consequences of violence; and disclosure, which measures the reporting of violence.

[1] This is an exercise done at EU level to estimate the costs of the three major dimensions: services, lost economic output and pain and suffering of the victims. The estimates were extrapolated to the EU from a United Kingdom case study, based on population size. EIGE, Estimating the costs of gender-based violence in the European Union, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2014, p. 142.

Description

Estonia’s score in the domain of work is 71.5, showing slight progress of 0.5 points since 2005 (- 0.6 points since 2015), with increased participation of women and men in employment.

Estonia ranks second in the EU in the sub-domain of participation. The employment rate (of people aged 20-64) is 76 % for women and 84 % for men. With the overall employment rate of 80 %, Estonia has reached its national EU 2020 employment target of 76 %. The full-time equivalent (FTE) employment rate rose from 48 % to 51 % for women and from 58 % to 65 % for men between 2005 and 2017, widening the gender gap. Between women and men in couples with children, the gap is far greater than in couples without children (26 percentage points (p.p.) and 1 p.p.). The FTE employment rate increases and the gender gap shrinks as education levels rise.

About 15 % of women work part-time, compared to 7 % of men. On average, women work 37 hours per week and men work 40 hours. The uneven concentration of women and men in different sectors of the labour market remains an issue: 25 % of women work in education, health and social work, compared to 4 % of men. Fewer women (10 %) than men (40 %) work in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations.

Description

Estonia’s score in the domain of money is 69.4, showing progress of 11 points since 2005 (+ 2.7 points since 2015), with significant improvements in the financial situations of both women and men.

Despite increases in mean monthly earnings of both women (+ 53 %) and men (+ 48 %) from 2006 to 2014, the gender gap persists: women earn 29 % less than men. This is the widest gender gap in the EU. In couples with children, women earn 38 % less than men, while in couples without children, women earn 22 % less. Gender gaps are prevalent across all levels of education: women with low, medium and high education earn around a third less than men.

The risk of poverty increased between 2005 and 2017. Around 25 % of women (+ 6 p.p.) and 19 % of men (+ 3 p.p.) are at risk. People facing the highest risks of poverty are: single people, especially women (58 % of women compared to 45 % of men), women aged 65 and over (48 %), women with low education (44 %) and women with disabilities (40 %). Inequalities in income distribution slightly decreased among and between women and men from 2005 to 2017. Women earn on average 74 cents for every euro a man makes per hour, resulting in a gender pay gap of 26 %. The gender pension gap is 3 %.

Description

Estonia’s score in the domain of knowledge is 55.5, with a 6-point increase since 2005 (+ 2.3 points since 2015). Estonia ranks 22nd in the EU in the domain of knowledge. There are improvements in both sub-domains of attainment and participation, and segregation.

The share of women tertiary graduates increased (from 32 % to 42 %), while the share of men also increased (from 23 % to 26 %), widening the gender gap between 2005 and 2017. The gender gap in attainment is higher for lone parents (22 p.p.), and between women and men aged 25-49 (21 p.p.), to the detriment of men. Estonia has reached its national EU 2020 target of having 40 % of people aged 30-34 obtain tertiary education. The current rate is 47 % (58 % for women and 38 % for men). Participation in formal and non-formal education and training also increased from 15 % to 21 % for women and from 16 % to 18 % for men, between 2005 and 2017. Estonia’s participation rate in lifelong learning is the eighth highest in the EU.

Despite an increase in the sub-domain score, the uneven concentration of women and men in different study fields in tertiary education is a challenge for Estonia: 42 % of women students and 16 % of men students study education, health and welfare, and humanities and art.

Description

Estonia’s score in the domain of time has not changed since the last edition of the Index, because new data is not available. The next data update for this domain is expected in 2021. More frequent time-use data would help to track progress in this domain.

Estonia’s score in the domain of time is 74.7. It ranks fifth in the EU. Since 2005, inequalities have decreased in the distribution of time spent on care activities. Women take on more responsibilities in caring for their family: 35 % of women care for and educate their family members for at least one hour a day, compared to 31 % of men. Among couples with children, more women (92 %) than men (66 %) are involved in daily care activities. Around 76 % of women compared to 47 % of men do cooking and housework every day for at least one hour. This gender gap is even wider among people in couples with children.

Fewer women (34 %) than men (38 %) participate in sporting, cultural or leisure activities outside the home. Slightly more women (13 %) than men (11 %) are involved in voluntary or charitable activities, with declining levels of engagement for both.

Description

Estonia’s score in the domain of power is 34.6, with progress of 12.1 points since 2005 (+ 6.4 points since 2015). This is the lowest score for Estonia across all domains and ranks 20th in the domain of power in the EU. The increase in score is driven by improvements in the sub-domains of both political and social power, while progress in the sub-domain of economic power has stalled.

The share of women increased significantly in political decision-making. Women comprise 28 % of ministers in Estonia (compared to 14 % in 2005), and 29 % of members of parliament are women (compared to 19 % in 2005). The share of women among members of local councils is 31 %. The share of women on the boards of the largest publicly listed companies decreased from 13 % to 8 % between 2005 and 2018, while the share of women on the board of the central bank increased from 13 % to 18 %.

The share of women among board members of publicly owned broadcasting organisations is 50 %, which is the second highest rate in the EU. Women comprise 14 % of board members of research-funding organisations and just 9 % of board members of the highest decision-making bodies of national Olympic sports organisations.

Description

Estonia’s score in the domain of health is 81.9, with no significant change since 2005 (+ 0.4 points since 2015). Health status has improved in terms of gender equality, while progress has stalled in health services. There is no new data for health behaviour.

The overall level of health satisfaction in Estonia slightly decreased from 51 % to 50 % for women and 57 % to 56 % for men between 2005 and 2017. Health satisfaction increases with a person’s level of education and decreases in proportion to their age. Women with low education levels and women aged 65 or over have even lower levels of health satisfaction, compared to men in the same groups. Both life expectancy and healthy life years increased for both women and men, between 2005 and 2016. Women on average live nine years longer than men (82 years compared to 73 years). On average, women have 59 years and men have 54 years of healthy life (compared to 52 and 48 years in 2005).

Adequate access to medical care has decreased overall while access to dental care has increased since 2005. Around 16 % of women and 11 % of men report unmet medical needs (compared to 9 % in 2005). About 8 % of women and 6 % of men report unmet needs for dental examinations (compared to 16 % and 15 % in 2005). More women and men with disabilities report unmet needs for medical care (22 % and 18 %), compared to those without disabilities (12 % and 8 %).

Description

Why is there no score for the violence domain?

There is no new data to update the score for violence, which is why no figure is given. Eurostat is currently coordinating an EU-wide survey on gender-based violence, with results expected in 2023. EIGE will launch a second round of administrative data collection on intimate partner violence, rape and femicide in 2022. Both data sources will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024. Unlike the other domains of the Index, the domain of violence does not measure differences between women’s and men’s situations; rather, it examines women’s experiences in violence (prevalence, severity and disclosure). The overall objective is not to reduce the gaps in violence between women and men, but to eradicate violence completely.

Data gaps mask the true scale of violence

The EU needs comprehensive, up-to-date and comparable data to develop effective policies that combat violence against women.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, women in violent relationships were stuck at home and exposed to their abuser for long periods of time, putting them at greater risk of domestic violence. Even without a pandemic, women face the greatest danger from people they know.

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on violence against women and domestic violence. Estonia signed the Istanbul Convention in December 2012 and ratified it in October 2017. The treaty entered into force in February 2018.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to Estonia in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on mobility and increased isolation exposed women to a higher risk of violence committed by an intimate partner. While the full extent of violence during the pandemic is difficult to assess, media and women’s organisations have reported a sharp increase in the demand for services for women victims of violence. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated pre-existing gaps in the prevention of violence against women and the provision of adequately funded victim support services.

Eurostat is currently coordinating a survey on gender-based violence in the EU but not all Member States are taking part. EIGE, together with the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), will collect data for the remaining countries to have an EU-wide comparable data on violence against women. Data collection will be completed in 2023, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024.

Violence at a glance

- Femicide

In 2018, over 600 women were murdered by an intimate partner, a family member or a relative in 14 EU Member States, according to official reports. Estonia does not provide comparable data on intentional homicide.

Source: Eurostat, 2018 - Physical and/or sexual violence

64 % of women who experienced physical and/or sexual violence, experienced it in their own home.

9 % of lesbian women and 4 % of bisexual women were physically or sexually attacked in the past five years for being LGBTI.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey and LGBTI Survey II, 2019 - Harassment

45 % of women experienced harassment in the past five years, and 31 % in the past 12 months.

45 % of women with disabilities experienced harassment in the past five years, and 30 % in the past 12 months.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey, 2019 - Cyberviolence

15 % of women were subjected to cyber harassment in the past five years, and 10 % in the past 12 months.

Among women aged 16-29, 32 % experienced cyber harassment in the past five years, and 17 % in the past 12 months.

Source: FRA’s Fundamental Rights Survey, 2019 - Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

No data available.

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Estonia signed the Istanbul Convention in December 2014 and ratified it in October 2017. The treaty entered into force in February 2018.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to Estonia in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

Femicide

In 2020, 788 women were murdered by an intimate partner, a family member or a relative in 17 EU Member States, according to official reports. Estonia does not provide comparable data on intentional homicide.

Source: Eurostat, 2020

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. Estonia signed the Istanbul Convention in December 2014 and ratified it in October 2017. The treaty entered into force in February 2018.

EIGE/FRA survey

The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) will carry out a survey on violence against women (VAW II) in eight EU Member States (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), which will complement the Eurostat-led data collection on gender-based violence and other forms of interpersonal violence (EU-GBV) in the remaining countries. The use of a unified methodology will ensure the availability of comparable data across all EU Member States. Data collection will be completed in 2023, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024 and its thematic focus on violence against women.

Description

Tõendite puudumine naistevastase vägivalla hindamiseks

Eesti punktisummat ei ole esitatud vägivalla valdkonnas kogu ELi hõlmavate võrdlusandmete puudumise tõttu.

COVID-19 pandeemia ajal põhjustasid liikuvuspiirangud ja eraldatuse suurenemine naistele suurema riski seoses vägivallaga intiimpartneri poolt. Kuigi vägivalla kogu ulatust pandeemia ajal on raske hinnata, on meedia ja naisorganisatsioonid teatanud naistest vägivallaohvritele osutatavate teenuste nõudluse järsust suurenemisest. Samal ajal on COVID-19 pandeemia paljastanud ja süvendanud naistevastase vägivalla ennetamise ja piisavate ohvriabiteenuste pakkumise lünki.

Eurostat koordineerib praegu uuringut soolise vägivalla kohta ELis, kuid selles ei osale kõik liikmesriigid. EIGE kogub koos Euroopa Liidu Põhiõiguste Ametiga ülejäänud riikide andmeid, et saada kogu ELi hõlmavad võrdlusandmed naistevastase vägivalla kohta. Andmete kogumine lõpeb 2023. aastal ja tulemusi kasutatakse 2024. aasta soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeksi vägivalla valdkonna ajakohastamiseks.

Vägivallast lühidalt

- Naiste tapmine

Vastavalt ametlikele teadetele mõrvati 2018. aastal üle 600 naise 14 liikmesriigis intiimpartneri, perekonnaliikme või sugulase poolt. Eesti ei ole esitanud võrdlusandmeid tahtlike tapmiste kohta.

Allikas: Eurostat, 2018. - Füüsiline ja/või seksuaalne vägivald

64% füüsilist ja/või seksuaalset vägivalda kogenud naistest koges seda oma kodus.

Viimasel viiel aastal rünnati füüsiliselt või seksuaalselt 9% lesbidest ja 4% biseksuaalsetest naistest nende LGBTI-sättumuse tõttu.

Allikas: Euroopa Liidu Põhiõiguste Amet – põhiõiguste uuring ja LGBTI uuring II, 2019 - Ahistamine

Viimasel viiel aastal koges ahistamist 45% naistest ja viimasel 12 kuul 31 %.

Viimasel viiel aastal koges ahistamist 45% puudega naistest ja viimasel 12 kuul 30%.

Allikas: Euroopa Liidu Põhiõiguste Amet – põhiõiguste uuring, 2019 - Kübervägivald

Viimasel viiel aastal koges kübervägivalda 15% naistest ja viimasel 12 kuul 10%.

Viimasel viiel aastal koges 16–29 aastastest naistest küberahistamist 32% ja viimasel 12 kuul 17%.

Allikas: Euroopa Liidu Põhiõiguste Amet – põhiõiguste uuring, 2019 - Naiste suguelundite moonutamine

Andmed puuduvad.

Istanbuli konventsioon: hetkeseis

Istanbuli konventsioon on kõige terviklikum naistevastase vägivalla ja perevägivalla ennetamise ja selle vastu võitlemise rahvusvaheline inimõiguste leping. Eesti allkirjastas Istanbuli konventsiooni 2014. aasta detsembris ja ratifitseeris selle 2017. aasta oktoobris. Leping jõustus 2018. aasta veebruaris.

Description

Puuduvad tõendid, et hinnata naistevastast vägivalda

Eest punktisumma vägivalla valdkonnas puudub, sest puuduvad võrreldavad kogu ELi hõlmavad andmed.

Naiste tapmine

Vastavalt ametlikele teadetele mõrvati 2020. aastal 17 liikmesriigis 788 naist intiimpartneri, perekonnaliikme või sugulase poolt. Eesti ei ole esitanud võrdlusandmeid tahtlike tapmiste kohta.

Allikas: Eurostat, 2020.

Istanbuli konventsioon: hetkeseis

Istanbuli konventsioon on kõige terviklikum naistevastase vägivalla ja perevägivalla ennetamise ja selle vastu võitlemise rahvusvaheline inimõiguste leping. Eesti allkirjastas Istanbuli konventsiooni 2014. aasta detsembris ja ratifitseeris selle 2017. aasta oktoobris. Leping jõustus 2018. aasta veebruaris.

EIGE/FRA uuring

Euroopa Liidu Põhiõiguste Amet (FRA) ja Euroopa Soolise Võrdõiguslikkuse Instituut (EIGE) korraldavad kaheksas ELi liikmesriigis (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE) naistevastase vägivalla uuringu (VAW II), mis täiendab ülejäänud riikides soolise vägivalla ja muude isikutevahelise vägivalla vormide andmete kogumist, mida juhib Eurostat. Ühtlustatud metoodika kasutamisega tagatakse võrreldavate andmete kättesaadavus kõigis ELi liikmesriikides. Andmete kogumine lõpeb 2023. aastal ja tulemustega ajakohastatakse 2024. aasta soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeksi vägivalla valdkonda ja selle naistevastase vägivalla teemasuunda.

Description

A lack of evidence to assess violence against women

No score is given to Estonia in the domain of violence, due to a lack of comparable EU-wide data.

Femicide

In 2021, 720 women were murdered by an intimate partner, family member or relative in 17 EU Member States, according to official reports. Estonia does not provide comparable data on

Source: Eurostat, 2021

Violence at a glance

-

Intimate partner violence

In Estonia, 41 % of women who have ever been in a relationship have experienced violence by an intimate partner during their adult life. In total, 22 % have experienced physical violence (including threats) or sexual violence, while 39 % have experienced psychological violence. Around 6 % have experienced intimate partner violence during the last 12 months, while 15 % have experienced it in the last five years.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

-

Sexual harassment at work

In Estonia, around 1 in 3 women who have ever worked have experienced sexual harassment at work. Up to 4 % of women have experienced sexual harassment at work during the last 12 months, while 12 % have experienced it in the last 5 years.

Source: Eurostat, 2021

Istanbul Convention: state of play

The Istanbul Convention is the most comprehensive international human rights treaty on preventing and combatting violence against women and domestic violence. Estonia signed the Istanbul Convention in December 2014 and ratified it in October 2017. The Convention entered into force in Estonia in February 2018.

The European Council approved the EU’s accession to the Istanbul Convention on 1 June 2023.

EIGE/FRA survey on violence against women

The Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) will carry out a survey on violence against women (VAW II) in eight EU Member States (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE), which will complement the Eurostat-led data collection on gender-based violence and other forms of interpersonal violence (EU-GBV) in the remaining countries. The use of a unified methodology will ensure the availability of comparable data across all EU Member States. Data collection will be completed this year, and the results will be used to update the domain of violence in the Gender Equality Index 2024, with its thematic focus on violence against women.

Description

Puuduvad tõendid, et hinnata naistevastast vägivalda

Eest punktisumma vägivalla valdkonnas puudub, sest puuduvad võrreldavad kogu ELi hõlmavad andmed.

Naiste tapmine

Vastavalt ametlikele teadetele mõrvati 2021. aastal 17 liikmesriigis lähisuhtepartneri, perekonnaliikme või sugulase poolt 720 naist. Eesti ei ole esitanud võrdlusandmeid tahtlike naisetapmiste kohta.

Allikas: Eurostat, 2021.

Vägivallast lühidalt

-

Lähisuhtevägivald

Eestis on 41% naistest, kes on kunagi olnud lähisuhtes, kogenud täiskasvanueas vägivalda lähisuhtepartneri poolt. Kokku 22% on kogenud füüsilist vägivalda (sh ähvardusi) või seksuaalset vägivalda ning 39% on kogenud psühholoogilist vägivalda. Ligikaudu 6% on kogenud lähisuhtevägivalda viimase 12 kuu jooksul ning 15% on seda kogenud viimase viie aasta jooksul.

Allikas: Eurostat, 2021.

-

Seksuaalne ahistamine töökohal

Eestis on umbes iga kolmas naine, kes on kunagi töötanud, kogenud seksuaalset ahistamist töökohal. Kuni 4% naistest on kogenud seksuaalset ahistamist tööl viimase 12 kuu jooksul ning 12% on kogenud seda viimase viie aasta jooksul.

Allikas: Eurostat, 2021.

Istanbuli konventsioon: hetkeseis

Istanbuli konventsioon on kõige terviklikum naistevastase vägivalla ja koduvägivalla ennetamise ja selle vastu võitlemise rahvusvaheline inimõiguste leping. Eesti allkirjastas Istanbuli konventsiooni 2014. aasta detsembris ja ratifitseeris selle 2017. aasta oktoobris. Leping jõustus Eestis 2018. aasta veebruaris.

Euroopa Ülemkogu kiitis ELi ühinemise Istanbuli konventsiooniga heaks 1. juunil 2023.

EIGE/FRA uuring naistevastase vägivalla kohta

Euroopa Liidu Põhiõiguste Amet (FRA) ja Euroopa Soolise Võrdõiguslikkuse Instituut (EIGE) korraldavad kaheksas ELi liikmesriigis (CZ, DE, IE, CY, LU, HU, RO, SE) naistevastase vägivalla uuringu (VAW II), mis täiendab ülejäänud riikides soolise vägivalla ja muude isikutevahelise vägivalla vormide andmete kogumist Eurostati juhtimisel. Ühtlustatud metoodika kasutamisega tagatakse kõigis ELi liikmesriikides võrreldavate andmete kättesaadavus. Andmete kogumine lõpeb sel aastal ja tulemustega ajakohastatakse 2024. aasta soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeksi vägivalla, eriti naistevastase vägivalla teemasuunda.

Thematic focus information

Description

In 2016, all women and men potential parents, aged 20-49, were eligible for parental leave in Estonia. In contrast to most of the EU countries, eligibility for parental leave is not constrained by employment status, duration or type of employment.

Same-sex parents are also eligible for parental leave in Estonia.

Description

In Estonia, 56 % of all informal carers of children are women. Overall, 53 % of women are involved in caring for or educating their children or grandchildren at least several times a week, compared to 56 % of men. Compared to the EU average (56 % of women and 50 % of men), slightly fewer women and slightly more men are involved in caring for or educating their children or grandchildren in Estonia. The gender gaps are wider among women and men who are working in the public sector (62 % and 48 %) and within the 50-64 age group (41 % and 29 %).

Estonia has reached only one of the Barcelona targets to have at least 33 % of children below the age of three and 90 % of children between the age of three and school age in childcare. About 27 % of children below the age of three are under some form of formal care arrangements, and 21 % of children this age are in formal childcare for at least 30 hours a week. Formal childcare is provided for 95 % of children from age three to the minimum compulsory school age (88 % are in formal childcare for at least 30 hours a week).

Around 9 % of households report unmet needs for formal childcare services. Lone mothers are only more slightly likely to report unmet needs for formal childcare services in Estonia (10 %), compared to couples with children (9 %).

Description

Most informal carers of older persons and/or persons with disabilities in Estonia are women (56 %). The shares of women and men involved in informal care of older persons and/or people with disabilities several days a week or every day are 12 % and 11 % respectively. The proportion of women involved in informal care is 3 p.p. lower than the EU average, while the involvement of men is 1 p.p. higher. Around 53 % of women carers of older persons and/or persons with disabilities are employed, compared to 43 % of men combining care with professional responsibilities.

In contrast, there are fewer women than men informal carers working in the EU. The gender gap is narrower in Estonia than in the EU (9 p.p. compared to 14 p.p. for the EU). In the 50-64 age group, 67 % of women and 26 % of men informal carers work, compared to the 20-49 age group, where 80 % of women and 92 % of men carers work. Around 15 % of women and 11 % of men in Estonia report unmet needs for professional home care services, which is the second lowest in the EU.

Description

In Estonia, women and men spend a similar amount of time commuting to and from work than (around 41 minutes per day for men and 43 minutes for women). There are minor differences between couples with and without children, however, men in couples without children travel around 8 minutes less than men in couples with children. Single people spend similar time commuting as people in couples do, with single men travelling around 48 minutes per day compared to 40 minutes per day for single women. Women spend more time commuting than men, regardless of whether they work part- or full-time. Women working part-time travel 40 minutes from home to work and back, and men commute 38 minutes, compared to 44 minutes for women and 41 minutes for men working full-time.

Generally, men are more likely to travel directly to and from work, whereas women make more multi-purpose trips, to fit in other activities such as school drop-offs or grocery shopping.

Description

Around 58 % of women and 59 % of men are unable to change their working time arrangements. Access to flexible working arrangements in Estonia is close to the EU average (57 % of women and 54 % of men). The private sector provides more flexibility over working time to both women and men (55 % and 58 % have no control over their working time arrangements), compared to the public sector, where women have less access to flexibility than men (66 % compared to 60 %).

Women are less likely to transition from part-time to fulltime work than men in the majority of EU countries, even though they are over-represented among part-time workers. In Estonia, 32 % of women and 42 % of men part-time workers transitioned to full-time work in 2017.

Description

Estonia is above the EU average in terms of participation rate in lifelong learning (17 %), with the fourth widest gender gap (6.9 p.p.). Women (aged 25-64) are more likely to participate in education and training than men regardless of their employment status. The highest difference is reported among unemployed women and men (9.7 p.p.) Conflicts with work schedules are a greater barrier to participation in lifelong learning for men (32 %) than for women (22 %). Family responsibilities are reported as barriers to engagement in education and training for 29 % of women compared to 12 % of men.

Both work schedules and family responsibilities are less of an obstacle for participation in lifelong learning in Estonia than in the EU overall. In the EU, 38 % of women and 43 % of men report their work schedule as an obstacle and 40 % of women and 24 % of men report that family responsibilities hinder participationin lifelong learning.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2020 focuses on digitalisation and the future of work. The thematic focus looks at three areas:

- use and development of digital skills and technologies

- digital transformation of the world of work

- broader consequences of digitalisation for human rights, violence against women and caring activities

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2021 focuses on gender inequalities in health. The thematic focus analyses the following aspects of health in the EU:

- health status and mental health

- heath behaviour

- access to health services

- sexual and reproductive health

- the COVID-19 pandemic.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2022 focuses on socio-economic consequences resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The thematic focus analyses the following aspects:

- Childcare

- Long-term care

- Housework

- Flexible working arrangement

The data was gathered using a survey that was carried out in all EU Member States between June and July 2021. Both the survey design and data collection timeframe ensured a comprehensive coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact. The survey was conducted using an international web panel with a quota sampling method based on a stratification approach[1]. It targeted the general population, aged between 20 and 64 years. Representative quotas were designed based on 2020 Eurostat population statistics. Post-stratification weighting was carried out to adjust for differences between the sample and population distribution in key variables and to ensure the sample accurately reflected the socio-demographic structure of the target population.

[1] The data was collected via a web survey using the international panel platform CINT as a main resource. CINT is an international platform that brings together several international panels, reaching more than 100 million registered panellists across more than 150 countries. To fulfil the required sampling in small countries, additional panel providers (IPSOS, TOLUNA, KANTAR) were engaged, which allowed for the same profiling requirements of the respondents and GDPR compliance.

Description

Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeks 2021 keskendub soolisele ebavõrdsusele tervise valdkonnas. Teemafookus analüüsib järgmisi terviseaspekte ELis:

- terviseseisund ja vaimne tervis;

- tervisekäitumine;

- terviseteenuste kättesaadavus;

- seksuaal- ja reproduktiivtervis;

- COVID-19 pandeemia.

Description

2022. aasta soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeks keskendub COVID-19 pandeemiast tulenevatele sotsiaal-majanduslikele tagajärgedele. Teemasuund analüüsib järgmisi aspekte:

- lapsehoid

- pikaajaline hooldus

- kodutööd

- paindliku töökorralduse muutumine

Andmed koguti küsitlusega, mis toimus kõigis ELi liikmesriikides 2021. aasta juunis ja juulis. Nii uuringu ülesehitus kui ka andmekogumise ajakava tagasid, et COVID-19 pandeemia mõju käsitleti põhjalikult. Uuring toimus rahvusvahelise veebipaneeli ja kihitamisel põhineva kvootvalimi meetodiga[1]. Uuringu sihtrühm oli 20–64-aastane üldelanikkond. Esinduslikud kvoodid koostati 2020. aasta Eurostati rahvastikustatistika põhjal. Kihitamisjärgsete kaaludega tasakaalustati peamiste muutujate erinevusi valimis ja elanikkonna jaotuses ning tagati, et valim kajastab täpselt sihtpopulatsiooni sotsiaal-demograafilist struktuuri.

[1] Andmeid koguti veebiküsitlusega, kasutades peamise vahendina rahvusvahelist paneeluuringu platvormi CINT. CINT on mitut rahvusvahelist paneeli koondav platvorm, millel on üle 100 miljoni registreeritud panelisti enam kui 150 riigist. Vajaliku valimi koostamiseks väikestes riikides kaasati täiendavad paneeluuringute ettevõtted (IPSOS, TOLUNA, KANTAR), mis võimaldasid kasutada vastajate jaoks samu profiilianalüüsi ja isikuandmete kaitse üldmääruse nõudeid.

Description

The Gender Equality Index 2023 focuses on the socially fair transition of the European Green Deal. Its thematic focus analyses the following aspects:

- Public attitudes and behaviours on climate change and mitigation

- Energy

- Transport

- Decision-making

The data was collected through various surveys, such as the EIGE 2022 survey on gender gaps in unpaid care, individual and social activities, as well as other EU-wide surveys.1 The EIGE survey focused on gender differences in unpaid care, including links to transport, the environment and personal consumption and behaviour.

[1] The following sources were used: the EIGE survey on gender gaps in unpaid care, individual and social activities; the European Social Survey; Eurostat-LFS; EU-SILC; education statistics; and the EIGE’s WiDM.

Description

Aruanne „Soolise võrdõiguslikkuse indeks 2023“ keskendub Euroopa rohelise kokkuleppe sotsiaalselt õiglasele üleminekule. Teemasuund analüüsib järgmisi aspekte:

- üldsuse hoiakud ja käitumisviisid seoses kliimamuutuste ja nende leevendamisega

- energia

- transport

- otsuste tegemine

Andmeid koguti mitmesuguste uuringute kaudu, nt EIGE 2022. aasta uuring soolise ebavõrdsuse kohta tasustamata hoolduse ning individuaalse ja ühiskondliku tegevuse valdkonnas, ning muud kogu ELi hõlmavad uuringud1. EIGE uuringus keskenduti soolistele erinevustele tasustamata hoolduse valdkonnas, sh seostele transpordi, keskkonna ning isikliku tarbimise ja käitumisega.

[1] Kasutati järgmisi allikaid: EIGE uuring soolise ebavõrdsuse kohta tasustamata hoolduse ning individuaalse ja ühiskondliku tegevuse valdkonnas; Euroopa sotsiaaluuring; Eurostati tööjõu-uuring; sissetulekuid ja elamistingimusi käsitlev ELi statistika; haridusstatistika ja EIGE statistika meeste ja naiste osakaalust otsuste tegemisel.